1372

Can we predict motion artifacts in clinical MRI before the scan completes?1Department of Radiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 2Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 3Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States, 4Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Artifacts, deep learning, AI-guided radiology, neuroimaging, computer vision

Subject motion remains the major source of artifacts in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Motion correction approaches have been successfully applied in research, but clinical MRI typically involves repeating corrupted acquisitions. To alleviate this inefficiency, we propose a deep-learning strategy for training networks that predict a quality rating from the first few shots of accelerated multi-shot multi-slice acquisitions, scans frequently used for neuroradiological screening. We demonstrate accurate prediction of the scan outcome from partial acquisitions, assuming no further motion. This technology has the potential to inform the operator's decision on aborting corrupted scans early instead of waiting until the acquisition completes.Introduction

Clinical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) makes routine use of multi-slice sequences with two-dimensional (2D) encoding that acquire each k-space slice over several shots, such as fast spin echo (FSE)1. Unfortunately, these scans are vulnerable to motion between shots, making patient motion a predominant source of artifacts.While techniques such as PROPELLER2 successfully correct for in-plane motion after the fact, retrospective correction of through-plane motion is challenging3. Prospective correction dynamically updates the acquisition as motion happens in the scanner but has not been adopted clinically. Instead, MRI technologists typically repeat the FSE sequence if the image exhibits artifacts.

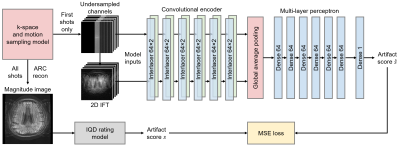

We present a deep-learning strategy alleviating the inefficiency of waiting until the end of data acquisition before image quality can be assessed (Figure 1). While previous techniques require a reconstructed magnitude image to predict an artifact level4-6, our networks take as input only the first few k-space segments, to provide the user with an estimate of the likely outcome of the MRI scan.

Method

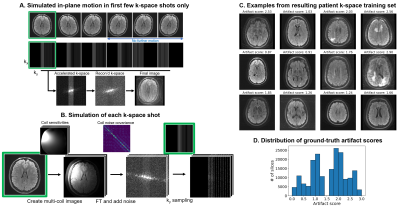

We train a deep neural network $$$h$$$ to predict image quality $$$s$$$ from the first $$$N$$$ k-space shots of a multi-shot 2D MRI acquisition only, assuming no further motion occurs in the remaining shots (Figure 2). We generate suitable training data by simulating motion between the first $$$N$$$ shots only, and based on the image reconstructed from all shots, we assign a ground-truth artifact rating to the $$$N$$$-shot network input.Training data generation

Let $$$k=SFCx$$$ be the multi-shot multi-channel k-space of motion-free magnitude image $$$x$$$, where $$$C$$$ denotes the coil sensitivity, $$$F$$$ denotes the Fourier Transform, and $$$S$$$ denotes the $$$k_y$$$ sampling. To generate motion-corrupted $$$\tilde{k}$$$, we separately move $$$x$$$ for each shot $$$i$$$ and multiply by ESPIRiT7 coil-sensitivity profiles, producing multi-channel images $$$\{Cx_i\}$$$. We form $$$\tilde{k}$$$ by combining the $$$k_y$$$ lines of each $$$k_i=S_iFCx_i$$$ corresponding to shot $$$i$$$ after adding correlated Gaussian noise to the real and imaginary components based on noise covariance measurements (Figure 2).

Ground-truth scores

For training, we obtain ground-truth artifact scores from magnitude images reconstructed from $$$\tilde{k}$$$ by using the Image Quality Dashboard model6 (IQD), an internal rating tool, which achieves good artifact classification. Trained by the original authors on radiologist ratings, IQD predicts a score $$$s\in[0, 3]$$$, where $$$s=0$$$ means no artifact.

Artifact-rating model

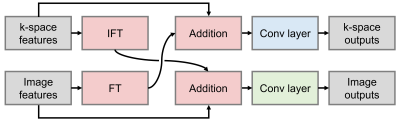

Network $$$h_\theta$$$ with parameters $$$\theta$$$ predicts the scalar artifact score $$$\hat{s}=h_\theta(k)$$$ from zero-filled complex multi-channel k-space $$$k$$$. A series of Interlacer-type8 layers (Figure 3) extract image and k-space features, which we condense using global average pooling before regression (Figure 1). We choose these layers because they have been shown to perform better than convolutions in image or k-space alone8. We implement $$$h_\theta$$$ in TensorFlow9 and fit $$$\theta$$$ by optimizing a mean-squared-error (MSE) loss on $$$\hat{s}$$$ until convergence (batch size 2, learning rate $$$10^{-4}$$$).

Experiment

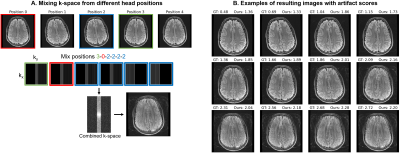

DataFor training, we generate a total of 180k axial T2-FLAIR FSE slices with different motion using k-space collected from 349 MGH outpatient scans, holding out 3 subjects for validation (ARC $$$R=3$$$, 23 interleaved 4.5-mm slices with 6 k-space segments, TR/TI/TE 10000/2600/118 ms, FA 90$$$^\circ$$$). For testing, we scan a volunteer with the same sequence in five different head positions and form corrupted datasets by substituting the first 3 segments across acquisitions (Figure 5A). We use a 3-T General Electric Signa Premier system with a 48-channel head coil, discarding 4 neck channels.

Setup

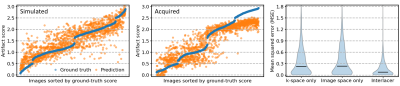

We train partial k-space models using only the first $$$N=3$$$ of 6 shots as input, corresponding to an artifact rating after 50% of the acquisition. We assess performance in terms of mean squared error, on simulated-motion data from held-out subjects, and acquired volunteer scans. To assess the benefit of applying convolutions in both image and k-space using Interlacer-type layers, we train baseline models with matched capacity, applying convolutions in either space only.

Results

Figure 4 compares in-distribution and out-of-distribution artifact-rating accuracy. Although the model only has access to 50% of k-space, it generalizes to out-of-distribution data, with some outliers for scores $$$s>2.5$$$. The Interlacer-type model outperforms the baselines that operate in image or k-space only. Figure 5B shows representative example images across a range of artifact scores.

Discussion

We present a simulation-based strategy for training networks to predict the outcome of multi-shot MRI before the scan completes and demonstrate its suitability for acquired data.Ground-truth scores

Our training strategy can be applied to anatomies other than the brain, given ground-truth ratings. Rather than labeling training data manually, we leverage IQD from prior work6 to reduce the human effort but plan to replace this dependency with a metric quantifying the injected motion and $$$k_y$$$ pattern.

Phase-encode pattern

While we train models with a standard FSE $$$k_y$$$ scheme to support routine clinical exams, an optimized scheme may enable earlier prediction of image quality. Trained with the appropriate MRI contrast and $$$k_y$$$ pattern, the model could support any multi-shot sequence.

Conclusion

We demonstrate the feasibility of predicting motion artifacts when the scan is only half complete. The technology has the potential to improve efficiency in the radiology unit by informing the operator's decision on aborting the acquisition early.Acknowledgements

The authors thank Bernardo Bizzo and Dufan Wu for model sharing, and Kathryn Evancic, Marcio Rockenbach, Eugene Milshteyn, Dan Rettmann, Sabrina Qi, Suchandrima Banerjee, Arnaud Guidon, and Anja Brau for assistance and helpful discussions.

The project benefited from funding from General Electric Healthcare. Additional support for this research was provided in part by the BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network (U01 MH117023), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (P41 EB015896, P41 EB015902, P41 EB030006, R01 EB023281, R01EB032708, R01 EB019956, R21 EB029641, R21 EB018907), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K99 HD101553), the National Institute on Aging (R56 AG064027, R01 AG016495, R01 AG070988), the National Institute of Mental Health (RF1 MH121885, RF1 MH123195), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS070963, R01 NS083534, R01 NS105820). Additional support was provided by the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research (U01 MH093765), part of the multi-institutional Human Connectome Project. The project was made possible by the resources provided by Shared Instrumentation Grants (S10 RR023401, S10 RR019307, S10 RR023043) and by computational hardware generously provided by the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center (https://www.masslifesciences.com).

Bruce Fischl has a financial interest in CorticoMetrics, a company whose medical pursuits focus on brain imaging and measurement technologies. This interest is reviewed and managed by Massachusetts General Hospital and Mass General Brigham in accordance with their conflict of interest policies.

References

1. Hennig J et al. RARE imaging: a fast imaging method for clinical MR. Magn Reson Med. 1986;3(6):823-833.

2. Pipe JG. Motion correction with PROPELLER MRI: application to head motion and free-breathing cardiac imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42(5):963-9.

3. Norbeck O et al. T1-FLAIR imaging during continuous head motion: Combining PROPELLER with an intelligent marker. Magn Reson Med. 2021;85(2):868-82.

4. Sujit SJ et al. Automated image quality evaluation of structural brain MRI using an ensemble of deep learning networks. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;50(4):1260-7.

5. Sreekumari A et al. A Deep Learning–Based Approach to Reduce Rescan and Recall Rates in Clinical MRI Examinations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2019;40(2):217-23.

6. Bizzo BC et al. Machine Learning Model For Motion Detection And Quantification On Brain MR: A Multicenter Testing Study. RSNA, Chicago, IL. 2021.

7. Uecker M et al. ESPIRiT - An Eigenvalue Approach to Autocalibrating Parallel MRI: Where SENSE meets GRAPPA. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(3):990-1001.

8. Singh NM et al. Joint Frequency and Image Space Learning for MRI Reconstruction and Analysis. Machine Learning for Biomedical Imaging. 2022;1:1-28.

9. Abadi M et al. TensorFlow: a system for Large-Scale machine learning. USENIX, Savannah, GA. 2016:265-83.

Figures