1422

Single-shot 2D spiral and echo planar imaging at 7 and 10.5 Tesla with field monitoring and correction1CMRR, Radiology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States, 2Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 3University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: High-Field MRI, Data Acquisition, Brain imaging

Interest in pursuing MRI at ultra-high field (UHF) is increasing owing to increased SNR. However, MRI at UHF presents acquisition challenges due to decreased T2* and worsened field inhomogeneities. Rapid sampling strategies such as spiral and echo planar (EPI) acquisitions have been proposed to help mitigate these challenges. Incorporation of field monitoring to UHF applications has been demonstrated to improve the reconstruction of these images thanks to direct measurement and correction of spatiotemporal phase accrual. Here we demonstrate field-monitoring-enabled spiral and EPI acquisitions using Pulseq and field cameras.Introduction

Interest in pursuing structural and functional MRI at ultra-high field (UHF) is increasing owing to the ability to acquire high-resolution images with improved SNR and contrast-to-noise ratios. However, MRI at UHF presents acquisition challenges due to decreased T2* and worsened field inhomogeneities. Rapid sampling strategies such as spiral and echo planar (EPI) acquisitions have been proposed to help mitigate these challenges owing to their fast traversal of k-space. Incorporation of field monitoring to UHF applications has been demonstrated to improve the reconstruction of these images thanks to direct measurement and correction of spatiotemporal phase accrual (1,2).Here we demonstrate field-monitoring-enabled spiral and EPI sequences using Pulseq (3), which are ported without recompilation to 7 Tesla (7T) and 10.5T. Utilizing this environment allows researchers to rapidly validate sequences at lower field strengths and then translate the sequences to higher field strengths for further investigation.

Methods

We collected human data on a Siemens 7T Terra MR scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using the commercial Nova 32-channel receive RF head coil (Nova Medical, Wilmington, USA) and phantom data on a Siemens 10.5T Dotplus MR scanner using a custom 16-channel transceiver RF array, both scanners being equipped with a body gradient allowing for 200 T/m/s maximum slew rate and 80 mT/m maximum strength. Human data is not available for this RF coil configuration at 10.5T at the present since all RF coil configurations need FDA approval at 10.5T. A male volunteer who signed a consent form approved by the local Institutional Review Board was scanned at 7T and a head-shaped agar phantom was scanned at 10.5T. In both cases, EPI and spiral gradient echo (GRE) images with different k-space undersampling rates were acquired from a single transverse slice located at the isocenter. Relevant imaging parameters are listed in Fig. 1. All EPI and spiral image acquisitions were implemented using the pulseq framework (3). Second-order B0 shimming was performed to reduce susceptibility-induced off-resonance effects inside the target slice before image acquisition.For both 7T and 10.5T scans, we performed field monitoring with a clip-on field camera (Skope MRT, Zurich, Switzerland). Field data were acquired by a Skope acquisition system (a standalone spectrometer) (4) from a set of 16 19F NMR field probes (5). For 7T scan, the probes were placed around the head in between the transmit and receive portions of the Nova coil for concurrent field monitoring, whereas for 10.5T scan, the probes were mounted to a scaffold placed inside the RF coil for separate field monitoring. In both cases, to synchronize image acquisition and field monitoring, the clock of the Skope acquisition system was locked to that of the MR scanner. For a given image readout, the difference in time delay between the MR scanner and Skope acquisition system was corrected based on pre-scans.

We conducted image reconstructions using the Skope image reconstruction software package. Image reconstruction was based on an expanded signal model (6) including contributions from static dB0, dynamic field changes, and coil sensitivities. The static dB0 and multi-coil sensitivity maps were obtained from a double-echo GRE image acquisition of the same slice at 2-mm resolutions. Image reconstruction was fulfilled by inverting the signal model via an extended iterative conjugate-gradient SENSE algorithm (7-9).

Results

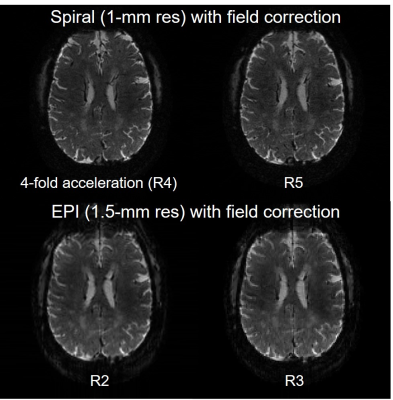

Concurrent field monitoring on the Terra successfully characterized the entire readout for both spiral and EPI acquisitions (Fig. 2) and so did separate field monitoring at 10.5T (Fig. 5).Accordingly, the image reconstruction with correction of static dB0 and dynamic field changes (up to second-order terms of the spherical harmonic basis set) led to good image quality on the Terra (Fig. 3), with reduced distortion or blurring observed with increased acceleration.

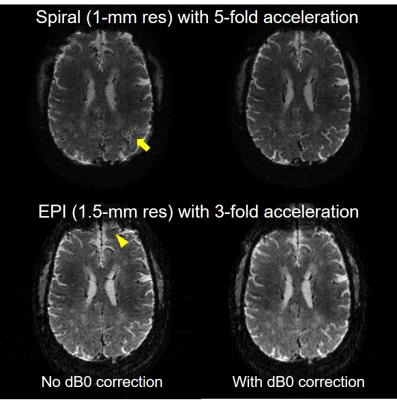

Incorporation of dB0 maps into image reconstruction for correction of static dB0 was important to ensuring image quality (Fig. 4).

Discussion

We have demonstrated successfully the feasibility of single-shot 2D spiral imaging at both 7T and 10.5T using the same sequence on both scanners. Critical to this success was the use of a field camera system for magnetic field monitoring in combination of an extended iterative conjugate-gradient SENSE algorithm enabling image reconstruction with simultaneous corrections of static dB0 and dynamic field changes. Our results also showed the utility of this combination for single-shot 2D EPI at both 7T and 10.5T.Our immediate next step is to refine our workflow and acquire field-monitored neuroimaging data at 10.5T.

Conclusion

It is feasible to perform spiral and EPI acquisitions at both 7T and 10.5T with field monitoring and correction using open-source sequence development environments.Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply indebted to Cameron Cushing and Paul Weavers from Skope MRT for their indispensable contribution to this work. This work was supported in part by NIH grants NIBIB P41 EB027061 and NIH U01 EB025144.References

1. Kasper L, Engel M, Barmet C, Haeberlin M, Wilm BJ, Dietrich BE, Schmid T, Gross S, Brunner DO, Stephan KE, Pruessmann KP. Rapid anatomical brain imaging using spiral acquisition and an expanded signal model. Neuroimage 2018;168:88-100.

2. Vannesjo SJ, Wilm BJ, Duerst Y, Gross S, Brunner DO, Dietrich BE, Schmid T, Barmet C, Pruessmann KP. Retrospective correction of physiological field fluctuations in high-field brain MRI using concurrent field monitoring. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2015;73(5):1833-1843.

3. Layton KJ, Kroboth S, Jia F, Littin S, Yu H, Leupold J, Nielsen JF, Stöcker T, Zaitsev M. Pulseq: A rapid and hardware-independent pulse sequence prototyping framework. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2017;77(4):1544-1552.

4. Dietrich BE, Brunner DO, Wilm BJ, Barmet C, Gross S, Kasper L, Haeberlin M, Schmid T, Vannesjo SJ, Pruessmann KP. A Field Camera for MR Sequence Monitoring and System Analysis. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2016;75(4):1831-1840.

5. De Zanche N, Barmet C, Nordmeyer-Massner JA, Pruessmann KP. NMR probes for measuring magnetic fields and field dynamics in MR systems. Magn Reson Med 2008;60(1):176-186.

6. Wilm BJ, Barmet C, Pavan M, Pruessmann KP. Higher Order Reconstruction for MRI in the Presence of Spatiotemporal Field Perturbations. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2011;65(6):1690-1701.

7. Kasper L, Haeberlin M, Dietrich BE, Gross S, Barmet C, Wilma BJ, Vannesjo SJ, Brunner DO, Ruff CC, Stephan KE, Pruessmann KP. Matched-filter acquisition for BOLD fMRI. Neuroimage 2014;100:145-160.

8. Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Börnert P, Boesiger P. Advances in sensitivity encoding with arbitrary k-space trajectories. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2001;46(4):638-651.

9. Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P. SENSE: Sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 1999;42(5):952-962.

Figures

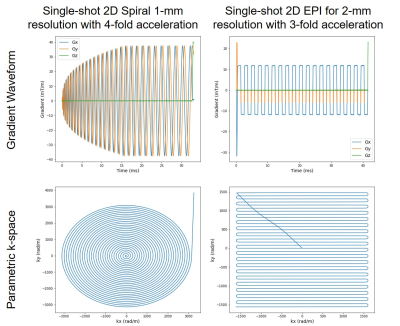

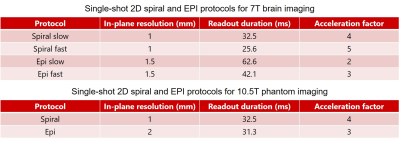

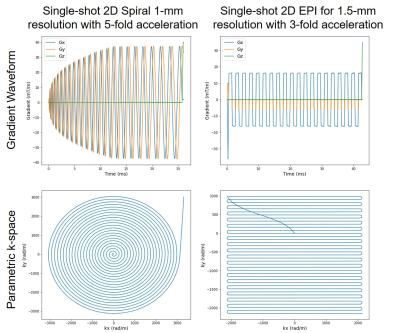

Fig. 1. Single-shot 2D spiral and EPI protocols used in the current preliminary study for 7T brain imaging (top) and 10.5T phantom imaging (bottom). All image data were acquired from a single transverse slice located at the isocenter. All EPI data were obtained with a partial Fourier factor of 6/8. Other relevant imaging parameters common to both spiral and EPI acquisitions were: FOV = 230 mm, slice thickness = 2 mm, TE/TR = 22/400 ms, nominal excitation flip angle = 25 degrees, nominal fat saturation flip angle = 110 degrees.

Fig. 2. Concurrent field measurement on 7T Terra for single-shot 2D spiral (left panel) and EPI (right panel) readouts. In each case, shown are measured gradient waveforms (top) and corresponding k-space trajectories (bottom). The spiral readout (<26 ms in length) was an Archimedean spiral designed to achieve 1-mm in-plane resolutions with 5-fold k-space acceleration, whereas the EPI readout (<43 ms in length) was a standard EPI designed to achieve 1.5-mm in-plane resolutions with 3-fold k-space acceleration along with a partial Fourier factor of 6/8.

Fig. 3. Single-shot spiral and EPI acquisitions of the human brain with concurrent field monitoring on 7T Terra. Shown are offline image reconstructions with correction of static dB0 and dynamic field changes (up to second order terms) using an expanded signal model and based on data acquisition using protocols reported in Fig. 1. In all cases, the commercial Nova 1-channel transmit and 32-channel receive RF coil was used for data acquisition while a set of 19F NMR field probes placed between the transmit and receive portions of the Nova coil were used for concurrent field monitoring.

Fig. 4. Importance of static dB0 correction in fast spiral and EPI readout. Shown are the offline image reconstructions using the expanded signal model without (left) and with (right) dB0 correction, all with dynamic field corrections (up to second-order spherical harmonic basis terms). Note how including dB0 correction effectively improved image quality, reducing the otherwise blurring artifact (as indicated by the arrow) in spiral imaging and geometric distortion (as indicated by the arrowhead) in EPI.