1379

Predicting Gestational Age at Birth in the Context of Preterm Birth Using Comprehensive Fetal MRI Acquisitions1School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Department of Women & Children's Health, Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom, 3Department of Perinatal Imaging & Health, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 4Department of Biomedical Engineering, King's College London, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence

The accurate prediction of preterm birth is a clinically crucial but challenging problem due to its complex aetiology. In this work, data from fetal anatomical and functional multi-organ MRI acquisitions are used to train Random Forests and Support Vector Machines to predict gestational age at delivery. These predictions are classified as 'term' or 'preterm'. The model with highest sensitivity, a Random Forest, achieved 0.85 sensitivity, 0.81 accuracy, 0.8 specificity, 1.99 weeks Mean Absolute Error, and 0.58 R2 score. This work proves the potential of Machine Learning models trained on anatomical and functional MRI data to predict gestational age at delivery.Introduction

Preterm birth is defined as live births that occur before 37 weeks gestation1. The global preterm birth rate is around 11% of all births2, including medically induced and spontaneous preterm birth. Complications associated with preterm birth are the leading cause of neonatal mortality and mortality among children aged under 5 years3. While there has been a continuous rise in survival rates of preterm babies over the last 30 years4,5, it has not translated into a decrease of short- or long-term morbidity6-8.Furthermore, the aetiologies underlying preterm birth are complex and poorly understood9, contributing to the lack of a universal test to predict preterm birth10. A reliable model that could predict the timing of delivery of a baby would have important benefits such as ensuring women are transferred to appropriate neonatal care facilities, and adequately timing therapies to reduce neonatal mortality and morbidity11. Most studies to date focus on parameters such as ultrasound-derived cervical length or cervicovaginal fluid biomarkers such as fetal fibronectin12-14. While approaches increasingly leverage the high-resolution and quantitative advantages of MRI11,15 , these remain focused on individual organs only, not matching the complex aetiology of preterm birth. The objective of this work is therefore to explore the potential of comprehensive fetal MRI acquisitions combined with supervised machine learning (ML) models to predict gestational age (GA) at birth.

Methods

Data AcquisitionData from 287 pregnancies were obtained as part of nine fetal research studies. For each patient, an MR scan and a time-matched growth ultrasound were acquired, along with a routine clinical anomaly scan at 20 weeks GA. Medical history and pregnancy outcomes were also recorded. The MR scans were performed on a clinical 3T Philips Achieva MRI scanner.

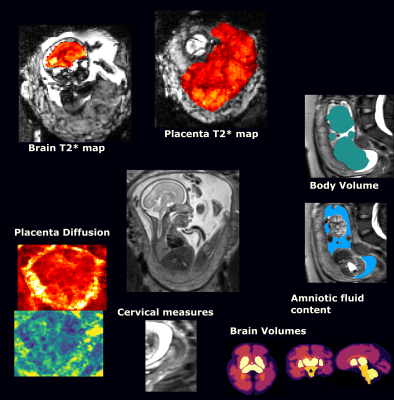

Structural and functional measurements such as cervical length, foetal head circumference, or mean T2* value of the placenta (see Figure 1) were obtained from the MRI and ultrasound data by experienced clinicians. A dataset containing these features, alongside medical history and pregnancy outcome of each patient was used to develop the models.

Data Pre-processing

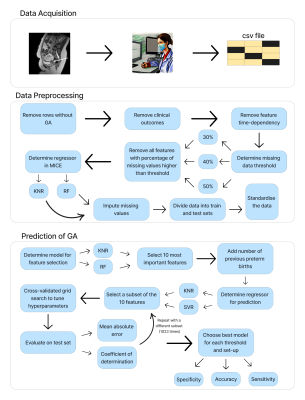

The first step was to remove subjects lacking a recording of GA at delivery. This left a total of 239 patients. Next, every outcome measure was removed from the feature set since these measures are registered after delivery. Time-dependent measurements such as cervical length were standardised using the method of internally studentised residuals16.

Missing data was imputed using the MICE algorithm17, wherein missing values were regressed iteratively from the available features. Two models were investigated to perform the regression within the MICE algorithm: Weighted K-Nearest Neighbours (KNN) and Random Forest (RF). In addition, three different thresholds for missing data were considered (see Figure 2), starting at 30% to include clinically important features, up to 50% which is the highest threshold usually encountered in the literature18.

The data were split into train and test sets with a 4:1 ratio, keeping an equal preterm:term ratio. The training and test sets were standardised with respect to the training set.

Prediction of GA

The two regressors investigated to predict GA at delivery were Support Vector Regression (SVR) and RF due to their ability to capture nonlinear relationships. Before training these models, ten features most predictive of GA were selected based on feature importance obtained by Linear Regression (LR) or RF. If the number of previous preterm births was not one of the selected features, the tenth feature was replaced by it due to its wide availability and clinical importance10,19. The RF and SVR were trained with every non-empty subset of the selected features as input. The hyperparameters for each of these models were tuned with respect to the R2 score20 using a cross-validated grid search21.

The metrics used for evaluating the models on the test set were the R2 score and the mean absolute error (MAE). The predictions of each model were labelled as ‘term’ or ‘preterm’ and accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity are measured. Figure 2 illustrates the workflow of the project.

Results

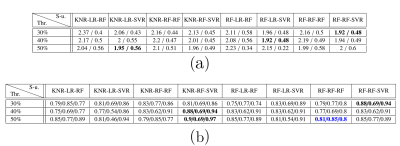

Figure 3 displays the metrics obtained by the best performing models for each missing data threshold and set-up (defined as a sequence of imputation, feature selection, and prediction models) combination. The predictions made by the models with the highest accuracy per threshold are depicted in Figure 4, alongside the predictions of the best model with highest sensitivity.Figure 5 shows tallies of the number of times each feature was used by the models in Figure 3. Cervical length and placental T2* measurements are consistently used by the best models.

Discussion

The most used features by the best models are in line with the literature, with cervical length being an example consistently used in clinical practice10,19. Placental features obtained from MR scans were other prominent features, which is in line with the current understanding of the mechanisms leading to preterm birth22.Conclusion

This work demonstrates the potential for ML models trained on multimodal MRI data to predict which fetuses are most at risk of preterm birth during gestation. Furthermore, the identification of the most relevant quantities, e.g. the selection of mean placental T2* in 83.3% of the best models, allows to target future acquisition protocols even more specifically.Acknowledgements

Fajardo-Rojas would like to acknowledge funding from the EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Smart Medical Imaging (EP/S022104/1). This work was supported by supported by the Wellcome Trust, the NIH Human Placenta Project grant 1U01HD087202-01 (Placenta Imaging Project (PIP)), a Wellcome Trust Sir Henry Wellcome Fellowship [201374/Z/16/Z] and a UKRI FLF [MR/T018119/1], an NIHR Advanced Fellowship [NIHR3016640] to LS and by core funding from the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering [WT203148/Z/16/Z].References

1. World Health Organization. Preterm birth. Feb. 2018. url: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth.

2. Salimah Walani. “Global burden of preterm birth”. In: International Journal of Gynecology Obstetrics 150 (July 2020), pp. 31–33. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13195.

3. Jamie Perin et al. “Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–19: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals”. In: The Lancet Child Adolescent Health 6 (Nov. 2021). doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00311-4.

4. Hannah Blencowe et al. “National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: A systematic analysis and implications”. In: Lancet 379 (June 2012), pp. 2162–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4.

5. Saifon Chawanpaiboon et al. “Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis”. In: The Lancet Global Health 7.1 (2019), e37–e46. issn: 2214-109X. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)

30451-0. url: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214109X18304510.

6. Jeanie LY Cheong et al. “Have outcomes following extremely preterm birth improved over time?” In: Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. Vol. 25. 3. Elsevier. 2020, p. 101114.

7. Rosemarie Boland, Jeanie Cheong, and Lex Doyle. “Changes in long-term survival and neurodevelopmental disability in infants born extremely preterm in the post-surfactant era”. In: Seminars in Perinatology 45 (Aug. 2021), p. 151479. doi: 10.1016/j.semperi.2021.151479.

8. Marilee Allen, Elizabeth Cristofalo, and Christina Kim. “Outcomes of Preterm Infants: Morbidity Replaces Mortality”. In: Clinics in perinatology 38 (Sept. 2011), pp. 441–54. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2011.06.011.

9. Heather Frey and Mark Klebanoff. “The epidemiology, etiology, and costs of preterm birth”. In: Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 21 (Jan. 2016). doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2015.12.011.

10. Natalie Suff, Lisa Story, and Andrew Shennan. “The prediction of preterm delivery: What is new?” In: Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 24 (Sept. 2018). doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2018.09.006.

11. Lisa Story et al. “The use of antenatal fetal Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the assessment of patients at high risk of preterm birth”. In: European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 222 (Jan. 2018). doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.01.014.

12. Lisa Story et al. “Foetal lung volumes in pregnant women who deliver very preterm: a pilot study”. In: Pediatric Research 87 (Dec. 2019). doi: 10.1038/s41390-019-0717-9.

13. Danielle Abbott et al. “Quantitative Fetal Fibronectin to Predict Preterm Birth in Asymptomatic Women at High Risk”. In: Obstetrics and gynecology 125 (May 2015), pp. 1168–1176. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000754.

14. S. Radford et al. “Quantitative fetal fibronectin for the prediction of preterm birth in symptomatic women”. In: Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Edition 97 (Apr. 2012), A73–A73. doi: 10.1136/fetalneonatal-2012-301809.240.

15. Jana Hutter et al. “Multi-modal functional MRI to explore placental function over gestation”. In: Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 81.2 (2019), pp. 1191–1204. doi: https ://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.27447. eprint: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/mrm.27447. url: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/mrm.27447.

16. R.D. Cook and S. Weisberg. Residuals and Influence in Regression. Monographs on statistics and applied probability. Chapman and Hall, 1986. url: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=aMDpswEACAAJ.

17. Melissa Azur et al. “Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations: What is it and how does it work?” In: International journal of methods in psychiatric research 20 (Mar. 2011), pp. 40–9. doi: 10.1002/mpr.329.

18. Dimitris Bertsimas, Colin Pawlowski, and Ying Zhuo. “From predictive methods to missing data imputation: An optimization approach”. In: Journal of Machine Learning Research 18 (Apr. 2018), pp. 1–39.

19. Robert Goldenberg et al. “Epidemiology and Causes of Preterm Birth”. In: Lancet 371 (Feb. 2008), pp. 75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4.

20. G. Casella, R.L. Berger, and Brooks/Cole Publishing Company. Statistical Inference. Duxbury advanced series in statistics and decision sciences. Thomson Learning, 2002, p. 556. isbn: 9780534243128. url: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=0x%5C_vAAAAMAAJ.

21. Damjan Krstajic et al. “Cross-validation pitfalls when selecting and assessing regression and classification models”. In: Journal of cheminformatics 6 (Mar. 2014), p. 10. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-10.

22. Stephanie Purisch and Cynthia Gyamfi. “Epidemiology of preterm birth”. In: Seminars in Perinatology 41 (Sept. 2017). doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.07.009.

Figures