1442

Diagnostic performance of Rapid Whole-body MRI with uniformly fat-suppressed T2-weighted imaging for multiple myeloma

Rianne A van der Heijden1, Timothy M Schmidt2, Scott B Reeder1,3,4,5,6, and Ali Pirasteh1,3

1Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 2Carbone Cancer Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 3Department of Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 4Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 5Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 6Department of Emergency Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States

1Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 2Carbone Cancer Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 3Department of Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 4Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 5Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 6Department of Emergency Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Skeletal, PET/MR, Multiple Myeloma

In this study we evaluated the diagnostic performance of whole-body T2-weighted imaging with uniform 2-point Dixon fat-suppression for the detection of multiple myeloma. Furthermore, we evaluated the added sensitivity, change in disease stage, and change in treatment plan with the sequential addition of DWI and FDG PET. T2-Dixon demonstrated higher sensitivity than both DWI and PET. Adding DWI did not change stage or treatment plan. However, the addition of PET did change the treatment plan in one patient with extra-osseous disease. Whole-body PET-MRI with T2-Dixon is a promising and efficient tool for assessment of multiple myeloma.Introduction

Whole-body MRI is the most sensitive test for detection of multiple myeloma (MM) lesions1–5. Early detection of focal lesions is important to identify patients who should receive early treatment to prevent morbidity from symptomatic bone disease6. 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET is widely considered the reference imaging standard to assess treatment response in MM7. Therefore, a combined whole-body PET/MRI may be the most comprehensive imaging approach for MM.Whole-body (WB) diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) are often used to assess MM. However, DWI (especially wide field of view WB imaging) suffers from limitations, such as prolonged scan times, image distortion, incomplete bone marrow and subcutaneous fat suppression, and poor anatomic delineation, often leading to incomplete exams, non-diagnostic images, and inaccurate/imprecise ADC8–17. WB T2-weighted fast-spin-echo imaging with uniform Dixon-based fat-suppression (T2-Dixon) has shown promise to outperform DWI in detection of metastatic bone lesions18. Moreover, Dixon-based approach provides a more uniform fat-suppression than the spectral-fat-suppression techniques and also generates in- and opposed-phase (IP and OP) images that assist with lesion characterization based on fat content19,20. Hence, we evaluated the diagnostic performance of WB T2-Dixon for detection of MM lesions, and the incremental performance of DWI and PET to detect additional lesions, and the overall impact on patient management.

Methods

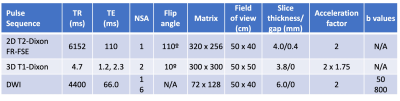

This IRB-approved retrospective study reviewed WB PET/MRI exams for MM between August 2019 and April 2022.Exams were performed on a PET/MRI scanner (Signa PET/MR, GE Healthcare), 60 minutes after FDG intravenous injection. Simultaneously, in each PET bed, the following MRI sequences were acquired (Table 1): T1-weighted two-point Dixon for MR-based attenuation correction, 3D T1-weighted gradient-echo with Dixon, and T2-weighed fast spin-echo with Dixon. Once all PET beds were completed from skull to feet, axial whole-body DWI was acquired.

Two readers (one fellowship trained radiologist/nuclear medicine physician and one musculoskeletal radiologist with PET/MRI experience) interpreted the studies in consensus per following: blinded to PET and DWI, T2-Dixon (water-only) images were reviewed alongside T1-Dixon (water-only) images. IP, OP, and fat-only images were also available to help with lesion characterization as needed, simulating real-life practice.

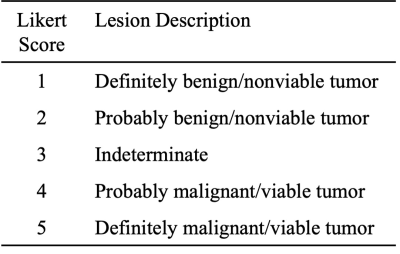

Disease extent was recorded for each of the following 8 body compartments: calvarium, scapulae/sternum, ribs, cervicothoracic spine, lumbosacral spine, pelvis, lower extremities, upper extremities, and extraosseous. For each compartment up to 3 focal lesions were recorded and evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale (Table 2). Lesions rated ≥3 were considered suspicious. Number of lesions per compartment (up to 5) were noted. Diffuse disease was also recorded, and any superimposed focal lesions were also recorded.

Exams were subsequently re-evaluated with the addition of DWI. The number and level of suspicion for lesions seen on DWI were recorded in a similar manner and subsequently on PET. Reference standard for lesion detection and characterization was consensus assessment utilizing all available PET/MRI images, prior/follow up imaging, clinical history, and histology.

In order to determine the impact of each sequence on patient management, a hematologist oncologist with subspecialty expertise in treatment of multiple myeloma reviewed the imaging results and all available clinical/imaging/histologic information to determine if a change in management would result based on adding information from DWI, PET, or both, compared to using only the information obtained by T1- and T2-weighted Dixon images. Sensitivity for T2, DWI, and PET were compared by McNemar test. P <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

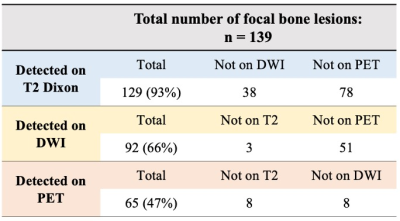

34 MM patients were reviewed (average age 67 years (range 34-83), 38% female). DWI was not obtained in 3 patients who requested exam termination due to discomfort and were excluded. In the remaining 31 patients, 139 focal lesions were identified per the reference standard. T2-Dixon had a significantly higher sensitivity than DWI and PET, respectively 93%, 66% and 47%, P<0.001 (Table 3). Adding DWI to T2-Dixon resulted in detection of 3 additional lesions, but this did not change disease stage or treatment strategy. Adding PET to T2-Dixon and DWI resulted in detection of 7 additional lesions and changed management by detecting an otherwise normal-appearing lymph node. There were 5 false positive lesions for T2-Dixon, 9 for DWI, and 2 for PET. Among 11 patients with diffuse bone marrow disease, T2-Dixon identified all cases, DWI identified 10/11 (91%) and PET only detected 6/11 (55%) (P=0.06).Discussion

Whole-body T2 with Dixon fat-suppression detected more lesions than DWI in the setting of MM; adding DWI did not impact disease stage or patient management. However, while PET demonstrated lower sensitivity than T2-Dixon in detection of focal and diffuse disease, it remains the best modality for follow-up and can identify extra-osseous disease. Hence, whole-body PET/MRI with T2-Dixon demonstrates promise as a rapid imaging modality in assessment of MM.Limitations of this study include its retrospective nature and small sample size. Another limitation was absence of independent evaluation of DWI and PET. However, our approach aimed to simulate real-life clinical practice to assess the incremental value in adding DWI and PET to detect lesions in addition to WB T2.

Conclusion

Whole-body PET-MRI with T2-Dixon is a promising and efficient tool for the assessment of multiple myeloma; the addition of DWI did not impact disease detection or staging and did not impact patient management.Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge support from GE Healthcare and Bracco Diagnostics who provide research support to the University of Wisconsin. Dr. Reeder is the Fred Lee Sr. Endowed Chair of Radiology.References

1. Cascini GL, Falcone C, Console D, Restuccia A, Rossi M, Parlati A, et al. Whole-body MRI and PET/CT in multiple myeloma patients during staging and after treatment: personal experience in a longitudinal study. Radiol Med (Torino). 2013 Sep;118(6):930–48.2. Shortt CP, Gleeson TG, Breen KA, McHugh J, O’Connell MJ, O’Gorman PJ, et al. Whole-Body MRI Versus PET in Assessment of Multiple Myeloma Disease Activity. Am J Roentgenol. 2009 Apr;192(4):980–6.

3. Pawlyn C, Fowkes L, Otero S, Jones JR, Boyd KD, Davies FE, et al. Whole-body diffusion-weighted MRI: a new gold standard for assessing disease burden in patients with multiple myeloma? Leukemia. 2016 Jun;30(6):1446–8.

4. Zamagni E, Nanni C, Patriarca F, Englaro E, Castellucci P, Geatti O, et al. A prospective comparison of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and whole-body planar radiographs in the assessment of bone disease in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2007 Jan 1;92(1):50–5.

5. Dimopoulos MA, Hillengass J, Usmani S, Zamagni E, Lentzsch S, Davies FE, et al. Role of magnetic resonance imaging in the management of patients with multiple myeloma: a consensus statement. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2015 Feb 20;33(6):657–64.

6. Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Blade J, Merlini G, Mateos MV, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014 Nov;15(12):e538–48.

7. Cavo M, Terpos E, Nanni C, Moreau P, Lentzsch S, Zweegman S, et al. Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis and management of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell disorders: a consensus statement by the International Myeloma Working Group. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Apr;18(4):e206–17.

8. Moreau B, Iannessi A, Hoog C, Beaumont H. How reliable are ADC measurements? A phantom and clinical study of cervical lymph nodes. Eur Radiol. 2018 Aug;28(8):3362–71.

9. Murphy P, Wolfson T, Gamst A, Sirlin C, Bydder M. Error model for reduction of cardiac and respiratory motion effects in quantitative liver DW-MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2013 Nov;70(5):1460–9.

10. Benner T, van der Kouwe AJW, Sorensen AG. Diffusion imaging with prospective motion correction and reacquisition. Magn Reson Med. 2011 Jul;66(1):154–67.

11. Gumus K, Keating B, Poser BA, Armstrong B, Chang L, Maclaren J, et al. Prevention of motion-induced signal loss in diffusion-weighted echo-planar imaging by dynamic restoration of gradient moments. Magn Reson Med. 2014 Jun;71(6):2006–13.

12. Lewis S, Dyvorne H, Cui Y, Taouli B. Diffusion-weighted imaging of the liver: techniques and applications. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2014 Aug;22(3):373–95.

13. Miquel ME, Scott AD, Macdougall ND, Boubertakh R, Bharwani N, Rockall AG. In vitro and in vivo repeatability of abdominal diffusion-weighted MRI. Br J Radiol. 2012 Nov;85(1019):1507–12.

14. Chen X, Qin L, Pan D, Huang Y, Yan L, Wang G, et al. Liver diffusion-weighted MR imaging: reproducibility comparison of ADC measurements obtained with multiple breath-hold, free-breathing, respiratory-triggered, and navigator-triggered techniques. Radiology. 2014 Apr;271(1):113–25.

15. Michoux NF, Ceranka JW, Vandemeulebroucke J, Peeters F, Lu P, Absil J, et al. Repeatability and reproducibility of ADC measurements: a prospective multicenter whole-body-MRI study. Eur Radiol. 2021 Jul;31(7):4514–27.

16. Liau J, Lee J, Schroeder ME, Sirlin CB, Bydder M. Cardiac motion in diffusion-weighted MRI of the liver: artifact and a method of correction. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2012 Feb;35(2):318–27.

17. Nasu K, Kuroki Y, Sekiguchi R, Nawano S. The effect of simultaneous use of respiratory triggering in diffusion-weighted imaging of the liver. Magn Reson Med Sci MRMS Off J Jpn Soc Magn Reson Med. 2006 Oct;5(3):129–36.

18. Wang X, Pirasteh A, Brugarolas J, Rofsky NM, Lenkinski RE, Pedrosa I, et al. Whole-body MRI for metastatic cancer detection using T 2 -weighted imaging with fat and fluid suppression. Magn Reson Med. 2018 Oct;80(4):1402–15.

19. Ma J, Singh SK, Kumar AJ, Leeds NE, Zhan J. T2-weighted spine imaging with a fast three-point dixon technique: comparison with chemical shift selective fat suppression. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2004 Dec;20(6):1025–9.

20. Del Grande F, Santini F, Herzka DA, Aro MR, Dean CW, Gold GE, et al. Fat-suppression techniques for 3-T MR imaging of the musculoskeletal system. Radiogr Rev Publ Radiol Soc N Am Inc. 2014 Feb;34(1):217–33.

Figures

Table 1: Image acquisition parameters. FR-FSE = fast-recovery fast spin-echo; TR=repetition time; TE=echo time; NSA = number of signal averages.

Table 2: Summary of the utilized Likert scale for lesion detection and assignment of level of suspicion. Lesions scored as ≥ 3 were considered suspicious.

Table 3: Summary of sensitivity of T2, DWI, and PET for detection of multiple myeloma focal lesions. Each row also indicates the lesions seen on one imaging sequence/modality, but not the other ones.

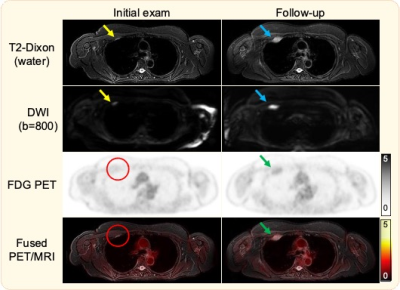

Figure 1. Initial T2-Dixon image demonstrates a hyperintense focal rib lesion, also seen on DWI (yellow arrows), but occult on PET (red circles). Follow up PET/MRI demonstrates lesion growth on T2-Dixon and DWI (blue arrows), but only mild uptake on PET. While both T2-Dixon and DWI depict the lesion, DWI suffers from several artifacts, including distortion that affects lesions size and shape, ghosting, and incomplete fat suppression in the shoulder region.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1442