1446

Lower-limb walking kinetics associated with acetabular and femoral bone remodeling in hip OA: a PET-MR study

Koren Roach1,2, Radhika Tibrewala2,3, Valentina Pedoia2, Emma Bahroos2, Sharmila Majumdar2, and Richard Souza2

1University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States, 3New York University, New York, NY, United States

1University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States, 3New York University, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, MSK

Early hip osteoarthritis is clinically hypothesized to include alterations in joint motion and bone remodeling. This study investigated the relationships between lower-limb joint kinetics and bone remodeling, measured via positron emission tomography. Our results suggest that greater hip flexion and internal rotation loading and more uniform knee abduction loading are associated with bone remodeling and may serve as early biomechanical biomarkers for hip OA.Introduction

Hip osteoarthritis (OA) is a common cause of disability and results from an imbalance between tissue repair and destruction within the joint, primarily driven by mechanical factors1. Altered joint loading patterns cause regions of chronic overload or underload, resulting in increased or insufficient cartilage stresses. These altered cartilage stresses cause changes to the structure and composition of the articular cartilage, which coincide with or precede the development of hip OA2,3. Altered joint loads can affect bone shape, which has also been correlated with OA4, through bone remodeling, which can be measured using standardized uptake values (SUV) of sodium fluoride radiotracer [18F]-NaF during positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. Although joint loads can be evaluated through motion analysis and biomechanics, it is unclear how biomechanics are related to bone remodeling and SUV in early hip OA development. The aim of this work was to assess relationships between lower-limb joint biomechanics and bone remodeling in participants with early-to-moderate hip OA.Methods

Sixteen subjects (8 female; age: 56.0±16.4 years; BMI: 24.5±3.4 kg/m2) with hip Kellgren-Lawrence scores of 0-3 were recruited and signed informed consent as approved by the Committee of Human Research at our institution. PET-MR scans were acquired of each participant on a SIGNA 3T time of flight PET-MR scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) with a timing resolution <400 ps and a flex coil positioned around one hip. Participants received an intravenous catheter and were positioned feet first and supine within the scanner. [18F]-NaF was produced at the University of California, San Francisco cyclotron facility under current good manufacturing practices and used as a tracer during this study. Dixon fat-water and 3D sagittally combined T1ρ/T2 Magnetization-Prepared Angle-Modulated Partitioned k-Space Spoiled Gradient Echo Snapshots (MAPSS) sequences of bilateral hips were acquired simultaneously with the 45-minute dynamic PET scan5. An MR-based attenuation correction of PET photons was performed using the Dixon fat-water sequence. PET reconstructions employed a 3D ordered-subset expectation maximization. The axially acquired static PET images were resampled into the sagittal plane, non-rigidly registered to the MAPSS images, and, with the participant’s weight and injected tracer dose, used to construct SUV maps. The acetabulum and femur were segmented on the MAPSS images to determine maximum and mean standardized uptake values (SUVs) for each bone. Each participant also completed biomechanics testing at the UCSF Human Performance Center. Skin marker trajectory data was acquired with a 10 camera near-infrared system (Vicon, Oxford Metrics LTD.) at 250 Hz while ground reaction forces (GRFs) were simultaneously acquired from two in-ground force plates (Advanced Mechanical Technology Inc.) at 1000 Hz. Skin markers were applied to the trunk and lower limbs of each subject prior to data collection. Subjects completed five walking trials. Trajectory and GRF data were filtered and used to calculate time-normalized hip, knee, and ankle internal joint moments during stance (Visual3D, C-Motion). Multivariate functional principal component analysis (MFPCA) was performed for each activity on the combined sagittal, coronal, and transverse plane kinetics for each joint. Pearson correlations were used to assess relationships between the first five MFPC scores and SUV in the acetabulum and femur (R Core Team, 2020, version 4.0.3). Significance was set at p < 0.05.Results

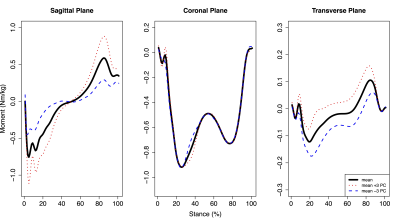

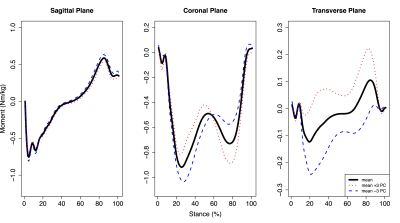

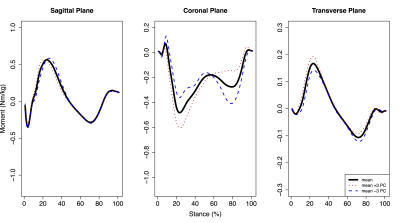

For hip moments, PC3 (9.7% of variation) was significantly positively correlated with mean femoral (r=0.401, p=0.042) and maximum acetabular (r=0.476, p=0.014) and femoral (r=0.503, p=0.009) SUV, while PC4 (5.3% of variation) was significantly positively correlated with mean acetabular (r=0.498, p=0.010) and femoral (r=0.527, p=0.006) SUV. Hip PC3 (Fig. 1) was primarily characterized by differences in flexion/extension moment amplitudes and magnitude shifts in transverse plane moments. Hip PC4 (Fig. 2) was primarily characterized by magnitude shifts in ab/adduction moments and differences in transverse moment slopes during early midstance and unloading. For knee moments, PC5 (2.9% of variation) was significantly negatively correlated with mean and maximum acetabular (mean: r=-0.479, p=0.013; maximum: r=-0.471, p=0.015) and femoral (mean: r=-0.473, p=0.015; maximum: r=-0.415, p=0.035) SUV. Knee PC5 (Fig. 3) was primarily characterized by magnitude differences in the abduction moment peaks and the first peak adduction moment.Discussion

Participants with a greater range of hip flexion moments, greater hip internal rotation moments, greater peak knee adduction, and more uniform knee adduction peaks exhibited higher SUV. Participants with greater peak hip flexion and extension moments may exert greater loads across the hip joint, which could cause bone remodeling and explain the higher SUV for these participants. Greater hip internal rotation moments may initiate greater gluteus medius and gluteus minimus activation, which exhibited significant atrophy, decreased muscle volume, and increased fatty infiltration in those with late-stage hip OA6-8 and suggests that higher SUV is an indicator of early-stage hip degeneration that occurs prior to hip muscle weakness. Participants that exhibited greater peak knee adduction moments, which were associated with contralateral end-stage hip OA9, had higher SUV, suggesting increased peak knee adduction as an early and late hip OA biomarker. Future work will explore how these results relate to quantitative measures of hip cartilage health.Conclusion

In participants with early-to-moderate hip OA, greater hip loads and more uniform peak knee abduction moments may be early indicators of bone remodeling and disease development or progression.Acknowledgements

Funding is gratefully acknowledged from the National Institutes of Health: K24 AR072133, R01 AR069006, R00AR070902.References

- K. D. Brandt, P. Dieppe, and E. Radin, Etiopathogenesis of osteoarthritis, Med Clin North Am, 2009, 93(1), 1-24, xv.

- M. C. Gallo, C. Wyatt, V. Pedoia, D. Kumar, S. Lee, L. Nardo, T. M. Link, R. B. Souza, and S. Majumdar, T1rho and T2 relaxation times are associated with progression of hip osteoarthritis, Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2016, 24(8), 1399-1407.

- C. Wyatt, D. Kumar, K. Subburaj, S. Lee, L. Nardo, D. Narayanan, D. Lansdown, T. Vail, T. M. Link, R. B. Souza, and S. Majumdar, Cartilage T1rho and T2 Relaxation Times in Patients With Mild-to-Moderate Radiographic Hip Osteoarthritis, Arthritis Rheum, 2015, 67(6), 1548-1556.

- M. A. Bowes, K. Kacena, O. A. Alabas, A. D. Brett, B. Dube, N Bodick, and P. G. Conaghan, Machine-learning, MRI bone shape and important clinical outcomes in osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative, Ann Rheum Dis, 2021, 80(4), 502-508.

- R. Tibrewala, E. Bahroos, H. Mehrabian, S. C. Foreman, T. M. Link, V. Pedoia, and S. Majumdar, [18 F]-Sodium Fluoride PET/MR Imaging for Bone-Cartilage Interactions in Hip Osteoarthritis: A Feasibility Study, J Orthop Res, 2019, 37(12), 2671-2680.

- F. Dobson, R. S. Hinman, M. Hall, C. B. Terwee, E. M. Roos, and K. L. Bennell, Measurement properties of performance-based measures to assess physical function in hip and knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review, Osteoarthr Cartil, 2012, 20, 1548-1562.A. Zacharias, T. Pizzari, D. J. English, T. Kapakoulakis, and R. A. Green, Hip abductor muscle volume in hip osteoarthritis and matched controls, Osteoarthr Cartil, 2016, 24, 1727-1735.

- R. Tibrewala, V. Pedoia, J. Lee, C. Kinnunen, T. Popovic, A. L. Zhang, T. M. Link, R. B. Souza, and S. Majumdar, Automatic hip abductor muscle fat fraction estimation and association with early OA cartilage degeneration biomarkers. J Orthop Res, 2020, 39, 2376-2387.

- N. Shakoor, D. E. Hurwitz, J. A. Block, S. Shott, and J. P. Case, Asymmetric knee loading in advanced unilateral hip osteoarthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 2003, 48, 1556-1561.

Figures

Figure 1: Mean hip moments plus or minus three standard deviations of hip moment principal component (PC) 3 during the stance phase of walking. Hip moment PC3 accounted for 9.7% of variation in the population and was significantly positively correlated with mean femoral and maximum acetabular and femoral SUV. Flexion, adduction, and internal rotation moments were positive.

Figure 2: Mean hip moments plus or minus three standard deviations of hip moment principal component (PC) 4 during the stance phase of walking. Hip moment PC4 accounted for 5.3% of variation across participants and was significantly positively correlated with mean acetabular and femoral SUV. Flexion, adduction, and internal rotation moments were positive.

Figure 3: Mean knee moments plus or minus three standard deviations of knee moment principal component (PC) 5 during the stance phase of walking. Knee moment PC5 accounted for 2.9% of variation across participants and was significantly negatively correlated with mean and maximum acetabular and femoral SUV. Flexion, adduction, and internal rotation moments were positive.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1446