1380

Uncertainty maps for training a deep learning model that automatically delineates the skeleton from Whole-Body Diffusion Weighted Imaging1The Institute of Cancer Research, London, United Kingdom, 2Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Mint Medical, Heidelberg, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Segmentation

Whole-Body Diffusion Weighted Imaging (WBDWI) requires automated tools that delineate malignant bone disease based on high b-value signal intensity, leading to state-of-the-art imaging biomarkers of response. As an initial step, we have developed an automated deep-learning pipeline that automatically delineates the skeleton from WBDWI. Our approach is trained on paired examples, where ground truth is defined through a set of weak labels (non-binary segmentations) derived from a computationally expensive atlas-based segmentation approach. The model showed on average a dice score, precision and recall between the manual and derived skeleton segmentations on test datasets of 0.74, 0.78, and 0.7, respectively.Background

Whole-Body Diffusion Weighted Imaging (WBDWI) is an established technique for staging and non-invasive response assessment of bone disease in patients with Advanced Prostate Cancer (APC) and Multiple Myeloma (MM)1,2. This technique can measure the Total Disease Volume (TDV, in millilitres) and the Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC), as potential response biomarkers to systemic treatments3. However, at present this still requires tedious manual delineation of disease, requiring approximately 1-2 hours of clinician time per patient, depending on the disease volume4. Automated disease delineation tools are thus highly desirable and a logical first step to achieve this would be delineation of the full patient skeleton. Supervised deep learning algorithms show excellent performance for segmentation tasks, but typically consume large amounts of training data consisting of manual segmentations that are not available to WBDWI. We have developed an automated pipeline for deriving full-skeleton annotations on WBDWI using computationally expensive atlas-based segmentations to derive “weak labels”, that may in turn be used to train a much faster supervised deep learning model. Furthermore, this approach intrinsically produces estimates of skeletal segmentation uncertainty that may be used for improved model interpretability.Methods

Patient PopulationFor training the deep learning model two retrospective WBDWI cohorts were used: 200 patients diagnosed with APC (Cohort A) and 46 patients diagnosed with MM (Cohort B). Every patient from the APC cohort underwent baseline and post-treatment scans acquired at one of three imaging centres (169/22/9 patients per centre). Patients with confirmed MM underwent a baseline scan at one of two imaging centres (32/14 patients per centre). Patient data from datasets A and B were split into training and validation (80:20) cohorts.

Image Acquisition

WBDWI scans were acquired using two (50/900 s/mm2) or three (50/600/900 s/mm2) b-values on a 1.5T scanner (MAGNETOM Aera/Avanto, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany), over 4-5 stations from the skull base to mid-thigh (APC) or skull vertex to knees (MM), with each station comprising 40 slices. Echo-planar image acquisition was used (GRAPPA=2) with a double-spin echo diffusion encoding scheme applied over three orthogonal encoding directions.

Development of AI-driven model on WBDWI

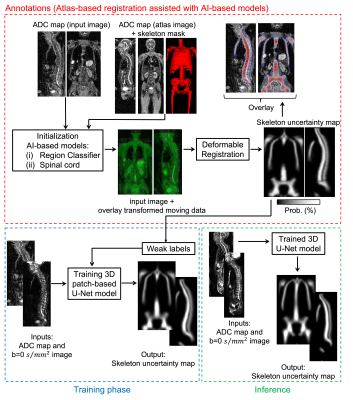

Figure 1 shows the automated pipeline for annotations, training and inference of the deep learning model that delineates the skeleton from WBDWI.

- Annotations

- Training

Results

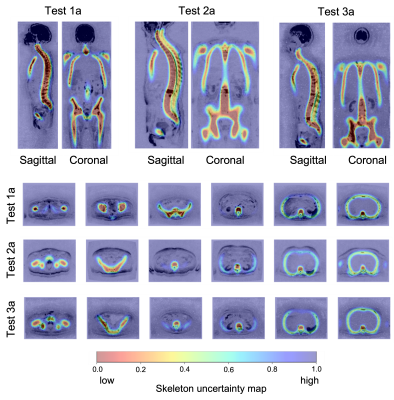

Figure 2 shows the skeleton uncertainty maps derived from the U-Net model for three cases in the validation dataset. Voxels classified with low and high uncertainty aligned with the patient skeleton and soft tissue background, respectively.The inference time of the trained U-Net model was within 5 seconds with improvement in speed over the atlas-based registration of 97.92%.

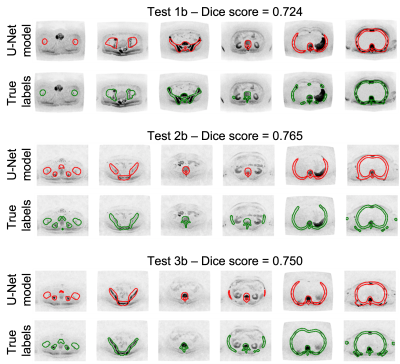

To quantitatively assess the accuracy of the U-Net model, the skeleton uncertainty maps for all the images in the atlas cohort (Cohort C) were derived. A threshold of 0.45 was applied to derive a skeleton mask. The mean dice score, precision and recall between the manual and derived skeleton mask were 0.74, 0.78, and 0.7, respectively.

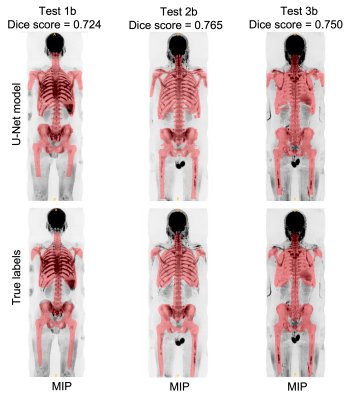

Skeleton masks were transferred into the ADC map to derive the ADC statistics and volume within the delineated regions. The relative error of median ADC and volume between manual and automated methods was 3.27% and 10.9%, respectively.

Figures 3 and 4 show manual and derived skeleton masks superimposed on axial and Maximum-Intensity-Projection (MIP) of b=900 s/mm2 images for three cases in the atlas cohort.

Discussion

We have developed a 3D U-Net model to automatically delineate the skeleton from WBDWI. The model was trained using uncertainty maps from an automated annotations phase. Our model showed similar performance to algorithms that perform skeleton segmentation from high-resolution and high SNR images (CT, T1w and T2w) published in the literature6-8. This approach appears useful for the towards development of bone disease segmentation.The quantitative analysis was performed using the atlas cohort which was also used for generating the weak labels. This might be seen as a potential weakness but the original images from the atlas cohort were not used directly for training. Therefore, we argue that these results form a valid test.

Acknowledgements

This project is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research [i4i grant II- LA-0216-20007 part of the NIHR]. The authors would like to acknowledge Mint Medical®References

1. A. R. Padhani et al., “METastasis Reporting and Data System for Prostate Cancer: Practical Guidelines for Acquisition, Interpretation, and Reporting of Whole-body Magnetic Resonance Imaging-based Evaluations of Multiorgan Involvement in Advanced Prostate Cancer,” Eur. Urol., vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 81–92, 2017

2. C. Messiou et al., “Guidelines for Acquisition, Interpretation, and Reporting of Whole-Body MRI in Myeloma: Myeloma Response Assessment and Diagnosis System (MY-RADS),” Radiology, vol. 291.1, no. 7, 2019.

3. R. Perez-Lopez et al., “Diffusion-weighted imaging as a treatment response biomarker for evaluating bone metastases in prostate cancer: A pilot study,” Radiology, vol. 283, no. 1, pp. 168–177, 2017

4. M. D. Blackledge et al., “Inter- and Intra-Observer Repeatability of Quantitative Whole-Body, Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (WBDWI) in Metastatic Bone Disease,” PLoS One, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 1–12, 2016

5. A. Candito, M. D. Blackledge, R. Holbrey, and D. M. Koh, “Automated tool to quantitatively assess bone disease on Whole-Body Diffusion Weighted Imaging for patients with Advanced Prostate Cancer,” in Medical Imaging with Deep Learning, 2022, pp. 2–4.

6. H. Arabi and H. Zaidi, “Comparison of atlas-based techniques for whole-body bone segmentation,” Med. Image Anal., vol. 36, pp. 98–112, 2017

7. I. Lavdas et al., “Fully automatic, multiorgan segmentation in normal whole body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), using classification forests (CFS), convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and a multi-atlas (MA) approach,” Med. Phys., vol. 44, no. 10, pp. 5210–5220, 2017

8. J. Ceranka et al., “Multi-atlas segmentation of the skeleton from whole-body MRI—Impact of iterative background masking,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 83, no. 5, pp. 1851–1862, 2019

Figures