1428

Diabetic Treatment and Oral Ketone Supplement effect on Cardiac Function and Metabolism in Heart Failure Model by Cardiac and hyperpolarized MRSI1Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging,Radiology Department, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, United States, 2Polarize ApS, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 3Corrigan Minehan Heart Center, Division of Cardiology, Massachusetts. General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 4Cardiovascular Innovation Research Center, Heart, Vascular, and Thoracic Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States, 5Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Cardiomyopathy, Hyperpolarized MR (Non-Gas), Heart Failure, Contrast Agent, Contrast Mechanisms, Metabolism

Using hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate MR spectroscopy imaging and cine MRI, we show that targeting cardiometabolic dysregulation with metabolic treatment, such as ketone ester supplementation and/or sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, was effective in improving cardiac function and ameliorating cardiac remodeling in a preclinical model of HFpEF. These results provide a rationale for the assessment of metabolic interventions for patients with HFpEF.Introduction

As most patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction(HFpEF) have a common cardiometabolic phenotype with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus(T2DM), cardiometabolic dysregulation has been implicated in the disease pathogenesis[1,2]. Evidence from failing human and rodent hearts has suggested that the reductions in carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolism are partially overcome by a compensatory increase in the ketone body oxidation both in HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and preserved fraction (HFpEF)[3]. We and others recently discovered the beneficial effects of exogenous ketone supplementation in studies of small animal models and humans with HFrEF[3,4]. Moreover, we and others also observed that a relevant feature of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2(SGLT2) inhibitors in HFrEF is the increase in circulating ketone bodies, which has been proposed to mediate part of the beneficial effects of this class of drugs[5]. With the heart being one of the largest energy consumer organs in the body[6], ketone bodies could serve as potential treatment for patients with HFpEF. In this work, we examined the efficacy of therapy with empagliflozin and oral ketone supplement in HFpEF rats using cine MRI and hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate MR spectroscopy imaging (HP13C-MRSI) to assess cardiac function and metabolism, respectively. For the hyperpolarized MRSI experiments, dissolution Dynamic Nuclear polarization (d-DNP)[7] was used, a promising technique for the study of cardiac metabolism[8–11]. Histological and molecular markers of cardiac remodeling were also assessed in the left ventricle.Methods

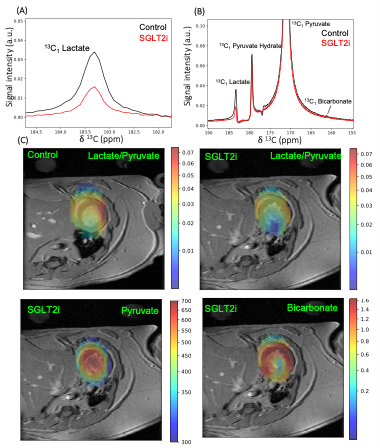

Four groups of 20 weeks old obese ZSF-1 rats received isocaloric diet containing vehicle, empagliflozin, ketone ester (KE), or combination of empagliflozin and KE for 12 weeks. Cardiac MRI and HP13C-MRSI were performed in the same imaging session for each rat on a 4.7 T Bruker preclinical scanner (Biospin, Bruker, Germany). A cine fast GRE sequence was used for cardiac MRI and segmentation of left ventricle to quantify the left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) was performed by using Segment software (Medviso, Sweden).[1-13C]pyruvate samples consisting of 18 L of neat [1-13C]pyruvic acid and 30mM trityl (AH111501) were hyperpolarized in a 6.7 T dissolution-DNP[7] polarizer (SpinAligner, Polarize, Denmark)[12]. HP13C-MRSI was acquired on a single midventricular slice of 8mm with a chemical shift imaging(CSI) sequence starting 5s after the start of HP [1-13C]pyruvate injection (100mM and ~6.5 mL/kg in 14 seconds). Spectra were phased and baseline corrected for each metabolic peak at each pixel. Maps of individual metabolite were derived from integrated peak area of individual metabolite at each pixel(Fig. 3).

After imaging experiments, animals were euthanized for the assessment of histological and molecular markers of the left ventricle. To measure cardiac expression (mRNA levels) of cardiac remodeling markers, RNA was extracted from the left ventricle using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Corp.,Carlsbad, CA, USA). QuantiTect RT kit(Qiagen) was then used to make cDNA, following manufacturer's instructions. mRNA levels obtained by a qRT-PCR using QuantStudio™5 Real-Time PCR System(Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). 36B4 reference genes were used to correct all measured mRNA expression. For cardiomyocyte cell size quantification, the mid-papillary slice of the left ventricle was fixed in 4% formaldehyde and paraffin embedded. FITC-labelled wheat germ agglutinin was performed to evaluate the cardiomyocyte cell size.

Results

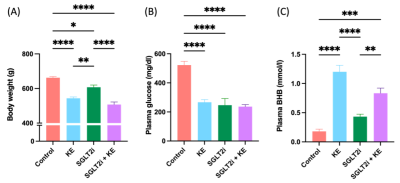

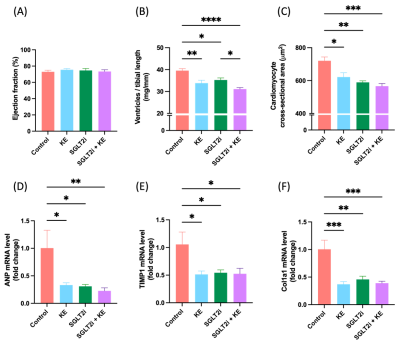

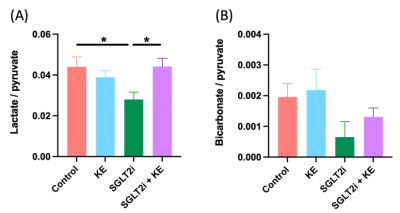

Decreased body weight (Fig. 1A), reduced blood glucose levels (Fig. 1B), and increased circulating beta hydroxy-butyrate (βHB) levels (Fig. 1C) were observed in the treatment groups (all p<0.05). EF was preserved in all groups (Fig. 2A). All treatment regiments significantly decreased ventricular hypertrophy (Fig. 2B)(all p<0.05). In addition, cardiomyocyte size (Fig. 2C) and the expression of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP)(Fig. 2D) and fibrosis markers, col1a1 (Fig. 2E) and TIMP1(Fig. 2F), were significantly attenuated by all treatment (all p<0.05). HP13C-MRSI yielded pyruvate, lactate, and bicarbonate maps and metabolite spectrum at each pixel(Fig. 3). Hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate imaging detected a decrease in lactate/pyruvate ratio(Fig. 4A).Discussion

This study was designed to determine whether increasing ketone delivery to the hearts by chronic administration of either empagliflozin, KE, or combination of empagliflozin and KE could reduce the severity of HF and change cardiac metabolism in obese ZSF-1 rats. All animals in our study indeed presented with preserved ejection fraction (Fig. 2A). Treatment with ketone ester and empagliflozin resulted in significant elevation of circulating βHB (Fig. 1C), suggesting that the ketone delivery to the heart is also increased as cardiac ketone oxidation is known to be proportional to its arterial concentrations[6]. The unique feature of treatment with SGLT2i is a reduction in insulin/glucagon ratio, thus promoting a modest increase in ketone levels[13](Fig. 1C). Our HP13C-MRSI data further extend this observation as we demonstrate a reduction in lactate/pyruvate ratio(Fig. 3) only in empagliflozin group (Fig. 4A) suggesting increased gluconeogenesis in the hearts. Interestingly, treatment with empagliflozin, KE, or combination of both treatment strategies favorably affects body weight (Fig. 1A), blood glucose (Fig. 1B), cardiac hypertrophy (Fig. 2B,2C, 2D) and fibrosis(Fig. 2E,2F). Taken together, our data suggest that targeting cardiometabolic dysregulation might be of benefit in patients with HFpEF.Conclusion

Obese ZSF1 rats recapitulates many aspects of clinical HFpEF with predominant background of obesity and diabetes. We show that targeting cardiometabolic dysregulation was effective in ameliorating cardiac remodeling in a preclinical model of HFpEF. These results provide a rationale for the assessment of metabolic interventions for patients with HFpEF.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH funds S10OD021768, R21GM137227[1] M. A. Pfeffer, A. M. Shah, B. A.References

[1] M. A. Pfeffer, A. M. Shah, B. A. Borlaug, Circ Res 2019, 124, 1598–1617.

[2] P. Meagher, M. Adam, R. Civitarese, A. Bugyei-Twum, K. A. Connelly, Canadian Journal of Cardiology 2018, 34, 632–643.

[3] K. C. Bedi, N. W. Snyder, J. Brandimarto, M. Aziz, C. Mesaros, A. J. Worth, L. L. Wang, A. Javaheri, I. A. Blair, K. B. Margulies, J. E. Rame, Circulation 2016, 133, 706–716.

[4] S. R. Yurista, T. R. Matsuura, H. H. W. Silljé, K. T. Nijholt, K. S. McDaid, S. v. Shewale, T. C. Leone, J. C. Newman, E. Verdin, D. J. van Veldhuisen, R. A. de Boer, D. P. Kelly, B. D. Westenbrink, Circ Heart Fail 2021, 14, DOI 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.007684.

[5] S. R. Yurista, C. T. Nguyen, A. Rosenzweig, R. A. de Boer, B. D. Westenbrink, Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2021, 32, 814–826.[6] S. R. Yurista, C.-R. Chong, J. J. Badimon, D. P. Kelly, R. A. de Boer, B. D. Westenbrink, J Am Coll Cardiol 2021, 77, 1660–1669.

[7] J. H. Ardenkjær-Larsen, B. Fridlund, A. Gram, G. Hansson, L. Hansson, M. H. Lerche, R. Servin, M. Thaning, K. Golman, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2003, 100, 10158–10163.

[8] K. Golman, J. S. Petersson, P. Magnusson, E. Johansson, P. Åkeson, C.-M. Chai, G. Hansson, S. Månsson, Magn Reson Med 2008, 59, 1005–1013.

[9] C. H. Cunningham, J. Y. C. Lau, A. P. Chen, B. J. Geraghty, W. J. Perks, I. Roifman, G. A. Wright, K. A. Connelly, Circ Res 2016, 119, 1177–1182.

[10] M. A. Schroeder, K. Clarke, S. Neubauer, D. J. Tyler, Circulation 2011, 124, 1580–1594.

[11] J. J. Miller, D. R. Ball, A. Z. Lau, D. J. Tyler, NMR Biomed 2018, 31, e3912.

[12] J. H. Ardenkjær‐Larsen, S. Bowen, J. R. Petersen, O. Rybalko, M. S. Vinding, M. Ullisch, N. Chr. Nielsen, Magn Reson Med 2019, 81, 2184–2194.

[13] E. Ferrannini, S. Baldi, S. Frascerra, B. Astiarraga, T. Heise, R. Bizzotto, A. Mari, T. R. Pieber, E. Muscelli, Diabetes 2016, 65, 1190–1195.

Figures