1371

Motion-Aware Neural Networks Improve Rigid Motion Correction of Accelerated Segmented Multislice MRI1Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), MIT, Cambridge, MA, United States, 2Harvard-MIT Health Sciences and Technology, MIT, Cambridge, MA, United States, 3Department of Radiology, Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, MA, United States, 4Department of Radiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 5Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, MIT, Cambridge, MA, United States, 6Institute for Medical Engineering and Science, MIT, Cambridge, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Motion Correction, Image Reconstruction, Deep Learning

We demonstrate a deep learning approach for fast retrospective intraslice rigid motion correction in segmented multislice MRI. A hypernetwork uses auxiliary rigid motion parameter estimates to produce a reconstruction network based on the motion parameters that are specific to the input image. This strategy produces higher quality reconstructions than those produced by model-based techniques or by networks that do not use motion estimates. Further, this approach mitigates sensitivity to misestimation of the motion parameters.Author Information

* Denotes equal contribution.Background

Motion frequently corrupts MRI acquisitions, degrading image quality or necessitating repeated scans1. Recent advances promise real-time motion estimates, including external tracking2, navigators3, and SAMER4. We demonstrate a deep learning technique for retrospective intraslice rigid motion correction in 2D fast spin echo (FSE) brain MRI that uses motion estimates to mitigate image artifacts. We employ a hypernetwork5 -- a network that outputs weights of another network -- to convert estimated motion parameters into a motion state-specific reconstruction network.We assume a quasistatic motion model where the object only moves via 2D rotations and translations between shots. We defer modeling through-slice motion for future work.

Methods

DataWe demonstrate our approach on 2D T2 FLAIR FSE brain MRI k-space signals (3T GE Signa Premier, 48-channel head coil, 6-shot acquisition, TR=10s, TE=118ms, TI=2.6s, FOV=260x260mm2, acquisition matrix=416x300, slice thickness=5mm, slice spacing=1mm) acquired at Massachusetts General Hospital under an approved IRB protocol. We split the dataset into 553/197/153 training/validation/test 2D slices from 31/11/9 subjects respectively, with no subject overlap between sets. We treat the acquired data as ground truth and simulate motion artifacts during training and testing.

Network Architectures and Training

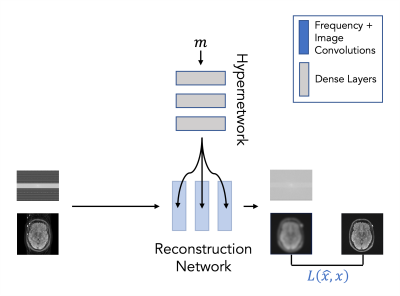

Our strategy ('ARC-HN') includes two components (Figure 1): (i) a hypernetwork that uses fully-connected layers to generate weights of a reconstruction subnetwork from motion parameter estimates and (ii) the reconstruction subnetwork that performs motion-corrected reconstruction. This architecture enables the reconstruction strategy to vary with the motion parameters and match the corruption process better. The motion parameters comprise 18 scalars representing x- and y- translations and a rotation for each of 6 shots. The input to the reconstruction subnetwork is 88-channel real and imaginary components of the ARC parallel imaging reconstruction6 (Orchestra SDK - GE Healthcare) of k-space data from 44 receive coils (4 neck channels were discarded). The final reconstruction subnetwork output is 88-channel k-space data converted to the reconstructed image via the inverse Fourier transform and root-sum-of-squares coil combination.

We compare our strategy to four methods:

- ARC, which applies parallel imaging reconstruction without motion correction

- Model-Based reconstruction that applies phase shifts and rotations to the ARC reconstruction to undo motion7 and then applies the non-uniform fast Fourier transform8,9

- ARC-Baseline, a deep learning method that takes the ARC reconstruction as input and does not incorporate motion parameters (the same network is applied to all inputs regardless of motion state)

- RAW-HN, a hypernetwork whose reconstruction subnetwork takes raw k-space data as input instead of the ARC reconstruction.

Motion Simulation

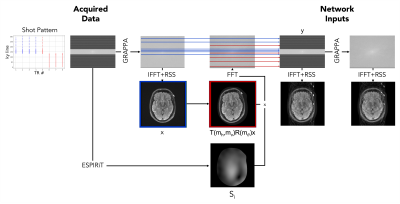

Figure 2 illustrates our motion simulation process. We first apply ARC reconstruction to motion-free k-space data, followed by the inverse Fourier transform and root-sum-of-squares coil combination to form the motion-free image $$$x$$$. We estimate coil sensitivity profiles $$$S_i$$$ using ESPIRiT11 with learned parameter selection12 and extend these profiles to the edge of the image domain via B-spline interpolation. We synthesize motion-corrupted measurements for coil $$$i$$$ as $$y_i=A_i(m)x+\epsilon,$$ where $$A_i=P_{pre}FS_i+P_{post}FS_iT(m_h,m_v)R(m_\theta)$$ is the forward model that incorporates sampled rotations ($$$R$$$) and translations ($$$T$$$) as well as the Fourier transform ($$$F$$$), and $$$\epsilon$$$ is noise drawn from a Rician distribution. We define the motion matrices $$$R$$$ and $$$T$$$ by selecting a random shot affected by motion and sampling horizontal and vertical translation parameters $$$m_h$$$, $$$m_v$$$ and rotation parameter $$$m_\theta$$$ from uniform distributions over the ranges [-10mm,+10mm] and [-45o,45o], respectively. The undersampling operator $$$P$$$ mixes k-space lines before ($$$P_{pre}$$$) and after ($$$P_{post}$$$) motion such that $$$y_i$$$ would have been acquired had the subject shifted between two positions during the acquisition.

We also simulate a realistic test example by mixing acquired k-space measurements $$$y_{i,1}$$$ and $$$y_{i,2}$$$ from two scans of the same subject in different positions: $$$y_i=P_{pre}y_{i,1}+P_{post}y_{i,2}$$$.

Implementation Details

We normalize each input/output pair by dividing by the maximum intensity in the corrupted image. Every network is trained to reconstruct a normalized version of the image ($$$x$$$ or $$$T(m_h,m_v)R(m_\theta)x$$$) corresponding to the central k-space line. All models are trained with the structural similarity index measure (SSIM) loss function using the Adam optimizer (learning rate 1e-3) and batch size 6. We tune hyperparameters on the validation set and use the test set for final evaluation. All networks take 7 days to train and 200 milliseconds for inference on an NVIDIA RTX 8000 GPU.

Results

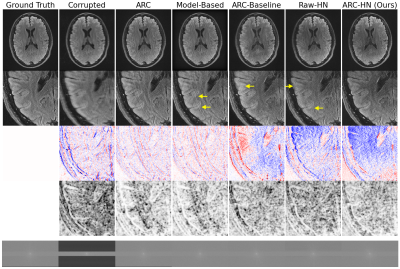

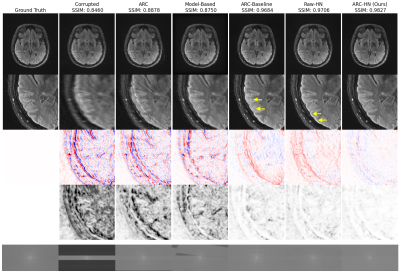

The proposed hypernetwork produces sharper, more accurate reconstructions than ARC and Model-Based reconstructions (Figure 3). Our method also quantitatively outperforms classical and deep learning baselines and is less sensitive to motion parameter misestimation than Model-Based reconstruction (Figure 4). Though our method is trained on simulated data, it generalizes to realistic motion-corrupted k-space signals (Figure 5). In all tests, ARC-HN shows the best performance.Conclusions

We demonstrate a deep learning approach for correcting rigid motion artifacts in 2D FSE T2 FLAIR MRI. Our approach incorporates motion parameter estimates and improves on classical strategies, while offering robustness to misestimated motion parameters. Using ARC reconstruction instead of undersampled k-space data as input improves network performance by allowing it to focus solely on the motion artifact correction task.Acknowledgements

Research reported in this abstract was supported in part by GE Healthcare and by computational hardware provided by the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center. We also thank Steve Cauley and Neel Dey for helpful discussions.

Additional support was provided by NIH NIBIB (5T32EB1680, P41EB015896, 1R01EB023281, R01EB006758, R21EB018907, R01EB019956, R01EB017337, P41EB03000, R21EB029641, 1R01EB032708), NIBIB NAC (P41EB015902), NICHD (U01HD087211, K99 HD101553), NIA (1R56AG064027, 1R01AG064027, 5R01AG008122, R01AG016495, 1R01AG070988, RF1AG068261), NIMH (R01 MH123195, R01 MH121885, 1RF1MH123195), NINDS (R01NS0525851, R21NS072652, R01NS070963, R01NS083534, 5U01NS086625, 5U24NS10059103, R01NS105820), and the Blueprint for Neuroscience Research (5U01-MH093765), part of the multi-institutional Human Connectome Project. Additional support was provided by the BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network grant U01MH117023, and a Google PhD Fellowship.

References

- Andre, Jalal B., et al. "Toward quantifying the prevalence, severity, and cost associated with patient motion during clinical MR examinations." Journal of the American College of Radiology 12.7 (2015): 689-695.

- Frost, Robert, et al. "Markerless high‐frequency prospective motion correction for neuroanatomical MRI." Magnetic resonance in medicine 82.1 (2019): 126-144.

- Tisdall, M. Dylan, et al. "Volumetric navigators for prospective motion correction and selective reacquisition in neuroanatomical MRI." Magnetic resonance in medicine 68.2 (2012): 389-399.

- Polak, Daniel, et al. "Scout accelerated motion estimation and reduction (SAMER)." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 87.1 (2022): 163-178.

- Ha, David, Andrew Dai, and Quoc V. Le. "Hypernetworks." arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.09106 (2016).

- Brau, Anja CS, et al. "Comparison of reconstruction accuracy and efficiency among autocalibrating data‐driven parallel imaging methods." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 59.2 (2008): 382-395.

- Gallichan, Daniel, José P. Marques, and Rolf Gruetter. "Retrospective correction of involuntary microscopic head movement using highly accelerated fat image navigators (3D FatNavs) at 7T." Magnetic resonance in medicine 75.3 (2016): 1030-1039.

- Fessler, Jeffrey A., and Bradley P. Sutton. "Nonuniform fast Fourier transforms using min-max interpolation." IEEE transactions on signal processing 51.2 (2003): 560-574.

- Muckley, Matthew J., et al. "TorchKbNufft: a high-level, hardware-agnostic non-uniform fast Fourier transform." ISMRM Workshop on Data Sampling & Image Reconstruction. 2020.

- Singh, Nalini M. et al. “Joint Frequency and Image Space Learning for MRI Reconstruction and Analysis”. Journal of Machine Learning for Biomedical Imaging, 2022:018: pp 1-28.

- Uecker, Martin, et al. "ESPIRiT—an eigenvalue approach to autocalibrating parallel MRI: where SENSE meets GRAPPA." Magnetic resonance in medicine 71.3 (2014): 990-1001.

- Iyer, Siddharth, et al. "SURE‐based automatic parameter selection for ESPIRiT calibration." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 84.6 (2020): 3423-3437.

Figures

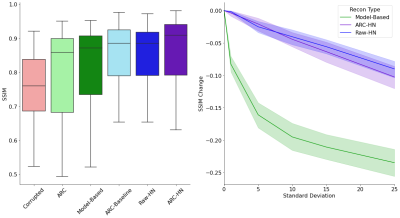

Fig 4. Reconstruction Accuracy Statistics.

Left: SSIM scores for all methods. ARC-HN (purple) outperforms classical (green) and deep learning (blue) baselines.

Right: Sensitivity to misestimated motion parameters. Noise of increasing standard deviation is added to true motion parameters provided to the reconstruction method. SSIM reduction due to motion misestimation is reported for motion-aware methods. Hypernetworks are less sensitive to noisy parameters than model-based reconstruction.