1394

Visualizing Neuromelanin in Parkinson’s disease in the presence of motion1Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, 2Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Synopsis

Keywords: Parkinson's Disease, Motion Correction

Neuromelanin-MRI can detect reductions in volume and intensity of the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease (PD). High-resolution magnetization transfer (MT) contrast T1-weighted sequences are used, and the MT pulse is time-consuming. We evaluated the degree of motion during a long (~ 12 min) scan in a PD patient and a healthy volunteer, and the effect of motion correction using a wireless RF-triggered acquisition device (WRAD) developed in our group. Despite only minor motion, for both participants, motion correction improved image quality.Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder with resting tremor, muscular rigidity and bradykinesia, in which symptoms can overlap with other diseases such as progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy. The pathology process involves loss of dopaminergic cells and reduction of neuromelanin in the substantia nigra (SN), as well as accumulation of iron (1-3). There is no specific test for PD, and it is a clinical diagnosis based on symptoms and neurological examination. However, structural MRI of the SN is now showing promising results in diagnosing PD. Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) can detect iron accumulation in a small area in the SN, the nigrosome 1, with localized loss of hyperintensity in PD, which is the same as disappearance of the ’swallow tail sign’ (4-6). However, in a 7T study it was found that the hyperintensity was not fully correlated to nigrosome 1 (7). Additionally, high-resolution magnetization transfer (MT) contrast T1-weighted images of the SN, neuromelanin-magnetic resonance imaging (NM-MRI), shows reduction in volume and intensity in PD, which also correlates with disease severity (8-13). Due to the MT pulse, NM-MRI is time-consuming. In a recent review of NM-MRI, scan times were: 12.5-9.5 min, 12 min, 12 min, 9.6 min, 8 min, 8 min, 7.45-7.25 min, 6.9 min, 4.5 min and 4.25 min (14).Our group is currently developing a wearable battery operated device called a WRAD, a wireless RF-triggered acquisition device (figure 1), which is effective for prospective motion correction in conventional sequences (15). In this study, we investigated if WRAD could correct for small involuntary motion during a long NM-MRI acquisition.

Methods

Two imaging sessions were performed each with informed consent and approval from the local ethics review board. One on a patient diagnosed with Parkinson's disease in 2019 Hoehn & Yahr stage 2 (PD patient), and the second on a healthy volunteer (Healthy). Each session consisted of three scans. A 3D 0.7 mm isotropic susceptibility weighted EPI pulse sequence - included for diagnostic reasons - and two acquisitions of a 0.8 mm isotropic 3D magnetisation transfer (MT) weighted (300 degree flip angle 8 ms long Fermi pulse at 1.2 kHz off-resonance) spoiled gradient echo pulse sequence (MT-SPGR). For both MT-SPGR acquisitions the subject’s motion was tracked by mounting a WRAD to their forehead (figure 1). For one of the scans the motion parameters were used to perform prospective motion correction (co), and for the other no updates of the FOV were applied (noco).For these scan parameters the TR (18.9 ms) of the MT-SPGR was SAR limited, the WRAD navigators (2.4 ms) therefore had no impact on the scan duration (~ 12 min). For the Healthy scan, WRAD navigators were played out in opposing polarity and then combined, as described in (15). This improves the precision of the estimates at the cost of reducing the update frequency by a factor of two (1 / 2TR). For the PD patient scan, one estimate was generated for each navigator resulting in an update frequency of (1 / TR). Prospective updates, when enabled, were applied to the following TR without any temporal smoothing/filtering in each case.

Results

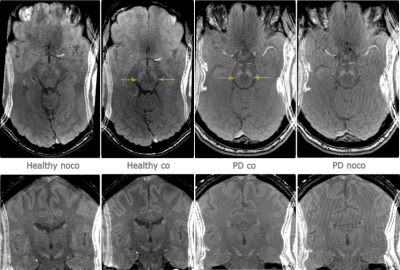

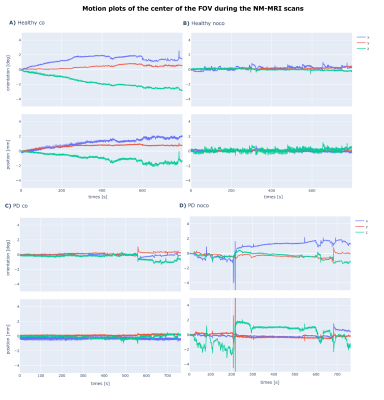

Neuromelanin in the SN was successfully visualized with a 12 minutes long MT-SPGR scan. When the WRAD was used for motion correction, SN was better delineated with improved contrast versus adjacent hypointense midbrain structures (figure 2). Although motion plots (figure 3) revealed minor motion of just a few millimeters, in both the non-corrected and motion corrected scans for the PD patient and the healthy volunteer, the effect of motion correction was distinct on SN and cortical gray-white matter interface.Discussion

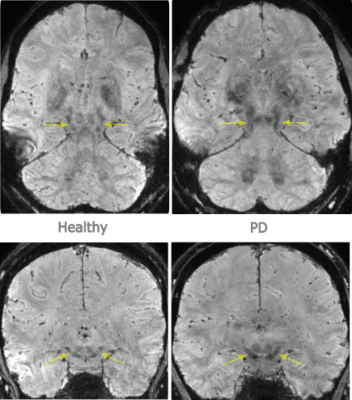

The PD patient had mild symptoms and a short disease duration of 3 years, and as expected only minor signs of loss of NM posterolateral in the SN was seen (figure 2) (16). NM-MRI images in our study were reformatted in 3 mm slices, as a review has indicated that ≥ 2mm are preferable, where factors attributed to heterogeneity in diagnostic performance were slice thickness, SN volumes or signal intensities, segmentation methods and disease duration (14).For diagnostic reasons, a high-resolution isotropic 3D SWI was also included, with images reformatted along with and orthogonal to the long axis of the midbrain, to evaluate the ’swallow tail sign’, which was lost in the PD patient (figure 4) (7, 17). The SWI sequence was not motion corrected, since this is a non-trivial problem due to motion induced changes in the B0 magnetic field (18).

Conclusion

Even minor motion can affect image quality in neuromelanin-MRI, which was improved by motion correction using a wireless RF-triggered acquisition device (WRAD).Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Bae YJ, Kim JM, Sohn CH, Choi JH, Choi BS, Song YS, Nam Y, Cho SJ, Jeon B, Kim JH. Imaging the Substantia Nigra in Parkinson Disease and Other Parkinsonian Syndromes. Radiology 2021;300:260-78.

2. Braak H., del Tredici K., Rüb U., de Vos R. A. I., Jansen Steur E. N. H., Braak E. (2003). Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 24 197–211.

3. Foley PB,Hare DJ, Double KL. A brief history of brain iron accumulation in Parkinson disease and related disorders.J Neural Transm (Vienna), 2022 Jun;129(5-6):505-520.

4. Cheng Z, He N, Huang P, Li Y, Tang R, Sethi SK, Ghassaban K, Yerramsetty KK, Palutla VK, Chen S, Yan F, Haacke EM. Imaging the Nigrosome 1 in the substantia nigra using susceptibility weighted imaging and quantitative susceptibility mapping: An application to Parkinson's disease. Neuroimage Clin 2020;25:102103.

5. Reiter E, Mueller C, Pinter B, Krismer F, Scherfler C, Esterhammer R, et al. Dorsolateral nigral hyperintensity on 3.0T susceptibility-weighted imaging in neurodegenerative parkinsonism. Mov Disord. 2015;30(8):1068–76.

6. Schwarz ST, Afzal M, Morgan PS, Bajaj N, Gowland PA, Auer DP. The 'swallow tail' appearance of the healthy nigrosome - a new accurate test of Parkinson's disease: a case-control and retrospective cross-sectional MRI study at 3T. PLoS One 2014;9:e93814.

7. Malte Brammerloh M, Kirilina E, Alkemade A, Bazin P-L, Jantzen C, Jäger C, Herrler A, Pine KJ, Gowland PA, Morawski M, Forstmann BU, Weiskopf N. Swallow Tail Sign: Revisited. Radiology 2022; 000:1–4.

8. van der Pluijm M, Cassidy C, Zandstra M et al (2020) Reliability and reproducibility of neuromelanin-sensitive imaging of the substantia nigra: a comparison of three different sequences. J Magn Reson Imaging 53:712–721.

9. Kashihara K., Shinya T., Higaki F. (2011). Neuromelanin magnetic resonance imaging of nigral volume loss in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Clin. Neurosci. 18 1093–1096.

10. Isaias, I. U. et al. Neuromelanin imaging and dopaminergic loss in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 8, 196 (2016).

11. Prasad S., Stezin A., Lenka A., George L., Saini J., Yadav R., Pal P.K. Three-dimensional neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging of the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2018;25:680–686.

12. Sasaki M., Shibata E., Tohyama K., Takahashi J., Otsuka K., Tsuchiya K., et al. (2006). Neuromelanin magnetic resonance imaging of locus ceruleus and substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroreport 17 1215–1218.

13. He N, Chen Y, LeWitt PA, Yan F, Haacke EM. Application of Neuromelanin MR Imaging in Parkinson Disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 2022 Aug 26. Online ahead of print.

14. Cho SJ, Bae YJ, Kim JM et al (2021) Diagnostic performance of neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging for patients with Parkinson’s disease and factor analysis for its heterogeneity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 31(3):1268–1280.

15. van Niekerk A, Berglund J, Sprenger T Norbeck O, Avventi E, Rydén H, Skare S. Control of a wireless sensor using the pulse sequence for prospective motion. Magn Reson Med 2022 Feb;87(2):1046-1061.

16. Biondetti E, et al. Spatiotemporal changes in substantia nigra neuromelanin content in Parkinson’s disease. Brain: J. Neurol. 2020;143:2757–2770.

17. Kim, J. M. et al. Loss of substantia nigra hyperintensity on 7 Tesla MRI of Parkinson’s disease, multiple system atrophy, and progressive supranuclear palsy. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 26, 47–54 (2016).

18. Liu J, van Gelderen P, de Zwart JA, Duyn JH. Reducing motion sensitivity in 3D high-resolution T2*-weighted MRI by navigator-based motion and nonlinear magnetic field correction. Neuroimage. 2020;206:116332.

Figures