1452

Do adult patients with moyamoya disease have glymphatic system dysfunction? - evaluation using diffusion along perivascular space1Neurosurgery, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan, 2Radiology, Juntendo University, Tokyo, Japan, 3Research Team of Neuroimaging, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology, Tokyo, Japan, 4Research Team for Neuroimaging, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology, Tokyo, Japan, 5Innovative Biomedical Visualization, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan, 6Radiology, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, glymphatic system

We aimed to evaluate the glymphatic system of adult moyamoya disease (MMD) by measuring diffusion along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS index). We evaluated 46 patients using diffusion MRI, perfusion parameters of 15O-gas PET, and cognitive tests, and 34 age-sex-matched normal controls. Compared to normal controls, patients with MMD showed significantly lower DTI-ALPS index. DTI-ALPS index in MMD revealed the correlation between perfusion and freewater parameters, and executive dysfunction, and suggested that dysfunction of the glymphatic system may exist, correlate with the degree of hemodynamic disturbance, lead to increased parenchymal free water, and relate to cognitive dysfunction in adult MMD.Background and Purpose

Moyamoya disease is a disease causing progressive stenosis of the intracranial arteries. Previous studies evaluating microstructural changes in this disease revealed decreased neurites, disrupted network complexity, and increased freewater1. Although decreased neurites and disrupted network complexity were within expectations from animal studies of chronic ischemic models, why parenchymal freewater increased in moyamoya disease, remains unclear.Recently, glymphatic system dysfunction emerged as a potential cause of increased parenchymal freewater via the deposition of parenchymal solutes in neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease2. Because the glymphatic system is regarded to use arterial pulsation as a driving force3, arterial stenosis in moyamoya disease may result in glymphatic system dysfunction.

This study aimed to evaluate whether glymphatic system dysfunction exists in moyamoya disease using diffusion MRI, and evaluate the relationship between glymphatic system activity and cerebral perfusion, parenchymal freewater, and cognitive function.

Materials and Methods

The ethical committees of local institutes approved this study protocol and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.Participants

Between 2015-2021, 46 patients (33 females; 38.4±1.9 years; 9 postoperative) participated in this study. All patients underwent an MRI scan and a cognitive test within 0–20 days (7 days on average). Twently-three (50%) patients without previous surgery received perfusion studies using 15O-gas positron emission tomography (PET) to confirm surgical indication. During the same period, 34 age-sex-matched normal controls (27 females; 38.4±2.2 years) were also evaluated with the same MRI protocol.

MRI acquisition

MRI data were acquired using a 3 T scanner (MAGNEOM Skyra, Siemens, Germany) equipped with a 32 multichannel receiver head coil. Diffusion-weighted images were acquired using a fat-saturated single-shot echo planar imaging sequence (b values and axes=0, 700: 30 axes, 2850: 60 axes), and the reversed-phase image was also acquired and used to estimate the susceptibility-induced off-resonance field to correct the deformation. Three-dimensional T1-weighted images (T1WI) were also obtained by rapid acquisition with a gradient echo sequence.

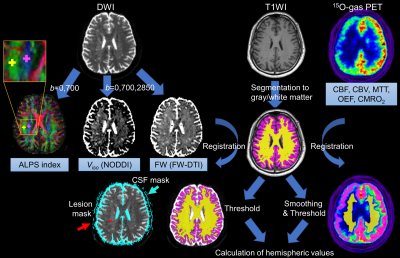

Calculation of the ALPS index

The single shell data (b = 0 and 700) was fit to the DTI model using FMRIB Software Library version 5.0.9, and 5-mm-diameter region-of-interests were manually placed in the projection and association fiber of the level of the lateral ventricles on each subject’s color-coded fractional anisotropy map using ITK-SNAP (http://www.itksnap.org/, Fig. 1). ALPS index of each hemisphere was calculated using the x-axis- and the y-axis-diffusivity in the projection area (Dxxproj and Dyyproj), and the x-axis- and the z-axis-diffusivity in the association area (Dxxassoc and Dzzassoc)4:

$$ALPS index = (Dxxproj+Dxxassoc)/(Dyyproj+Dzzassoc) $$

Generation of freewater parametric maps

The multi-shell data was fitted to the NODDI model5 using the Accelerated Microstructure Imaging via Convex Optimization (https://github.com/daducci/AMICO) to produce isotropic volume fraction (Viso), and also to a regularized bi-tensor model6 by the in-house script to create free water fraction (FW) of each participant.

Evaluating perfusion and cognitive performance

PET was acquired using a Discovery 710 PET/CT scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, U.S.A.). By sequential inhalation and scan of C15O2, 15O2, and C15O, the parametric maps including cerebral blood flow (CBF) and cerebral blood volume (CBV) were generated7. Mean transit time (MTT) maps were created by calculating the CBV/CBF values on a voxel-by-voxel basis.

All patients were evaluated with Trail Making Test parts A and B (TMT-A and B) which assess the speed of information processing and executive functioning, respectively. TMT-A and -B results were normalized using the age-specific average value of the healthy controls8.

Calculation of Regional values and statistical analysis

After the removal of extracellular signals from each map of perfusion and freewater, hemispheric values of the normal-appearing cortex and white matter were calculated using region-of-interests created from segmented T1WI1. Comparison between the ALPS index of patients and controls, and correlation analysis between the ALPS index and perfusion parameters, freewater parameters, and cognitive performance were performed using unpaired T test and Pearson correlation coefficients. P<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

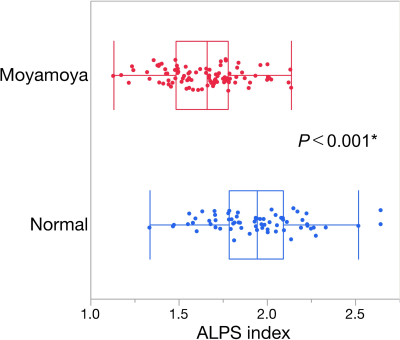

Compared to normal controls, patients with moyamoya disease showed a significant decrease in the ALPS index (Fig. 2).By correlation analysis with perfusion parameters, the ALPS index showed a significant negative correlation between MTT (Fig. 3).

ALPS index of the patients showed a significant negative correlation between Viso and FW, while no correlation was observed between those of normal controls (Fig. 4).

ALPS index of the left hemisphere revealed a significant correlation between executive dysfunction (TMT-B, Fig. 5).

Discussion

ALPS index indicates the ratio of diffusivity in the direction of the perivascular space, thus this index may reflect the function of the glymphatic system. The lower ALPS index in moyamoya disease suggested glymphatic system dysfunction, as in our hypothesis. The negative correlation between ALPS index and MTT, the reciprocal index of cerebral perfusion pressure, as well as Viso/FW, suggested that decreased cerebral perfusion pressure may induce glymphatic system dysfunction and increase parenchymal freewater. However, the correlation was weak, so some other factors such as blood-brain barrier dysfunction9 may also relate to the changes in ALPS index and free water. The correlation between ALPS index and executive dysfunction was moderate but was not as strong as the correlation observed in neurite parameters1. Structural damage may have a stronger effect on cognitive function than glymphatic system dysfunction in this disease population.Acknowledgements

We thank the Department of Radiology in Tokyo Medical Clinic for magnetic resonance imaging acquisition. This work was partly supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research “KAKENHI,” the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant nos. JP16H06280, JP18H02772, 19K17244, 19K18406 and 20K16737).References

1. Hara S, Hori M, Ueda R, et al. Unraveling Specific Brain Microstructural Damage in Moyamoya Disease Using Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Positron Emission Tomography. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases 2019;28:1113-1125

2. Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:147ra111

3. Iliff JJ, Wang M, Zeppenfeld DM, et al. Cerebral arterial pulsation drives paravascular CSF-interstitial fluid exchange in the murine brain. J Neurosci 2013;33:18190-18199

4. Taoka T, Masutani Y, Kawai H, et al. Evaluation of glymphatic system activity with the diffusion MR technique: diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) in Alzheimer's disease cases. Japanese journal of radiology 2017;35:172-178

5. Zhang H, Schneider T, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, et al. NODDI: practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain. Neuroimage 2012;61:1000-1016

6. Pasternak O, Sochen N, Gur Y, et al. Free water elimination and mapping from diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med 2009;62:717-730

7. Hara S, Tanaka Y, Inaji M, et al. Spatial coefficient of variation of arterial spin labeling MRI for detecting hemodynamic disturbances measured with (15)O-gas PET in patients with moyamoya disease. Neuroradiology 2022;64:675-684

8. Toyokura M, Tanaka H, Furukawa T, et al. Normal Aging Effect on Cognitive Task Performance of Information-processing Speeed: Analysis of Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task and Trail Making Test. Brain Science and Mental Disorders 1996;7:401-409

9. Narducci A, Yasuyuki K, Onken J, et al. In vivo demonstration of blood-brain barrier impairment in Moyamoya disease. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2019;161:371-378

Figures