1436

Post-ablation Changes in Left Atrial Hemodynamics and Volume in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation1Department of Radiology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States, 2Department of Radiology, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland, 3Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States, 4Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Flow, Velocity & Flow

Atrial fibrillation (AF) leads to detrimental changes in the left atrial (LA) and left atrial appendage’s (LAA) hemodynamics and volumes. When indicated, AF ablation is used to reduce AF burden. We recruited 17 post-ablation patients, 10 of whom had no documented AF recurrences. 4D flow MRI was acquired, immediately before and 6-12months after ablation, and quantified for LA and LAA stasis, volume, and peak velocities. Our findings support the notion that restoration of sinus rhythm corrects the deleterious changes of AF.

Introduction

AF is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, with its prevalence expected to exceed 12 million by 2030 in the US alone1. The most serious complication of AF is stroke, attributed to embolism of thrombus originating in the left atrium (LA) and LA appendage (LAA). There is strong evidence that changes in LA and LAA flow in AF can initiate thrombus formation and thus, increased risk for stroke. Cardiac catheter ablation (CCA) is one option for rhythm control treatment but its impact on stroke prevention is uncertain. The direct impact of CCA on atrial flow hemodynamics is also not well understood, and it remains unclear whether restoring sinus rhythm improves atrial hemodynamics and volumes.4D flow MRI can measure time-resolved 3D blood flow velocities with volumetric coverage of the heart, allowing for quantification of atrial hemodynamics. Our 4D flow studies in AF patients have found reduced peak velocities and increased blood stasis in the LA and LAA2, indicating AF-associated atrial flow impairment and increased risk for thromboembolism.

The aim of this study was to apply 4D flow MRI in a longitudinal study with AF patients, pre- and post-CCA, to explore ablation induced changes in left atrial volume and flow parameters in two groups of AF patients, those with ablation success and those with AF recurrence.

Methods

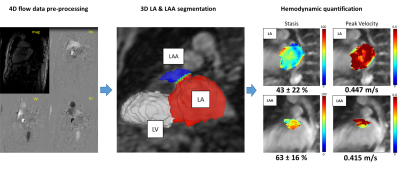

We enrolled 17 patients who underwent CCA; 7 patients reverted to AF and 10 patients maintained sinus rhythm. All patients underwent baseline (2-7 days prior to CCA) and follow-up (6-12 months after CCA) 4D-flow MRI (1.5 T systems, Siemens Healthineers, Germany). Patients had a 3 month “blanking period” post-CCA, after which they were evaluated by intermittent cardiac rhythm monitoring (≥ 24 hours) for ablation success (sinus rhythm) or recurrence of AF.The data analysis workflow is illustrated in Figure 1. 4D flow data were pre-processed for eddy current background phase correction. A phase contrast magnetic resonance angiogram was generated and used for manual 3D segmentation of the LA and LAA using a dedicated software (Mimics, Materialise 20.0, USA). The 3D LA and LAA segmentations were used to calculate atrial volumes, to mask the 4D flow MRI data, and to calculate peak velocity and blood stasis maps. LA and LAA peak velocities were calculated as the 95th percentile of velocities to mitigate noise. LA and LAA blood stasis were calculated as the % of the cardiac cycle with velocities <0.1 m/s and averaged over the LA or LAA.

Results

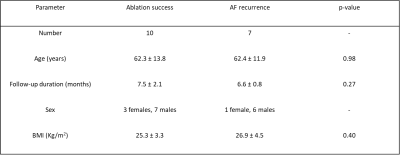

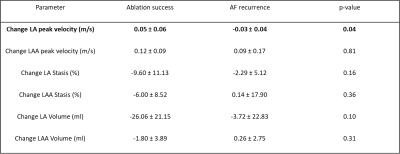

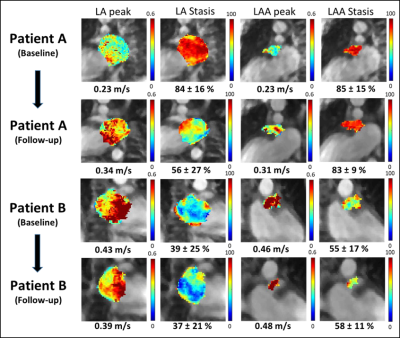

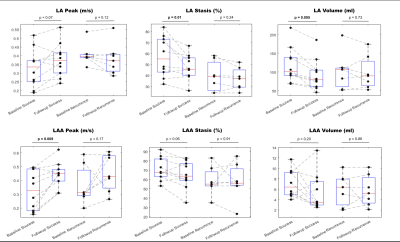

Baseline patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Examples of baseline and follow-up LA and LAA flow parameter maps (stasis and peak velocity) for 2 patients are shown in figure 2. A patient with ablation success (figure 2, patient A) demonstrated improved post-CCA flow, including increased LA and LAA peak velocities, and decreased LA and LAA stasis. A patient with AF recurrence (figure 2, Patient B) had decreased LA and LAA peak velocities, decreased LA stasis, and increased LAA stasis.Results of all AF patients in the ablation success group demonstrated clear signs of improved LA and LAA hemodynamics (Figure 3), including increased LAA peak velocity from baseline to follow-up (0.32 ± 0.14 vs. 0.44 ± 0.09 m/s, p=0.009) and decreased LA blood stasis (57.1 ± 18.1 vs. 47.5 ± 11.5 %, p=0.01). In addition, a significant decrease in LA volume was observed (118.4 ± 46.9 vs. 92.3 ± 41.8 ml, p=0.005). In contrast, measures of LA and LAA hemodynamics remained unchanged in patients in the AF recurrence group (figure 3) and no significant differences were found between baseline and follow-up 4D flow MRI (p>0.12). These findings are corroborated by a significant difference (p=0.04) in baseline vs. follow-up changes of peak LA velocity between ablation success and AF recurrence groups (0.05 ± 0.06 m/s vs. -0.03 ± 0.04 m/s, Table 2).

Discussion

Our study findings indicate that the maintenance of sinus rhythm following CCA may be an important factor in reversing the deleterious effects that AF has on LA and LAA hemodynamics and volumes.It has been demonstrated that AF is correlated with impaired LA flow hemodynamics, and that a return to sinus rhythm after ablation nearly restores normal LA hemodynamics, and leads to an overall decrease in LA size3,4. Evidence has also shown that such geometrical remodeling can occur within a year of undergoing CCA3. In our cohort, LA volume and stasis decreased significantly in the ablation success group. These findings highlight that maintaining a sinus rhythm could play a role in improving LA hemodynamics and volume.

Our finding of a significant increase in LAA peak velocity in the success group depicts another improved hemodynamic change post-ablation. This is important since evidence shows that a reduced LAA velocity in patients with AF is associated with thrombus formation5.

Limitations

Heart rate variability has been linked to slower LA velocity and elevated stasis6. Thus, controlling for heart rate variability during scan acquisition could allow for more accurate parameter measurements. Another limitation is the small sample size.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Tanaka, Y., Shah, N. S., Passman, R., Greenland, P., Lloyd‐Jones, D. M., & Khan, S. S. (2021). Trends in cardiovascular mortality related to atrial fibrillation in the United States, 2011 to 2018. Journal of the American Heart Association, 10(15).

2. Markl, M., Lee, D. C., Furiasse, N., Carr, M., Foucar, C., Ng, J., Carr, J., & Goldberger, J. J. (2016). Left atrial and left atrial appendage 4D blood flow dynamics in atrial fibrillation. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging, 9(9).

3. Reant, P., Lafitte, S., Jaïs, P., Serri, K., Weerasooriya, R., Hocini, M., Pillois, X., Clementy, J., Haïsaguerre, M., & Roudaut, R. (2005). Reverse remodeling of the left cardiac chambers after catheter ablation after 1 year in a series of patients with isolated atrial fibrillation. Circulation, 112(19), 2896-2903.

4. Xiong, B., Li, D., Wang, J., Gyawali, L., Jing, J., & Su, L. (2015). The effect of catheter ablation on left atrial size and function for patients with atrial fibrillation: an updated meta-analysis. PLoS One, 10(7).

5. Goldman, M. E., Pearce, L. A., Hart, R. G., Zabalgoitia, M., Asinger, R. W., Safford, R., & Halperin, J. (1999). Pathophysiologic correlates of thromboembolism in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: I. Reduced flow velocity in the left atrial appendage (The Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation [SPAF-III] study). Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, 12(12), 1080-1087.

6. DiCarlo, A., Baraboo, J., Collins, M. A., Pradella, M., McCarthy, P. M., Greenland, P., Arora, R., Lee, D.C., Kim, D., Markl, M., & Passman, R. S. (2021). Heart rate variability and left atrial hemodynamics in atrial fibrillation measured with 4D flow MRI. Heart Rhythm, 18(8), S310.

Figures