1443

Inspiratory dilatory tongue movement, as measured with tagged MRI, and intramuscular neural drive in obstructive sleep apnoea patients1Neuroscience Research Australia, Sydney, Australia, 2University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, 3Macquarie Medical School, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia, 4Prince of Wales Hospital, Sydney, Australia, 5Flinders Health and Medical Research Institute, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia

Synopsis

Keywords: Muscle, Muscle, electromyography, sleep, tagged MRI

As measured by tagged MRI, inspiratory tongue dilatory movement might be useful to shed new light on mechanisms controlling upper airway dilation in obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA). Nine healthy controls and 37 untreated OSA patients underwent an upper airway MRI scan and tongue intramuscular electromyography (EMG) assessment. Results identified two opposing relationships between inspiratory tongue movement and phasic EMG with variable impacts on upper airway function for controls and OSA patients. These results suggest that there are complex, and unexpected, relationships between neural drive and anterior tongue movement that suggest upper airway function cannot be predicted from EMG alone.Background

Effective upper airway dynamic behaviour is critical to maintaining airway patency (1, 2). Failure to physiologically recruit and coordinate dilator muscles result in apnoeas and hypopnoeas during sleep, limiting airflow as in obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), a common sleep breathing disorder (at least 10-20% of adults (3)). There is considerable heterogeneity in underlying pathophysiology within the OSA population (4, 5), and it is only partially understood why some patients are unable to activate their upper airway dilator sufficiently (e.g. tongue muscles) to maintain airway patency during sleep (6). We have previously reported regional variation in tongue dilatory movement during inspiration, as measured by tagged MRI, in awake people with OSA (7). This is thought to reflect regional neural drive to the genioglossus, the largest dilatory muscle of the upper airway, but has not been comprehensively evaluated. Therefore, this study aims to examine the relationship between inspiratory tongue movement, as measured by tagged MRI, and intramuscular neural drive, as measured by electromyography (EMG), and to investigate how this relationship is related to OSA pathophysiology.Methods

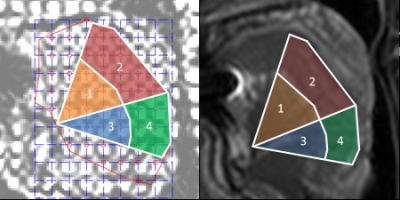

The study was approved by the South Eastern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/13/POWH/745). Forty-six participants (11 women, 20–73 years) underwent an MRI scan (Achieva 3TX, Philips). The severity of OSA was measured by the apnoea hypopnoea index (AHI), which is the number of apnoeas and hypopnoeas per hour of sleep. Nine participants had no OSA (AHI 2.8 ± 1.9 [0.5 – 5.0] events/hr sleep), and 37 had untreated OSA from mild to severe (28.5 ± 21.4 [5.6 - 94.3] events/hr sleep). Both groups were matched for age, BMI and gender proportion.Tagged MRI and intramuscular EMG measurements were obtained for the anterior and posterior regions of the horizontal and oblique tongue neuromuscular compartments during nasal breathing in the supine position awake (Figure 1). Mid-sagittal tagged MRI images were collected by superimposing a grid on the tissues using a spatial modulation of magnetisation sequence. Images were acquired every 250 ms during 30 seconds of nasal breathing (7). Imaging parameters: TR/TE = 400/16 ms, FOV = 220 × 196 mm, slice thickness = 10 mm, in-plane spatial resolution = 0.86 × 0.86 mm2, tag spacing = 8.6 mm. Anterior tongue movement was quantified using harmonic phase methods (8) and classified in four different dilatation patterns, as previously described in our previous work (7): 1, ‘en bloc’, where the amplitude of the anterior movement of both compartments was >1 mm; 2, ‘oropharyngeal’, where the amplitude of the anterior movement of the horizontal compartment was >1 mm and oblique compartment <1 mm; 3, ‘minimal’, where the amplitude of the anterior movement of both compartments was <1 mm; and 4, ‘bidirectional’, where the two posterior compartments moved in opposite directions. Genioglossus neural drive was measured as phasic and tonic EMG activity during inspiration and was normalised to a maximum voluntary contraction (tongue protrusion) over 54±33 [14-195] breaths.

Results

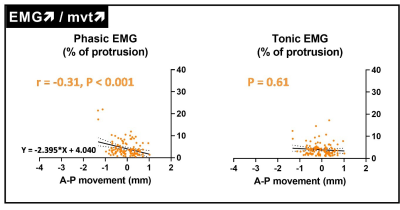

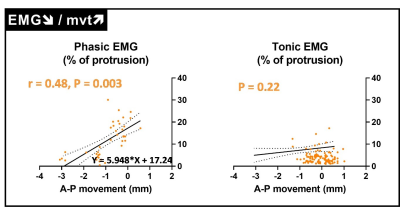

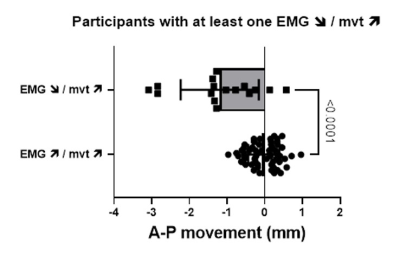

Tagged MRI and EMG measurements were obtained for 155 neuromuscular compartments out of 184 (i.e. 4 compartments for every 46 participants, 84%). As expected, for 116 neuromuscular tongue compartments (75%), a larger anterior movement was associated with a higher phasic EMG (namely EMG↗/mvt↗, Figure 2). In contrast, for the remaining 39 (25%) compartments, a larger anterior movement was associated with a smaller phasic EMG (namely EMG↘/mvt↗, Figure 3). No relationships between tongue movements and tonic EMG were observed.Twenty participants (42%) had at least one neuromuscular compartment with EMG↘/mvt↗. The proportion of OSA patients did not differ between participants with and without EMG↘/mvt↗ (90 vs 73%, Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.26). EMG↘/mvt↗ neuromuscular compartments were more commonly seen in the horizontal section of the tongue (71% and 61% for the posterior and anterior compartments vs 36% and 33% for the respective oblique compartments, Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.049).

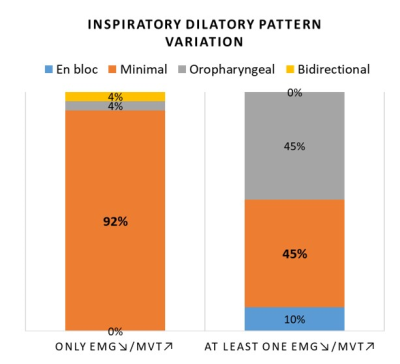

92% (24/26) of participants with only EMG↗/mvt↗ compartments achieved minimal dilatory movement patterns, and this one not the case for participants with at least one EMG↘/mvt↗ (Figure 4), for who larger anterior movement was achieved by the EMG↘/mvt↗ compartments for en bloc and oropharyngeal dilatory patterns (Figure 5).

Conclusions

These results suggest that there are complex, and in some cases, unexpected, relationships between neural drive and anterior tongue movement for ¼ of the neuromuscular tongue compartments, suggesting that dilatory tongue function cannot be predicted from EMG alone. Larger dilatory movement during inspiration reflected increased drive to genioglossus for ¾ of the neuromuscular compartments, and this was most commonly seen in the oblique compartments. Horizontal and oblique regions of the genioglossus are innervated by different branches of the hypoglossal nerve and may function independently. Understanding the mechanisms controlling upper airway dilation using tagged MRI offers a new avenue to understand OSA pathogenesis better.Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (#APP1058974). Lynne E. Bilston, S.C. Gandevia, D. Eckert, and J. Butler are supported by NHMRC Fellowships. The authors thank the NeuRA imaging centre for their technical support.References

1. Strohl KP, Butler JP, Malhotra A. Mechanical properties of the upper airway. Compr Physiol 2012; 2: 1853-1872.

2. Edwards BA, White DP. Control of the pharyngeal musculature during wakefulness and sleep: implications in normal controls and sleep apnea. Head Neck 2011; 33 Suppl 1: S37-45.

3. Lechat B, Naik G, Reynolds A, Aishah A, Scott H, Loffler KA, Vakulin A, Escourrou P, McEvoy RD, Adams RJ, Catcheside PG, Eckert DJ. Multinight Prevalence, Variability, and Diagnostic Misclassification of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022; 205: 563-569.

4. White DP. Pathogenesis of obstructive and central sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 172: 1363-1370.

5. Eckert DJ, White DP, Jordan AS, Malhotra A, Wellman A. Defining phenotypic causes of obstructive sleep apnea. Identification of novel therapeutic targets. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188: 996-1004.

6. Younes M. Role of respiratory control mechanisms in the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep disorders. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2008; 105: 1389-1405.

7. Juge L, Knapman FL, Burke PGR, Brown E, Bosquillon de Frescheville AF, Gandevia SC, Eckert DJ, Butler JE, Bilston LE. Regional respiratory movement of the tongue is coordinated during wakefulness and is larger in severe obstructive sleep apnoea. J Physiol 2020; 598: 581-597.

8. Osman NF, Kerwin WS, McVeigh ER, Prince JL. Cardiac motion tracking using CINE harmonic phase (HARP) magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 1999; 42: 1048-1060.

Figures