1374

Cardiac MR Denoising Inline Neural Network (CaDIN).

Siyeop Yoon1, Salah Assana1, Manuel A. Morales1, Julia Cirillo1, Patrick Pierce1, Beth Goddu1, Jennifer Rodriguez1, and Reza Nezafat1

1Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

1Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Image Reconstruction

The diagnostic confidence in the interpretation of cardiac MR scans can be improved by enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Traditional image denoising has been studied extensively to improve SNR in cardiac MRI, but with limited success due to the resulting blurring. In this study, we sought to develop and evaluate cardiac MR denoising inline neural network (CaDIN) for improving SNR in cardiac MRI.Introduction

The diagnostic confidence in the interpretation of cardiac MR scans can be improved by enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Traditional image denoising has been studied extensively to improve SNR in cardiac MRI with limited success due to the resulting blurring. The recent advances in deep learning (DL) techniques showed the potential to surpass the performance of traditional denoising algorithms. However, there have been limited data on the potential of DL-based denoising in cardiac MR. Additionally, the existing DL-based methods synthesized training data in the image domain that cannot reflect the g-factor and B1 correction, limiting their potential use. Finally, offline implementations have limited their clinical usage, and DICOM bit-quantization altered noise characteristics, resulting in a discrepancy between training and actual acquisition. In this study, we sought to develop and evaluate cardiac MR denoising inline neural network (CaDIN). Training data were synthesized by acquiring and modifying the coil-wise MR noise and reconstructed using the same pipeline as the inline vendor reconstruction.Method

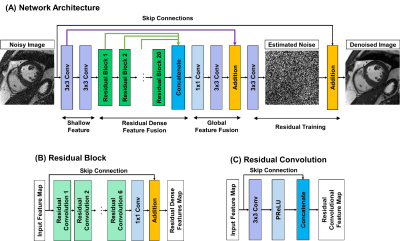

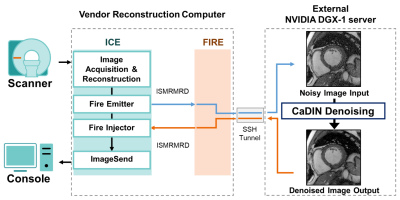

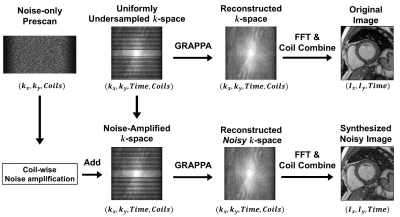

CaDIN receives a noise image and outputs an image with high fidelity with reduced noise. The CaDIN was based on the residual dense neural network1 and trained for cardiac MRI denoising task (Figure 1). CaDIN uses the hierarchical features of input images via residual connections. The feature fusion mechanism makes the network learn both local and global features more efficiently. This local/global feature extraction captures both local details and globally scattered image noise. Compared to the original residual dense neural network, CaDIN uses a residual learning framework to explicitly learn the difference between the noisy image and the nearly noise-free image. Therefore, the training of network does not rely on the assumptions, such as a noise model and spatial homogeneity. These properties benefit MRI noise reduction because the noise is globally distributed and can be spatially varied with parallel imaging techniques. The inline integration is critical to enable the usage of full bit-depth of the data, preventing noise characteristics alteration. CaDIN was seamlessly integrated with the clinical scanner using the Siemens Framework for Image Reconstruction prototype2, the inline integration is detailed in Figure 2. We retrospectively extracted noise-only prescan, and k-space data of 2D cine from 346 patients who underwent a clinical cardiac MRI; written informed consent was waived by the IRB. Imaging was performed at 3T using a Siemens Vida system with the following parameters; repetition/echo time = 3.0-3.5/1.4-1.5ms, flip angle 33-43°, in-plane spatial resolution of 1.7×1.7 mm2, slice thickness 8 mm, matrix size 132-210 × 192-208, field of view 220-380 × 306-360 mm2, and 2-fold acceleration with GRAPPA. The data were randomly divided into training (272 patients), validation (37 patients), and testing (37 patients).The training data consisted of noisy and original image pairs. We scaled the noise data at different levels, which were then added to the coil-specific MR signal (Figure 3) to simulate imaging with the different noise levels. The noise characteristic of i-th coil is represented as complex-valued Gaussian distribution, εi~N(μre,μre,σre,σim), where μre and μim are the means of real and imaginary parts, and σre and σim are the standard deviations of real and imaginary parts, respectively. The mean and standard deviation were estimated from the noise-only prescan. The noisy MR measurement of i-th coil, k'i, can be expressed as; k'i=ki+εi, where ki is a signal under ideal conditions and the noise characteristic of i-th coil is assumed as εi from coil-specific prescan. Therefore, the synthesized signal with n-fold noise-amplification is expressed as follows; k''i=k'i+n×εi.

We synthesized a training dataset corresponding to 6.25-25% of the original coil SNR (n=3 to 15). The training images were reconstructed using the same pipeline as the inline reconstruction, which includes the vendor’s parallel imaging and B1 correction. The training data were randomly cropped to 128 by 128, and the batch size was 16. The learning rate was 0.0001 and the maximum iteration was 120k using L1 loss with Adam (β1=0.9 and β2=0.999). CaDIN was implemented in Python (version 3.7; Python Software Foundation) using PyTorch and was trained on a DGX-1 workstation (NVIDIA, California).

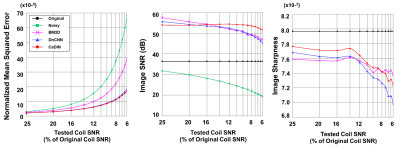

To evaluate the performance of CaDIN, we measured normalized mean squared error (NMSE), image sharpness, and region of interest-based image SNR. The image sharpness is assessed by the maximum absolute gradient at the blood-to-endocardial boundary. Image SNR is defined as; SNRi = 20×Log(μBlood/σBackground), where μBlood is the mean signal intensity of the blood pool, and σBackground is a standard deviation of background noise. Additionally, we compared the performance of CaDIN with Block-matching 3D filtering (BM3D)3 and denoising convolutional neural network (DnCNN)4. BM3D is a non-local mean-based denoising technique, training is not required. DnCNN is a DL-based denoising technique; we trained DnCNN using the same training dataset as CaDIN. The hyperparameters of DnCNN were identical to CaDIN.

Results

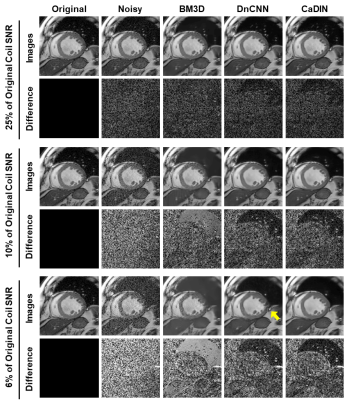

CaDIN improved image SNR while and the image sharpness was slightly decreased compared to the original image (Figure 4). The NMSE of CaDIN was lower than that of BM3D and DnCNN in all noise ranges of the test. CaDIN successfully suppressed noise in all images without significant blurring (Figure 5).Conclusion

We demonstrated the potential of cardiac MR denoising inline neural network to improve image quality without generating any additional artifacts.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Zhang Y, Tian Y, Kong Y, Zhong B, Fu Y. Residual dense network for image restoration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell., 2020; 43(7): 2480-2495.

2. Chow K, Xue H, Kellman P. Prototyping Image Reconstruction and Analysis with FIRE. Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Virtual Scientific Sessions, 2021.

3. Lebrun M. An analysis and implementation of the BM3D image denoising method. Image Processing On Line, 2012; 175-213.

4. Zhang K, Zuo W, Chen Y, Meng D, Zhang L. Beyond a gaussian denoiser: Residual learning of deep cnn for image denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process., 2017; 26(7): 3142-3155.

Figures

Figure 1. The architecture of cardiac MR denoising inline neural network (CaDIN). Architecture of the original residual dense neural network was modified to explicitly learn the noise component via residual training scheme (A). CaDIN combines the hierarchical features of the residual blocks (B) and the input image using skip-connection for the residual training. Each residual block has six residual convolution (C) for concatenating the local features. The parametric rectified linear unit activation function (PReLU) is trained to prevent the gradient vanishing.

Figure 2. The pipeline of inline integration of cardiac MR denoising inline neural network (CaDIN) via the Siemens Framework for Image Reconstruction prototype. The CaDIN denoising process was seamlessly inserted into the vendor’s reconstruction pipeline to prevent noise characteristics alternation. After image acquisition and reconstruction is completed in the scanner reconstruction computer, the noisy images are sent to the external server for the CaDIN denoising process. Then, the original and denoised images are immediately available on the console.

Figure 3. The pipeline for data synthetization using noisy-only prescan and k-space data. The coil-wise noise characteristics were estimated using the noise-only prescan data. The coil-wise noise was amplified and added to the original k-space data to emulate the noisy acquisition. The training image pairs consisting of the original and synthesized noise images were generated using the same pipeline as the inline reconstruction, which includes the vendor’s GRAPPA reconstruction algorithm and proper coil combination.

Figure 4. The performance evaluation of denoising methods tested on the images of 6.3 to 25% original coil signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Cardiac MR denoising inline neural network (CaDIN) has a smaller normalized mean squared error and improved SNR compared to Block-matching 3D filtering (BM3D) and denoising convolutional neural network (DnCNN). The image sharpness of CaDIN was higher than DnCNN but lower than the original image.

Figure 5. The comparison among the original, noisy, and denoised images using block-matching 3D filtering (BM3D), denoising convolutional neural network (DnCNN), and cardiac MR denoising inline neural network (CaDIN). The BM3D show significantly blurred results in 6% and 10% of the original coil SNR image. DnCNN generates residual artifacts (yellow arrow) in highly deteriorated input, while CaDIN shows excellent image quality.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1374