1384

Therapy of Parkinson’s Disease Related Motor and Cognitive Decline with Deep Brain Stimulation of Nucleus Accumbens1Department of Biomedical Engineering, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2PhD Program in Medical Neuroscience, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan, 3Department of Neurology, Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, Hualien, Taiwan, 4Department of Neurology, School of Medicine, Tzu Chi University, Hualien, Taiwan

Synopsis

Keywords: Parkinson's Disease, Parkinson's Disease

The progression of Parkinson′s disease (PD) is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, and deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the nucleus accumbens (NAc) was found to enhance mitochondrial function. Therefore, the presented study aimed to explore the therapeutic effects of NAc-DBS on PD. In this study, the NAc-DBS treatment, behavioral tests, brain magnetic resonance imaging analysis, and mitochondrial respiratory assay were conducted on the MitoPark PD mouse model. After NAc-DBS, the PD mouse model showed improvements in motor and cognitive functions with increased functional connectivity and promoted aerobic metabolism in the dopaminergic (DA) pathways.Introduction

Mitochondrial abnormalities and progressive degeneration in dopaminergic (DA) neurons are implicated in the pathophysiology of Parkinson′s disease (PD)1. For reducing movement disorders of PD, deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a common surgical treatment through mediating the basal ganglia loops involving motor, cognitive, and limbic functions2,3. Moreover, clinical studies have shown positive results of DBS in the treatment of mitochondrial disorders4. A rodent study revealed DBS of the nucleus accumbens (NAc) increased mitochondrial respiration in the prefrontal cortex5. NAc is a key DA terminal region in the mesolimbic pathway receiving dopamine inputs from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and involves in reward processing and aversion6. Besides, NAc integrates information from limbic and cortical regions, including the ventral hippocampus (vHIPP) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC)7,8. In addition, mPFC of the mesocortical pathway is also innervated by DA neurons originating in the VTA, and essential in executive and cognitive functions6. Currently, NAc-DBS has been investigated for the treatment of depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder9, while the impacts on metabolic functions and behaviors in PD still remain unclear. In the present study, a genetic MitoPark PD mouse model with mitochondrial dysfunction was applied10. Furthermore, we conducted NAc-DBS treatment, behavioral investigations, resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning, and respiratory assay to investigate the therapeutic effects of NAc-DBS.Methods

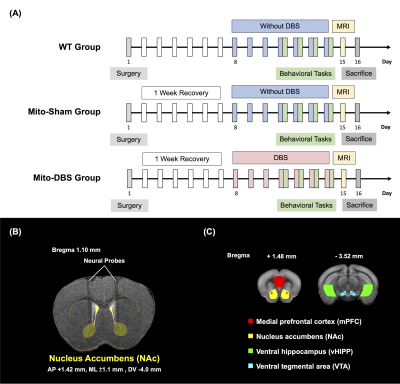

To investigate NAc-DBS therapeutic effects, 20-week-old male experimental animals were divided into three groups: wild-type (WT) group (C57BL/6 mice), Mito-Sham group (MitoPark mice), and Mito-DBS group (MitoPark mice) (N = 5, each group). Mice were housed in animal facility with controlled temperature at 21–24°C and 12:12-h light/dark cycle. The experimental design was shown in Figure 1A. All animals were conducted with bilateral NAc probes implantations (AP: + 1.42 mm, ML: ± 1.1 mm, DV: − 4.0 mm) (Figure 1B). The Mito-DBS group was applied with bilateral intermittent theta-burst NAc-DBS stimulation for 30 mins per day (intensity 150 μA, pulse width 100 μs, pulse frequency:200 Hz, burst width 100ms, inter burst interval 100ms). Open field test (OFT), novel object recognition task (NOR), and T-maze task were used to evaluate locomotor, long-term recognition memory, and working memory, respectively11-13. In the OFT, mice were allowed to uninterrupted explore the open field maze for 10 mins, and the total distance were analyzed by OptiMouse program14. NOR was performed for continuous three days, containing habituation day, training day, and testing day, and preference index (PI) was calculated as the memory performance. Mice in T-maze tends to choose the arm not visited before, reflecting spontaneous alternation. Whole-brain resting-state functional MRI was obtained from a 7 Tesla Bruker MRI system (Bruker Biospec 70/30 USR, Ettlingen, Germany) using gradient-echo planar imaging (GE-EPI) sequence with following parameters: repetition time = 2,000 ms, echo time = 20 ms, 14 coronal slices, slice thickness = 0.5 mm, field of view = 20 × 20 mm2, matrix size = 80 × 80, and bandwidth = 200 kHz. According to Allen mouse atlas15, region of interests (ROIs) included mPFC, NAc, vHIPP, and VTA (Figure 1C). Functional connectivity (FC) was analyzed and visualized with significant results using a one sample t test (thresholds: p < 0.05 and cluster size > 200 voxels) by the FMRIB Software Library v5.0 (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) and the analysis of functional neuroimages software (http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni). After sacrifice, oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) was measured by a respiratory assay (Seahorse XF Analyzer, Agilent) according to previously published methods16. Statistical analyses were performed with Kruskal–Wallis test and post-hoc analysis with Dunn’s test among multiple groups. Significance was inferred at p-value < 0.05. All data were presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean.Results

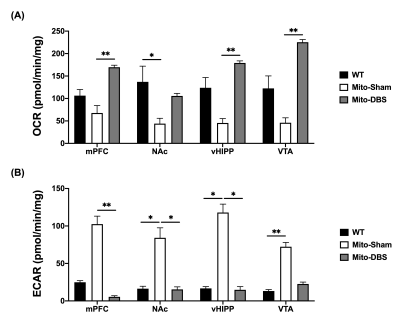

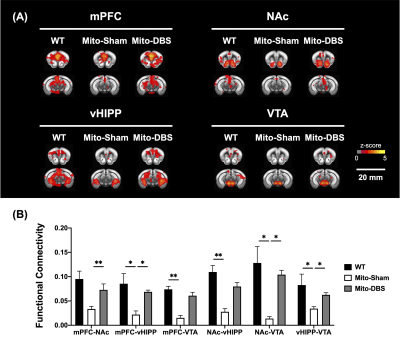

In behavioral tasks, significantly higher total distance, PI value, and T-maze correct ratio were observed in Mito-DBS group compared with Mito-Sham group (Figure 2). After seven days of NAc-DBS, Mito-DBS group showed improved FC in mPFC, NAc, vHIPP, and VTA (Figure 3). For ATP production, there were more OCR and less ECAR in Mito-DBS group, compared to Mito-Sham group (Figure 4).Discussion

In the present study, we applied a PD mouse model to explore the effects of NAc-DBS on behavioral abilities, brain networks, and metabolic functions. After NAc-DBS treatment, the motor and cognitive impairments in MitoPark mice were improved, which also corresponded to the enhancement of FC between the DA pathways. These findings were consistent with the previous studies that showed NAc-DBS could modulate neuronal activity within prefrontal and limbic regions that underlie cognition and behavior17-19. Moreover, we also found that NAc-DBS could increase oxygen consumption to promote aerobic metabolism over glycolysis in the DA pathways. DBS has been demonstrated to promote neuroprotection by increasing the expression of neurotrophic molecules, which can further modify energic metabolic20,21.Conclusion

This study showed that NAc-DBS treatment improved motor and cognitive function in PD mouse models, as well as functional activity and metabolic function in the DA pathways. Our results suggest NAc-DBS in PD has the potential to mitigate metabolic impairment and disease progression.Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by National Science and Technology Council under Contract numbers of MOST 111-2321-B-A49-005-, 111-2314-B-303-026-, 111-2221-E-A49-049-MY2, 111-2314-B-038-059-MY3, and 110-2314-B303-016.

References

1. Ekstrand MI, Terzioglu M, Galter D, et al. Progressive parkinsonism in mice with respiratory-chain-deficient dopamine neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(4):1325-1330.

2. Maiti P, Manna J, Dunbar GL. Current understanding of the molecular mechanisms in Parkinson's disease: Targets for potential treatments. Translational neurodegeneration. 2017;6(1):1-35.

3. Deuschl G, Paschen S, Witt K. Clinical outcome of deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2013;116:107-128.

4. Macdonald R, Barnes K, Hastings C, et al. Mitochondrial abnormalities in Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease: can mitochondria be targeted therapeutically? Biochemical Society Transactions. 2018;46(4):891-909.

5. Kim Y, McGee S, Czeczor JK, et al. Nucleus accumbens deep-brain stimulation efficacy in ACTH-pretreated rats: alterations in mitochondrial function relate to antidepressant-like effects. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(6):e842.

6. Reneman L, VanDer Pluijm M, Schrantee A, et al. Imaging of the dopamine system with focus on pharmacological MRI and neuromelanin imaging. European Journal of Radiology. 2021;140:109752.

7. Pierce RC, Kumaresan V. The mesolimbic dopamine system: the final common pathway for the reinforcing effect of drugs of abuse? Neuroscience & biobehavioral reviews. 2006;30(2):215-238.

8. Isokawa M. Cellular signal mechanisms of reward-related plasticity in the hippocampus. Neural plasticity. 2012.

9. Jakobs M, Fomenko A, Lozano AM, et al. Cellular, molecular, and clinical mechanisms of action of deep brain stimulation—a systematic review on established indications and outlook on future developments. EMBO molecular medicine. 2019;11(4):e9575.

10. Hsieh TH, Kuo CW, Hsieh KH, et al. Probiotics alleviate the progressive deterioration of motor functions in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Sci. 2020;10(4):206.

11. Leger M, Quiedeville A, Bouet V, et al. Object recognition test in mice. Nature protocols. 2013;8(12):2531.

12. Seibenhener ML, Wooten MC. Use of the open field maze to measure locomotor and anxiety-like behavior in mice. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments). 2015(96):e52434.

13. Deacon RM, Rawlins JNP. T-maze alternation in the rodent. Nature protocols. 2006;1(1):7-12.

14. Ben-Shaul Y. OptiMouse: a comprehensive open source program for reliable detection and analysis of mouse body and nose positions. BMC biology. 2017;15(1):1-22.

15. Papp EA, Leergaard TB, Calabrese E, et al. Waxholm Space atlas of the Sprague Dawley rat brain. Neuroimage. 2014;97:374-386.

16. Lai JH, Chen KY, Wu JC, et al. Voluntary exercise delays progressive deterioration of markers of metabolism and behavior in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain research. 2019;1720:146301.

17. Albaugh DL, Salzwedel A, Van Den Berge N, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of electrical and optogenetic deep brain stimulation at the rat nucleus accumbens. Scientific reports. 2016;6(1):1-13.

18. Van Dijk A, Klompmakers AA, Feenstra MG, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the accumbens increases dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenaline in the prefrontal cortex. Journal of neurochemistry. 2012;123(6):897-903.

19. Cho S, Hachmann JT, Balzekas I, et al. Resting‐state functional connectivity modulates the BOLD activation induced by nucleus accumbens stimulation in the swine brain. Brain and behavior. 2019;9(12):e01431.

20. Aum DJ, Tierney TS. Deep brain stimulation: foundations and future trends. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark. 2018;23(1):162-182.

21. Markham A, Cameron I, Bains R, et al. Brain‐derived neurotrophic factor‐mediated effects on mitochondrial respiratory coupling and neuroprotection share the same molecular signalling pathways. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;35(3):366-374.

Figures

Figure 1. Experimental design. (A) To investigate NAc-DBS therapeutic effect on MitoPark mice, three groups, WT group, Mito-Sham group, and Mito-DBS group, were conducted with bilateral NAc probes implantations, behavioral tasks, MRI scan, and respiratory assay. (N = 5, each group) (B) T2-weighted image overlaid with a mouse brain atlas showed the tracks of the neural probes implanted into the bilateral NAc. (C) Chosen ROIs including mPFC (red), NAc (yellow), vHIPP (green), and VTA (blue).

Figure 3. Functional MRI analysis. (A) The cross-correlation maps of each ROIs with whole brain voxels. (B) MitoPark mice showed decreased FC than WT group. After NAc-DBS, Mito-DBS group showed significant restoration of FC compared with Mito-Sham group. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01