1381

Towards Integrating DL Reconstruction and Diagnosis: Meniscal Anomaly Detection Shows Similar Performance on Reconstructed and Baseline MRI1Department of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States, 2Department of Bioengineering, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Joints, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence

Meniscal lesions are a common knee pathology, but pathology detection from MRI is usually evaluated on full-length acquisitions. We trained UNet and KIKI I-Net reconstruction algorithms with several loss function configurations, showing k-space losses are not required to obtain robust reconstructions. We trained and evaluated Faster R-CNN to detect meniscal anomalies, showing similar performance on R=8 reconstructions and fully-sampled images, demonstrating its utility as an assessment tool for reconstruction performance and indicating reconstructed images are viable for downstream clinical postprocessing tasks.

INTRODUCTION

Meniscal lesions represent the leading cause of orthopedic surgical interventions in the United States1. MRI remains among the best non-invasive tests for meniscal anomalies2. Advances in deep learning (DL) have significantly extended the diagnostic capabilities of musculoskeletal imaging. As such, object detection algorithms can assist radiologists in finding abnormalities3,4. Simultaneously, DL reconstruction algorithms have been developed to accelerate MR acquisition, optimizing reconstructions for normalized root mean square error (nRMSE)5, peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR)6, and structural similarity index (SSIM)7. Reconstruction algorithms have been optimized for radiologist image evaluation. However, the utility of reconstructed images for downstream tasks has not been well characterized: namely, how much would deep learning-based object detection, trained on fully-sampled images, performance degrade when evaluated on reconstructed images for clinical applications?METHODS

Image AcquisitionMulti-channel k-space data were acquired for a dataset of 937 3D-Fast-Spin-Echo fat-suppressed CUBE images on the UCSF GE Signa 3T MRI scanner for UCSF clinical population between June 2021 and June 2022. Acquisition parameters were as follows: FOV=15cm2; acquisition matrix=256×256×200; ±62.5kHz readout bandwidth; TR=1002ms; TE=29ms; 4X ARC acceleration8. Training and validation dataset sizes for reconstruction were 220/58 patients and 750/129 for object detection. A shared test set of 58 patients was used for both algorithms.

Undersampling and Pre-Processing

For reconstruction, 3D multicoil k-space was 8X undersampled in ky-kz with a center-weighted Poisson pattern while fully sampling the 5% central square in k-space. Undersampled and fully-sampled k-space were 1D inverse Fourier transformed along the slice direction, yielding undersampled and corresponding ground truth kx-ky-z 2D k-space for each coil. Root sum of squares coil combination of fully sampled coil images was used to calculate ground truth coil-combined images.

Anomaly Annotation

Annotation was performed using an online web platform (MD.ai New York, New York). Three radiologists manually inspected and annotated 937 3D volumes (183,652 2D slices) for meniscal lesions, delineating 17,509 bounding boxes. Meniscus masks were generated from an in-house DL segmentation pipeline9. Slices containing healthy meniscus were selected by running connected components analysis on meniscus masks, removing clusters with fewer than 20 pixels, and dropping clusters overlapping with anomaly boxes.

Reconstruction of Accelerated Images

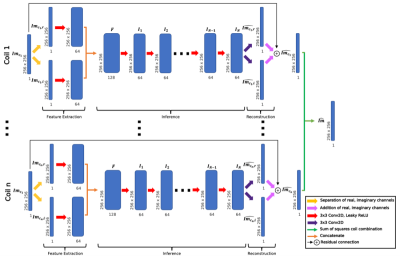

Two reconstruction models were trained: UNets and KIKI-style I-Nets (Fig. 1). 4 versions of each were trained with the following loss functions: (1) coil-combined SSIM loss; (2) coil-combined L1 and SSIM loss; (3) multi-coil k-space and coil-combined SSIM loss; (4) coil-combined L1 and SSIM and multi-coil k-space loss. All configurations were trained for 15 epochs with a learning rate of 0.001.

Object Detection Training

The object detection dataset contained slices with healthy meniscus and/or anomaly bounding boxes. A Faster R-CNN with a ResNet-50-FPN backbone model10 was trained on 2D slices for 20 epochs with a learning rate of 0.01 and batch size of 16. Precision-Recall (PR) curves were plotted for each evaluated model after applying a 0.3 Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold on predictions to determine the optimal confidence threshold. Predictions with scores below the selected confidence threshold were dropped. Precision, recall, mean Average Precision (mAP), and F1-score were calculated.

RESULTS

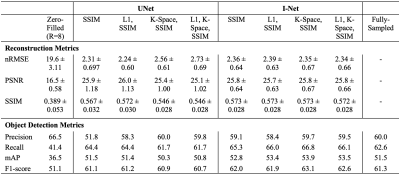

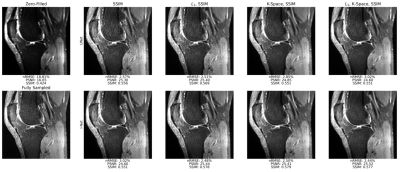

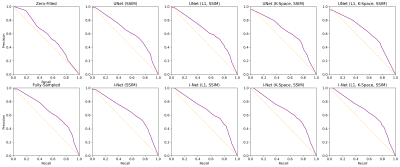

Reconstruction metrics for models trained with all loss functions are in Fig. 2, with an example reconstructed slice in Fig. 3. Reconstruction metrics show no to limited improvement when using a k-space data consistency loss term during training, and while not reflected in metrics, I-Net pipeline is superior to UNet in removing undersampling aliasing artifacts. Faster R-CNN performed with 66.1 precision, 67.5 recall, 58.5 mAP, 66.8 F1-score on validation, and 61.2 precision, 65.9 recall, 53.8 mAP, and 63.5 F1-score on test datasets. A confidence threshold of 0.75 was selected for the final metrics calculation. Object detection metrics are summarized in Fig. 2, and corresponding PR curves are shown in Fig. 4, with target and predicted bounding boxes demonstrated in Fig. 5. Zero-filled reconstruction had the lowest recall, mAP, and F1-score, but the performance was closer to baseline metrics for all other reconstructions.DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

k-Space loss functions have seen increased prominence in training DL reconstruction models, but our work shows their inclusion may not be required to attain high-quality reconstruction performance. Moreover, several studies have shown standard reconstruction metrics not to correlate with radiologist annotations11, and our reconstruction performance confirms this, as the I-Net's improved aliasing artifact removal compared to the UNet was not captured by reconstruction metrics. Interestingly, object detection metrics may be a powerful alternative, as the Faster R-CNN detected meniscal anomalies with better recall without impairing precision for I-Net reconstructed images compared to UNet, suggesting I-Net artifact removal could be better captured in object detection metrics. Encouragingly, however, precision, recall, mAP, and F-1 score metrics for I-Net and some UNet models indicated very comparable meniscal anomaly detection to fully sampled images, even at R=8, indicating properly trained reconstruction algorithms can generate images robust enough for downstream tasks, and that properly trained image postprocessing algorithms can generalize to what is likely slightly out-of-distribution reconstructed images.Our work demonstrates object detection algorithms see a limited reduction in performance when evaluated on R=8 reconstructed images as opposed to ground truth and reveals their utility as an assessment tool for reconstruction performance. Future object detection directions may include loss function tuning and investigation of alternate pathologies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Madeline Hess for providing technical support. The project was supported by NIH R01AR078762.References

1. Murphy CA, Garg AK, Silva-Correia J, Reis RL, Oliveira JM, Collins MN. The Meniscus in Normal and Osteoarthritic Tissues: Facing the Structure Property Challenges and Current Treatment Trends. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2019 Jun 4;21:495-521. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-060418-052547. Epub 2019 Apr 8. PMID: 30969794.

2. Trunz LM, Morrison WB. MRI of the Knee Meniscus. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2022 May;30(2):307-324. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2021.11.009. Epub 2022 Apr 13. PMID: 35512892.

3. Bayramoglu N, Nieminen MT, Saarakkala S. Automated detection of patellofemoral osteoarthritis from knee lateral view radiographs using deep learning: data from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST). Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2021 Oct;29(10):1432-1447. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2021.06.011. Epub 2021 Jul 8. PMID: 34245873.

4. Roblot V, Giret Y, Bou Antoun M, Morillot C, Chassin X, Cotten A, Zerbib J, Fournier L. Artificial intelligence to diagnose meniscus tears on MRI. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2019 Apr;100(4):243-249. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2019.02.007. Epub 2019 Mar 28. PMID: 30928472.

5. Fienup JR. Invariant error metrics for image reconstruction. Appl Opt. 1997 Nov 10;36(32):8352-7. doi: 10.1364/ao.36.008352. PMID: 18264376.

6. Horé A, Ziou D. Is there a relationship between peak-signal-to-noise ratio and structural similarity index? IET Image Processing. 2013;7:12-24.

7. Wang Z, Bovik AC, Sheikh HR, Simoncelli EP. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2004 Apr;13(4):600-12. doi: 10.1109/tip.2003.819861. PMID: 15376593.

8. Brau AC, Beatty PJ, Skare S, Bammer R. Comparison of reconstruction accuracy and efficiency among autocalibrating data-driven parallel imaging methods. Magn Reson Med. 2008 Feb;59(2):382-95. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21481. PMID: 18228603; PMCID: PMC3985852.

9. Nunes BAA et al. MRI-based multi-task deep learning for cartilage lesion severity staging in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27:S398-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2019.02.399

10. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017 Jun;39(6):1137-1149. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. Epub 2016 Jun 6. PMID: 27295650.

11. Mason A, Rioux J, Clarke SE, Costa A, Schmidt M, Keough V, Huynh T, Beyea S. Comparison of Objective Image Quality Metrics to Expert Radiologists' Scoring of Diagnostic Quality of MR Images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2020 Apr;39(4):1064-1072. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2019.2930338. Epub 2019 Sep 16. PMID: 31535985.

Figures

Fig. 1: I-Net architecture predicts coil-combined images from undersampled multicoil image-space. Undersampled images were fed through feature extractors for real and imaginary channels, inference convolutions (N=10), and a reconstruction convolution, then sum of squares combined to yield single-coil predictions. A similarly structured UNet architecture was also trained, replacing the feature extractor, inference, and reconstruction convolutions with a UNet; weights were shared across coils for both.

Fig. 2: Reconstruction metrics show improved reconstructions over R=8 zero-filled initializations, regardless of loss function. I-Net performance was similar regardless of training loss, and UNet performance declined with k-space loss inclusion. Object detection metrics demonstrate similar performance on reconstructed and baseline images, with I-Net showing stronger recall. K-space losses may not be nececessary for optimal reconstruction, and anomaly detection showed little performance decline at R=8.

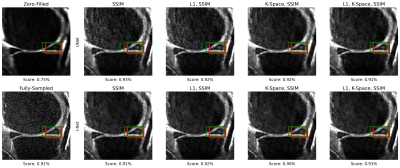

Fig. 3: Sample sagittal slice reconstructions for UNet and I-Net pipelines trained all 4 loss functions at R=8 show strong fidelity to ground truth. Though not reflected well in reconstruction metrics, I-Net pipelines better mitigate aliasing artifacts than corresponding UNet pipelines. Reconstructed images see very limited improvement in sharpness and fine detail retention when k-space data consistency loss function is used, showing it may not be required to obtain high-quality reconstructions.

Fig. 4: Precision-Recall Curves show a similar performance of the object detection model on all reconstructed images except zero-filled, which has a significantly lower recall. These results further characterize the object detection algorithms as suitable for potential assistance in reconstruction performance control. The optimal prediction confidence threshold of 0.75 was obtained from a baseline curve and used in all other detection metric calculations.

Fig. 5: An example of meniscal anomaly detection for a sagittal slice. The target bounding box containing the meniscal anomaly is depicted in red, and the predicted bounding box is in green. In this case, the object detection model shows good performance on all reconstructed slices. Zero-filled reconstructed slice has lower confidence for the same anomaly, which is consistent with the other detection metrics observed.