1373

A Deep Learning Method to Remove Motion Artifacts in Fetal MRI1Department of Electrical, Computer and Biomedical Engineering, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Institute for Biomedical Engineering, Science and Technology (iBEST), Toronto Metropolitan University and St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Division of Neuroradiology, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 5Department of Medical Imaging, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Artifacts, Deep Learning, Generative Adversarial Network, Image Denoising

Motion artifacts are a common issue in fetal MR imaging that limit the visibility of essential fetal anatomy. In such cases, the sequence acquisition must be repeated in order for an accurate diagnosis. This study introduces a deep learning approach utilizing a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) framework for removing motion artifacts in fetal MRIs. Results exceeded current state-of-the-art methods by achieving an average SSIM of 93.7%, and PSNR of 33.5dB. The presented network demonstrates rapid and accurate results that can be advantageous in clinical use.Introduction

Fetal MR imaging is the accepted modality for capturing fetal anatomy mainly due to its ability to acquire superb tissue contrast. However, imaging artifacts can hinder the visibility of fetal tissue and thus limit diagnostic interpretation. The most common type of artifact is caused by motion where current solutions include using different sequence types and patient dependent techniques such as maternal breath-hold1. These solutions are non-optimal for all patients and therefore a more robust motion artifact reduction strategy is needed.Methods

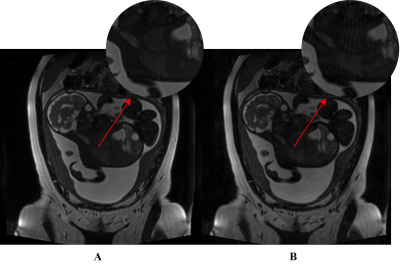

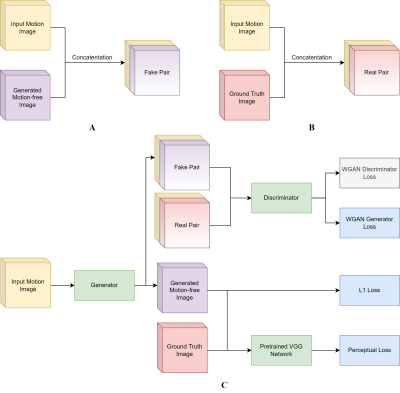

The fetal MRI dataset used in this study was acquired from The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. The resulting 2-dimensional (2D) images in each scan were assessed by 2 pediatric neuroradiologists for the presence/absence (1/0) of motion artifacts. The motion-free images were used to generate a synthetic motion-corrupted image, creating an image pair with and without motion artifacts (shown in Figure 1) and utilized for network training/validation. In total, the training set consisted of 855 paired images, and the validation and testing set each contained 285 paired images.A Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) approach was adopted where the main components are a Generator and Discriminator. The Generator’s goal is to effectively remove motion artifacts from the affected images. The generated motion-free image and the ground truth are separately concatenated with the original motion-corrupted image to form two sets of pairs as shown in Figure 2A and 2B. The input to the Discriminator are the constructed image pairs where the Discriminator aims to differentiate between the “real” and “fake” pairs. The entire workflow is illustrated in Figure 2C.

An Autoencoder architecture was implemented as the framework of the Generator. It incorporates modified Residual blocks and long skip connections. The Autoencoder first encodes the images by reducing their spatial dimensions through a series of convolution layers. This is followed by 9 Residual blocks with SE that have shown to avoid vanishing gradients and provide emphasis on significant features, respectively2,3. Lastly, the image is decoded where the features are upsampled to the original dimensions by a series of transpose convolution layers. The final outputs are motion-free versions of the original input images.

The architecture of the Discriminator follows a standard sequential CNN approach. The output of the discriminator corresponds to whether the input image pair was “real” or “fake”.

The Discriminator loss is based on the WGAN loss introduced by Gulrajani et. al4 which improves on the original GAN loss by computing Wasserstein distance as opposed to cross-entropy. The Generator loss is composed of a WGAN, mean absolute error (L1), and perceptual loss that utilizes the feature outputs from a pretrained VGG-19 network.

The experiments consisted of deploying the Generator and measuring Structural similarity index measure (SSIM), and peak signal to noise ratio (PSNR). Our proposed network was also compared with other common motion correction methods such as BM3D4, RED-Net5, non-local means (NLM) filtering6, and WGAN-VGG7. A further ablation study was also performed to ensure network components were operating to standard.

Results

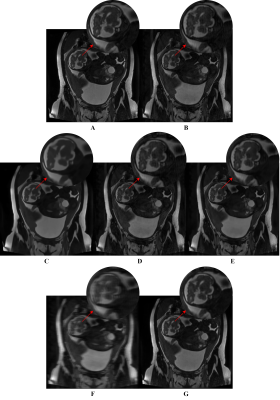

The network results are summarized in Table 1. Example outputs are shown in Figure 3. Table 2 displays the results obtained from the ablation study.Discussion

The proposed network was able to achieve an average SSIM of 93.68% and PSNR of 33.54dB. These results exceeded other state-of-the-art methods such as BM3D, RED-Net, NLM filtering, and WGAN-VGG. In a qualitative assessment, the proposed network produced desirable results in comparison to the other methods which suffered from a combination of oversmoothing, incomplete artifact removal, and blurring. These results are in agreement with other works that compared similar approaches in denoising tasks8-11.The ablation study confirmed that all components of the network provided improved performance. Notably, the L1 loss had the most impact where network performance decreased significantly when it was removed. In addition, SE had a minor effect but still remained in the network due to their low computational cost.

Conclusion

A novel fetal MRI motion artifact correction strategy was introduced in this work. Following a GAN framework, the proposed network achieved results that surpassed existing motion correction methods. It was able to consistently diminish motion artifacts, highlighting its potential for use in clinical practice to reduce the number of repeated sequence acquisitions due to motion artifacts limiting the visibility of fetal anatomy. Future work includes having radiologists assess the network's reliability and workflow impact in a clinical setting.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgements.References

1. M. Zaitsev, Julian. Maclaren, and M. Herbst, “Motion Artefacts in MRI: a Complex Problem with Many Partial Solutions,” J Magn Reson Imaging, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 887–901, Oct. 2015, doi: 10.1002/jmri.24850.

2. R. Yasrab, “SRNET: A Shallow Skip Connection Based Convolutional Neural Network Design for Resolving Singularities,” J. Comput. Sci. Technol., vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 924–938, Jul. 2019, doi: 10.1007/s11390-019-1950-8.

3. A. G. Roy, N. Navab, and C. Wachinger, “Recalibrating Fully Convolutional Networks With Spatial and Channel ‘Squeeze and Excitation’ Blocks,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 540–549, Feb. 2019, doi: 10.1109/TMI.2018.2867261.

4. K. Dabov, A. Foi, V. Katkovnik, and K. Egiazarian, “Image Denoising by Sparse 3-D Transform-Domain Collaborative Filtering,” IEEE transactions on image processing : a publication of the IEEE Signal Processing Society, vol. 16, pp. 2080–95, Sep. 2007, doi: 10.1109/TIP.2007.901238.

5. X.-J. Mao, C. Shen, and Y.-B. Yang, “Image Restoration Using Very Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Networks with Symmetric Skip Connections,” arXiv:1603.09056 [cs], Aug. 2016, Accessed: Dec. 28, 2021. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1603.09056.

6. A. Buades, B. Coll, and J.-M. Morel, “A Non-Local Algorithm for Image Denoising,” in 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05), San Diego, CA, USA, 2005, vol. 2, pp. 60–65. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2005.38.

7. Q. Yang et al., “Low Dose CT Image Denoising Using a Generative Adversarial Network with Wasserstein Distance and Perceptual Loss,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 1348–1357, Jun. 2018, doi: 10.1109/TMI.2018.2827462.

8. X.-J. Mao, C. Shen, and Y.-B. Yang, “Image Restoration Using Very Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Networks with Symmetric Skip Connections,” arXiv:1603.09056 [cs], Aug. 2016, Accessed: Dec. 28, 2021. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1603.09056.

9. Z. Li et al., “Low-Dose CT Image Denoising with Improving WGAN and Hybrid Loss Function,” Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, vol. 2021, p. e2973108, Aug. 2021, doi:

10.1155/2021/2973108.10. M. Tian and K. Song, “Boosting Magnetic Resonance Image Denoising With Generative Adversarial Networks,” IEEE Access, vol. PP, pp. 1–1, Apr. 2021, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3073944.

11. N. T. Trung, D.-H. Trinh, N. L. Trung, and M. Luong, “Low-dose CT image denoising using deep convolutional neural networks with extended receptive fields,” SIViP, vol. 16, no. 7, pp. 1963–1971, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s11760-022-02157-8.

Figures