1393

Neuromelanin MRI using 2D GRE and deep learning: considerations for improving the visualization of substantia nigra and locus coeruleus1Radiology and nuclear medicine, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, Netherlands, 2Department of Neurology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, Netherlands, 3Department of Imaging Physics, TU Delft, Delft, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Parkinson's Disease, Normal development

An optimized clinically feasible neuromelanin MRI imaging protocol for visualising the SN and LC simultaneously using deep learning reconstruction is presented. For a 2D sequence we set out to optimize the flip-angle for optimal combined SN and LC depiction. We also experimented with combinations of anisotropic and isotropic in-plane resolution, partial vs full echoes and the number of averages. Phantom and in-vivo experiments on three healthy volunteers illustrate that high-resolution imaging combined with deep-learning denoising shows good depiction of the SN and LC with a clinically feasible sequence of 7 minutes.Introduction

Neuromelanin (NM) is a dark pigment found in dopaminergic neurons particularly in the substantia nigra (SN) and locus coeruleus (LC). Visualising NM using MRI is possible with MT-weighted gradient-echo or fast-spin-echo sequences, and has diagnostic value for Parkinson’s Disease (1-3) atypical parkinsonisms (4) and possibly schizophrenia (5). MR imaging of neuromelanin in a clinically feasible scan time can be challenging due to SNR constraints, especially when imaging the LC which is a thin rod-shaped structure in the brainstem.We optimize simultaneous visualisation of the SN and LC using an MT-weighted 2D gradient-echo sequence by varying acquisition and deep learning reconstruction parameters.

Methods

We categorized the sequence optimization in three experiments- Flip-angle optimization using relaxometry

- Balancing SNR and resolution

- Usage of deep learning reconstruction

Flip-angle optimization

SPGR signal calculations were used with relaxometry values for proton density (PD), T1 and T2* from a similar study (7) for tissues (SN + anterior tissue as reference, LC + surrounding gray matter as reference, and CSF) to predict the flip angle which maximized contrast.

Balancing SNR and resolution

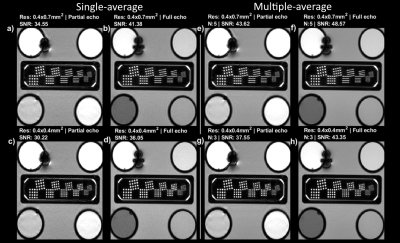

Phantom and in-vivo experiments were used to unfold parameters which affect SNR. A system phantom was scanned coronally at a resolution inset with structures ranging from 0.8-0.4mm (CaliberMRI, Boulder, CO, USA). A single-average experiment aimed to untangle the effect of partial vs full echo (TE=4.0 vs 7.5ms) and (an-)isotropic imaging (0.4x0.7mm2 vs 0.4x0.4mm2) with FA=50o and TR=340ms. SNR was approximated using the standard deviation in a homogenous region of interest. The comparison is biased towards the longer isotropic full-echo acquisition and thus in a second experiment isotropic imaging with 3 averages was compared against anisotropic with 5 averages, approximately time-matched if TR were minimized. For in-vivo experiments only the second experiment was repeated.

Deep-learning reconstruction

A recently available vendor-based deep-learning reconstruction performs denoising and resolves Gibbs ringing artifacts (8). All acquisitions were acquired with Air Recon DL (setting high) and original images free from deep-learning reconstruction were saved.

Results

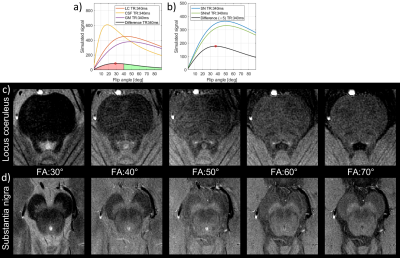

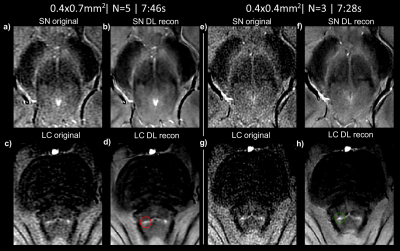

Figure 1 shows the signal calculations for the simulated tissues along with difference curves $$$(SN-SN_{anterior} ; LC-LC_{gray-matter})$$$ with a marked maximum value. For TE=7.5ms and TR=340ms, the theoretical optimal flip angles were 37 and 29 degrees for the SN and LC respectively. For the SN, this corresponded with our in-vivo findings, but when imaging the LC at this flip angle the resulting high CSF signal from the adjacent ventricle renders visualising the LC challenging, and a flip-angle of 50 degrees was preferable.Figure 2 shows phantom data for the single (2a-d) and multiple-averages experiments (2e-h). Acquiring full versus partial echoes in single-average experiments increases SNR 20%, for both isotropic and anisotropic acquisition. When using multiple averages, full echoes increase SNR a 15% for a 13% time increase, and full echoes reduce susceptibility artifacts. Anisotropic-resolution improves SNR but shows partial volume effects of the dot-like LC along the long axis (phase-encoding direction) of the voxel, while isotropic imaging depicts dots more precisely.

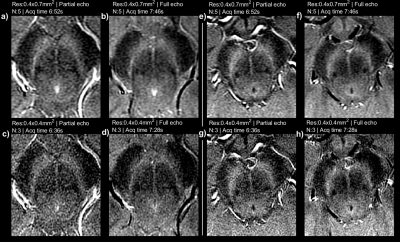

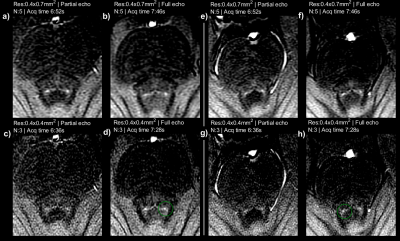

Figures 3 and 4 shows in-vivo results for SN and LC respectively for approximately time-matched acquisitions. Isotropic resolution and 3 averages performs similarly to anisotropic-resolution (using 5 averages (7:46 vs 7:28 min, full echoes). The LC is well depicted as a dot in the isotropic resolution images, corresponding with phantom data.

Figure 5 shows vendor-based deep-learning reconstructed images for anisotropic and isotropic resolution images with full echoes. Denoising improves image quality without accidental blurring, however cannot resolve partial volume effects. DL-based denoising seems to improve all images, and in particular the isotropic resolution images which suffer more from SNR.

Discussion

We conducted a series of phantom and in-vivo experiments to optimize neuromelanin imaging, with regard to optimal contrast, SNR and reconstruction for a clinically feasible acquisition time. When 2D imaging the SN and LC simultaneously, a flip-angle around 35 degrees would be optimal, but the high CSF signal complicates delineation of the adjacent LC. Imaging at a higher flip-angle of 50 degrees is a good compromise, even though not being the optimal flip-angle for imaging either the SN or LC.Figures 2, 3 and 4 show a detailed comparison of partial vs full echoes, and acquiring with anisotropic vs isotropic resolution. Partial echo results in noisier images without significant time-saving. For imaging the SN, either isotropic or anisotropic perform well, however the LC is better depicted as a dot with isotropic imaging.

Deep-learning based denoising improves image quality but cannot resolve partial volume effects. As partial volume effects are more pronounced in anisotropic imaging, a favourable combination is to combine high-resolution isotropic in-plane imaging with denoising.

Future work should reproduce our findings in more subjects. Fluid-attenuation techniques could reduce CSF signal to operate at optimal flip-angles.

Conclusion

Imaging with full echoes and isotropic resolution improves LC depiction. Combining with deep-learning denoising increases SNR. Flip-angle should be optimized relative to TR to avoid CSF signal.Acknowledgements

This project was funded by Erasmus MC – TU Delft Convergence for health and technology.

This project was sponsored by a research grant from Parkinson NL.

References

1. Sasaki M, Shibata E, Tohyama K, Takahashi J, Otsuka K, Tsuchiya K, Takahashi S, Ehara S, Terayama Y, Sakai A. Neuromelanin magnetic resonance imaging of locus ceruleus and substantia nigra in Parkinson's disease. Neuroreport 2006;17(11):1215-1218.

2. Sulzer D, Cassidy C, Horga G, Kang UJ, Fahn S, Casella L, Pezzoli G, Langley J, Hu XP, Zucca FA, Isaias IU, Zecca L. Neuromelanin detection by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and its promise as a biomarker for Parkinson's disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2018;4:11.

3. Jin L, Wang J, Wang C, Lian D, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Lv M, Li Y, Huang Z, Cheng X, Fei G, Liu K, Zeng M, Zhong C. Combined Visualization of Nigrosome-1 and Neuromelanin in the Substantia Nigra Using 3T MRI for the Differential Diagnosis of Essential Tremor and de novo Parkinson's Disease. Front Neurol 2019;10:100.

4. Ohtsuka C, Sasaki M, Konno K, Kato K, Takahashi J, Yamashita F, Terayama Y. Differentiation of early-stage parkinsonisms using neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014;20(7):755-760.

5. Cassidy CM, Zucca FA, Girgis RR, Baker SC, Weinstein JJ, Sharp ME, Bellei C, Valmadre A, Vanegas N, Kegeles LS, Brucato G, Kang UJ, Sulzer D, Zecca L, Abi-Dargham A, Horga G. Neuromelanin-sensitive MRI as a noninvasive proxy measure of dopamine function in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116(11):5108-5117.

6. Wengler K, Cassidy C, van der Pluijm M, Weinstein JJ, Abi-Dargham A, van de Giessen E, Horga G. Cross-Scanner Harmonization of Neuromelanin-Sensitive MRI for Multisite Studies. J Magn Reson Imaging 2021;54(4):1189-1199.

7. Liu Y, Li J, He N, Chen Y, Jin Z, Yan F, Haacke EM. Optimizing neuromelanin contrast in the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus using a magnetization transfer contrast prepared 3D gradient recalled echo sequence. Neuroimage 2020;218:116935.

8. Marc Lebel R. Performance characterization of a novel deep learning-based MR image reconstruction pipeline. arXiv 2020.

Figures