1438

Alteration of sacroiliac fatty acids composition in axial spondyloarthritis: analysis using 3.0 T chemical shift-encoded MRI1Paul C. Lauterbur Research Center for Biomedical Imaging, Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenzhen, China, 2Radiology Department, Peking University Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Joints, Quantitative Imaging, axial spondyloarthritis; bone marrow; fatty acids

Changes of bone marrow fatty acids (FAs) composition have been detected in several inflammatory and metabolic diseases by MRI. However, the alteration of sacroiliac FAs composition in axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) remains unknown. We observed changes of bone marrow FAs composition of the sacroiliac joint in patients with axSpA compared to controls using chemical shift-encoded MRI (CSE-MRI). The changes differed between areas with fat metaplasia and areas without fat metaplasia in axSpA. Our results indicated bone marrow FAs including saturated FA, mono-unsaturated FA and poly-unsaturated FA may play different roles in the pathogenesis of axSpA.Introduction

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a group of inflammatory diseases that can cause chronic low back pain, stiffness and bone fusion of the axial skeleton1. Immunological alterations in axSpA lead to abnormal activity of osteoblasts, osteoclasts, fibroclasts and macrophages, and cause inflammation, bone erosion and abnormal bone proliferation2. MRI studies have shown that subchondral fat metaplasia in the sacroiliac joint is useful in diagnosis of axSpA and may play a key role in the development of joint ankylosis3, indicating bone marrow fat alteration may have a place in the disease pathogenesis. Triglycerides that contribute to MR signal of human lipids can be categorized as saturated (SFA), monounsatrurated (MUFA) and poly unsaturated (PUFA) fatty acids4. Changes of bone marrow fatty acids composition in osteoporosis, diabetes, osteoarthritis and systemic lupus erythematous has been detected in vivo using MRI5,6. The alteration of bone marrow fat saturation have not been investigated in axSpA. In this study, we aimed to bone marrow fatty acids composition of the sacroiliac joint in patients with axSpA compared to controls using chemical shift-encoded MRI (CSE-MRI).Methods

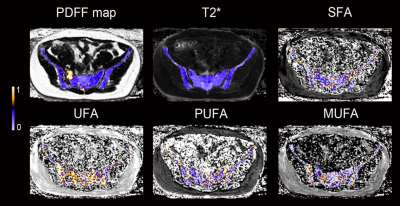

Patients with axSpA and non-SpA controls (age and body mass index matched) were prospectively included. All patients underwent an MRI scan of the sacroiliac joint on a clinical 3.0T MRI scanner (uMR780, United Imaging, Shanghai, China) with a 12-channel body flexed array coil. An additional multiple gradient-echo CSE-MRI protocol was added for fatty acids analysis, including two consecutively scanned 20-echo sequences. For sequence 1, the 20 TEs gave an echo train length of n= (1:20) × 1.58 ms. For sequence 2, the 20 TEs gave an echo train length of n= 0.78 + (1:20) × 1.58 ms. The other parameters were identical for the two sequences as following: repetition time (TR) = 35 ms, flip angle (FA) =5 °, receiver bandwidth = 900 Hz, number of averages (NA) = 1, field of view = 400 × 305 mm, acquisition matrix = 208 × 118, the reconstructed pixel resolution = 0.96 × 0.96 mm2, slice thickness = 2 mm, 48 axial slices, scan time = 1:04 minutes. Fatty acids maps were generated by previously described postprocessing methods7 using MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts). Regions of interest (ROIs) for FAs measurements were manually placed in the subchondral area of sacrum and ilium. In axSpA patients, ROIs were placed in areas with and without fat metaplasia.Regions with obvious bone marrow edema and sclerosis were avoided. The following intergroup comparison of proton-density fat fraction (PDFF), SFA, UFA, MUFA and PUFA was performed using independent t test: (1) areas with fat metaplasia in axSpA vs non-SpA, and (2) areas without fat metaplasia in axSpA vs non-SpA. Examples of FA maps are shown in Figure 1.

Results

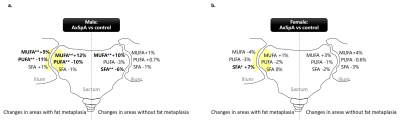

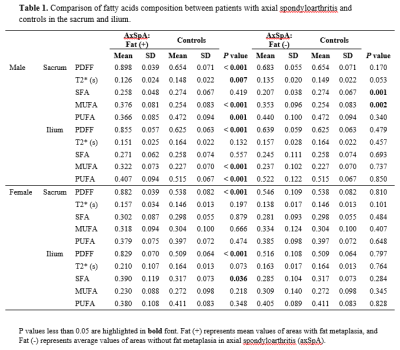

In total, 48 patients with axSpA (mean age, 32.5 ± 6.2 years, 25 male, 23 female,) and 37 non-SpA controls (mean age, 32.1 ± 6.1 years, 18 male, 19 female) were included. Results of FA composition analysis and comparison between axSpA vs. controls are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 2. In male, axSpA patients showed significant increase in MUFA (+12%, p<0.001), decrease in PUFA (-10%, p=0.001) in areas with fat metaplasia, and decrease in SFA (-6%, p=0.001), increase in MUFA (+10%, p=0.002) in areas without fat metaplasia in the sacrum; and significant increase in MUFA (+9%, p<0.001), decrease in PUFA (-11%, p<0.001) in areas with fat metaplasia of the ilium in comparison to controls. In female, significant change was found only in SFA in areas with fat metaplasia of the ilium (+7%, p=0.036) in patients with axSpA.Discussion

Previous studies indicated that SFA, MUFA, PUFA may have different roles on bone metabolism and inflammation process8. In general, our study showed a decrease of PUFA and increase of MUFA in axSpA, and the changes were more significant in male and in areas with fat metaplasia. PUFA was suggested to be protective for bone health through promoting osteoblastgenesis and enhancing osteoblastic activity8, and showed anti-inflammatory effects by reducing inflammatory cytokines production production9. Our finding indicated that PUFA may also play a role in the pathogenesis of axSpA. The role of MUFA on bone metabolism and inflammation was not consistent in literature. In our study, we found a significant increase of MUFA in the sacrum and ilium in male patients with axSpA, and a tendency of MUFA increase in the sacrum in female patients. In contrast, there was a tendency of decrease of MUFA in the ilium of female with axSpA. Most human in vitro studies suggested that SFA can induce inflammation and showed pro-inflammatory actions9. In our study, SFA decreased in areas without fat metaplasia and increased in areas with fat metaplasia in axSpA, and the changes were significant in the sacrum of male, and in the ilium of female, respectively. We hypothesized that the decrease of SFA in the areas without fat metaplasia in axSpA may represent a compensation in the disease procedure.Conclusion

In conclusion, our results indicated that bone marrow FAs composition of the sacroiliac joint alter in patients with axSpA and can be detected using CSE-MRI. Bone marrow FAs may play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the General Program for Clinical Research at Peking University Shenzhen Hospital (No. LCYJ2021007) and Shenzhen High-level Hospital Fund.References

1. Taurog JD, Chhabra A, and Colbert RA, Ankylosing Spondylitis and Axial Spondyloarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374: 2563-2574.

2. Simone D, Al Mossawi MH, and Bowness P, Progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018; 57: vi4-vi9.

3. Maksymowych WP, Wichuk S, Chiowchanwisawakit P, et al. Fat metaplasia on MRI of the sacroiliac joints increases the propensity for disease progression in the spine of patients with spondyloarthritis. RMD Open. 2017; 3: e000399

4. Peterson P, Trinh L, and Mansson S, Quantitative (1) H MRI and MRS of fatty acid composition. Magn Reson Med. 2021; 85: 49-67

5. Martel D, Saxena A, Belmont HM, et al. Fatty Acid Composition of Proximal Femur Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue in Subjects With Systemic Lupus Erythematous Using 3 T Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2022; 56:618-624

6. Martel D, Leporq B, Bruno M, et al. Chemical shift-encoded MRI for assessment of bone marrow adipose tissue fat composition: Pilot study in premenopausal versus postmenopausal women. Magn Reson Imaging. 2018; 53: 148-155

7. Hamilton G, Yokoo T, Bydder M, et al. In Vivo Characterization of the Liver Fat (1)H Mr Spectrum. NMR Biomed. 2011; 24:784-790

8. Dragojevic J, Zupan J, Haring G, et al. Triglyceride metabolism in bone tissue is associated with osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation: a gene expression study. J Bone Miner Metab. 2013; 31: 512-519

9. Masoodi M, Kuda O, Rossmeisl M, et al. Lipid signaling in adipose tissue: Connecting inflammation & metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015; 1851: 503-518

Figures