1453

Multimodal MR imaging approach to evaluate the interaction between cardiac pulsation and perivascular CSF motion1Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, United States, 2School of Medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Neurofluids

We designed a non-invasive multimodal MRI approach to evaluate the relationship between cardiac pulsation and perivascular cerebrospinal fluid (pCSF) dynamics in humans. We utilized cardiac-aligned resting-state functional MRI and dynamic diffusion-weighted imaging to describe cerebral vascular events and pCSF motion, respectively. This approach revealed that changes in cerebral blood volume preceded an increase in pCSF motion, demonstrating the cardiac cycle’s effect on pCSF dynamics. Our results parallel preclinical two-photon imaging findings of perivascular CSF dynamics in mice. Our in-vivo assessment of cardiac pulsations influencing pCSF motion provides a non-invasive look into a crucial part of the human brain’s glymphatic system.

Introduction

The glymphatic system is a proposed framework describing the pathway of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within the perivascular network of the brain1. The proper flow of CSF throughout the glymphatic system is essential for the delivery of nutrients2 and the removal of waste products3. Unlike how the heart propels blood throughout the systemic circulation, CSF does not have a designated propelling motor, and the complex mechanism behind CSF flow is not fully understood. Various studies have demonstrated that the driving forces of CSF flow include cardiac pulsation4–8, respiration9,10, and low-frequency oscillations9,11. Mestre et. al have demonstrated the cardiac pulsation influence on perivascular CSF (pCSF) flow in a murine model, finding that the peak arterial wall velocity corresponds well with the peak in CSF velocity4. However, a non-invasive evaluation of this phenomenon in humans remains limited with current imaging technologies.Methods

Image Acquisition:Both arterial blood flow and pCSF periodically oscillate with heartbeats. In our study, we applied cardiac-aligned resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) to represent pulsatile changes in cerebral blood volume (CBV) in major arteries and cardiac-aligned dynamic diffusion-weighted imaging (dDWI) to represent pCSF dynamics12. Rs-fMRI and dDWI sequences were run sequentially with the following acquisition parameters:

rs-fMRI: TR/TE = 375/31 msec, voxel size = 2.5 x 2.5 x 2.5 mm3, multiband acceleration = 8, 500 volumes, acquisition time of 188 seconds.

dDWI: TR/TE = 1999/48.6 msec, voxel size = 1.8 x 1.8 x 4 mm3, with three cardinal diffusion encoding directions (x/y/z) repeated 50 times, acquisition time of 340 seconds.

Data-driven masking:

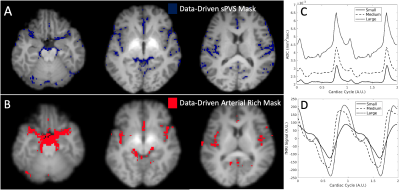

Data-driven masks were created in rs-fMRI to define arterial-rich regions and in dDWI spaces to define pCSF regions, as shown in Figure 1. We stratified our analysis by vessel size, using a vessel atlas created by Mouches and Forkert13. We defined the vessel radius size in millimeters (mm):

\[Small:0.3≤radius<0.6, Medium:0.6≤radius<0.9, Large:0.9≤radius<1.5\]

Image Processing:

In rs-fMRI, the signal minimum corresponds to the peak in finger plethysmography5,14. This represents the time when the arterial diameter peaks, which corresponds to the point in time of the largest CBV. In arteries, the change in signal throughout the cardiac cycle is related to the increase in CBV that occurs in the event of arterial pulsation. In our analysis, we inverted the fMRI signal so that the correlations between the peaks in the fMRI signal would positively correlate with the peaks in the dDWI signal. We also took the derivative of the fMRI signal [\(\frac{d}{dt}\)(fMRI)] to represent the changes in CBV with time.

Correlation Analysis:

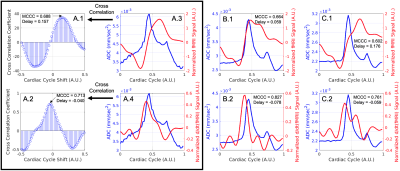

Following the extraction of dDWI and fMRI signals based on vessel radius size, the cross-correlation (MATLAB xcorr) between the demeaned dDWI and fMRI signals, as well as dDWI and signals were computed. The maximum cross-correlation coefficient (MCCC) and the corresponding delays were calculated for each scan and stratified by vessel size. The reported delay values were normalized as the ratio of a full cardiac cycle.

Reproducibility:

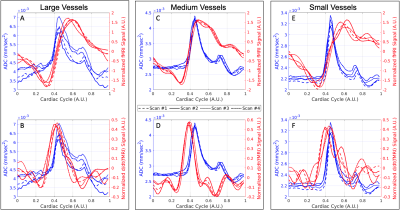

Repeated imaging studies were completed on two individuals (35 y/o, male – 4 scans, 19 y/o, female – 3 scans). The pCSF and fMRI waveforms were independently extracted and visually inspected for their reproducibility.

Results

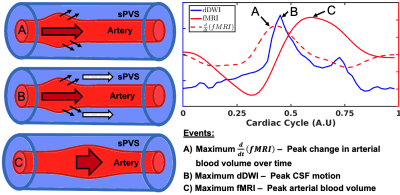

Our proposed model of arterial pulsation-driven CSF flow is described in Figure 2, where the peak \(\frac{d}{dt}\)(fMRI) is followed by peaks in the dDWI and then the fMRI signal. The representative curves of rs-fMRI and dDWI aligned with the cardiac cycle with respect to vessel radius size are shown in Figure 1(C-D). The correlation analysis of a representative subject is shown in Figure 3; the coefficients between dDWI, fMRI, and \(\frac{d}{dt}\)(fMRI) were high (MCCC>0.6) for all vessel sizes. The fMRI signal lags the dDWI signal, where the \(\frac{d}{dt}\)(fMRI) signal leads the dDWI signal. This order of events was consistently observed in the reproducibility tests (Figure 4). Two subjects have completed multiple scans, the delay values of their correlation analysis are summarized in Figure 5.Discussion

The events of the pCSF, fMRI, and \(\frac{d}{dt}\)(fMRI) waveforms have potential surrogate meanings, where surrogate measures of the physiological phenomenon throughout the cardiac cycle include (A) maximum \(\frac{d}{dt}\)(fMRI) which represents the peak change in CBV, (B) maximum dDWI which represents the maximum pCSF flow velocity, and (C) maximum fMRI represents maximum CBV. Our results closely align with preclinical findings measured using two-photon imaging by Mestre et al.4. They observed that maximum vessel wall velocities occur first, followed by the maximum pCSF flow velocity, and then maximum vessel wall diameter (Figure 3 in Mestre et al.4). We non-invasively reproduced this chain of events in the human brain through multimodal fMRI and dDWI, providing an in-vivo look at the relationship between perivascular CSF flow and cardiac pulsation.Conclusion

Our results highlight the value of rs-fMRI and dDWI in assessing the interaction between cardiac pulsation and surrounding pCSF dynamics, providing a non-invasive look into a crucial part of the brain’s glymphatic system. With a clinically feasible acquisition time for both imaging techniques, this method can be translated to study pathological conditions with known vascular impacts, such as stroke. Our approach could provide insight into pathology-dependent alterations of pCSF flow, which with further investigation, could help explain the etiology and course of neurodegenerative diseases.Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, R21AG068962 (PI: Yunjie Tong).References

- Iliff, J. J. et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci Transl Med 4, (2012).

- Jessen, N. A., Munk, A. S. F., Lundgaard, I. & Nedergaard, M. The Glymphatic System: A Beginner’s Guide. Neurochem Res 40, (2015).

- Nedergaard, M. Garbage truck of the brain. Science vol. 340 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1240514 (2013).

- Mestre, H. et al. Flow of cerebrospinal fluid is driven by arterial pulsations and is reduced in hypertension. Nat Commun 9, (2018).

- Rajna, Z. et al. Cardiovascular brain impulses in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 144, (2021).

- Kiviniemi, V. et al. Ultra-fast magnetic resonance encephalography of physiological brain activity-Glymphatic pulsation mechanisms? Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 36, (2016).

- Bilston, L. E., Fletcher, D. F., Brodbelt, A. R. & Stoodley, M. A. Arterial Pulsation-driven Cerebrospinal Fluid Flow in the Perivascular Space: A Computational Model. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 6, 235–241 (2003).

- Kedarasetti, R. T., Drew, P. J. & Costanzo, F. Arterial pulsations drive oscillatory flow of CSF but not directional pumping. Sci Rep 10, 10102 (2020).

- Vijayakrishnan Nair, V. et al. Human CSF movement influenced by vascular low frequency oscillations and respiration. Front Physiol 13, (2022).

- Klose, U., Strik, C., Kiefer, C. & Grodd, W. Detection of a relation between respiration and CSF pulsation with an echoplanar technique. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 11, 438–444 (2000).

- Yang, H.-C. (Shawn) et al. Coupling between cerebrovascular oscillations and CSF flow fluctuations during wakefulness: An fMRI study. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 42, 1091–1103 (2022).

- Wen, Q. et al. Assessing pulsatile waveforms of paravascular cerebrospinal fluid dynamics within the glymphatic pathways using dynamic diffusion-weighted imaging (dDWI). Neuroimage 260, 119464 (2022).

- Mouches, P. & Forkert, N. D. A statistical atlas of cerebral arteries generated using multi-center MRA datasets from healthy subjects. Sci Data 6, 29 (2019).

- Hermes, D., Wu, H., Kerr, A. B. & Wandell, B. A. Measuring brain beats: Cardiac‐aligned fast functional magnetic resonance imaging signals. Hum Brain Mapp (2022) doi:10.1002/hbm.26128.

Figures

Figure 2: Proposed model of perivascular (sPVS) cerebrospinal fluid flow (CSF) coupling to arterial pulsation with relation to cardiac-aligned dDWI and fMRI scans. Dynamic MRI curves are aligned to a single cardiac cycle where dDWI (solid blue), fMRI (solid red), and \(\frac{d}{dt}\)(fMRI) (dashed red) represent surrogate measures of perivascular CSF motion, cerebral blood volume (CBV), and the change in CBV over time, respectively. Events are described with respect to a traveling arterial pulsation throughout the perivascular space in vessels A to C.

Figure 3: Coupling of fMRI to dDWI and \(\frac{d}{dt}\)(fMRI) to dDWI. The top plots are depicting fMRI signal and dDWI signal and the bottom plots are displaying \(\frac{d}{dt}\)(fMRI) and dDWI signal aligned to a single cardiac cycle. (A.1-2) Displays the maximum correlation analysis between curves, where a positive delay means the fMRI signal lags the dDWI and a negative delay means the fMRI signal leads dDWI. Plots are stratified by vessel radius size of large (A), medium (B), and small (C) from left to right respectively.