1368

Attention-guided network for image registration of accelerated cardiac CINE1Medical Image And Data Analysis (MIDAS.lab), Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, University Hospital of Tuebingen, Tuebingen, Germany, 2Lab for AI in Medicine, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, 3Department of Computing, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom, 4Department of Radiology, University Hospital of Tuebingen, Tuebingen, Germany, 5Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems, Tuebingen, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Motion Correction, Image registration, Image Reconstruction

Motion-resolved reconstruction methods permit for considerable acceleration for cardiac CINE acquisition. Solving for the non-rigid cardiac motion is computationally demanding, and even more challenging in highly accelerated acquisitions, due to the undersampling artifacts in image domain. Here, we introduce a novel deep learning-based image registration network, GMA-RAFT, for estimating cardiac motion from accelerated imaging. A transformer-based module enhances the iterative recurrent refinement of the estimated motion by introducing structural self-similarities into the decoded features. Experiments on Cartesian and radial trajectories demonstrate superior results compared to other deep learning and state-of-the-art baselines in terms of motion estimation and motion-compensated reconstruction.Introduction

Cardiac CINE MR permits for accurate and reproducible measurement of cardiac function. Conventionally, multi-slice 2D CINE images are acquired under multiple breath-holds leading to patient discomfort and imprecise assessment. Parallel imaging1,2 and compressed sensing3–7 have enabled the reduction of scan time, but possible acceleration is limited by achievable image quality.Incorporating motion estimation in compressed-sensing improved image quality8,9. Therefore, model-based image registration10,11 has been proposed to estimate motion from motion-resolved images. However, conventional registrations are slow and computationally demanding. They solve a pairwise optimization task that requires parametrization for each subject. Learning-based models12–14 have been alternatively proposed, as they can learn generalizable and rapid registrations. Nevertheless, these models have not yet been challenged with undersampling artifact-affected imaging data from highly accelerated acquisitions of Cartesian and non-Cartesian imaging.

In this study, we propose a deep learning model for image registration, named GMA-RAFT, that predicts non-rigid motion accurately from undersampled cardiac CINE. We adopt self-supervised learning to train the model on Cartesian and radial data. We introduce a ResNet denoiser to reduce the aliasing artifacts, that can impair motion estimation. Furthermore, we extract globally aggregated motion features to incorporate information about similar anatomical structures, that are likely to have homogeneous motion. GMA-RAFT outperforms other conventional and deep learning-based registration methods significantly in the downstream task of motion-compensated reconstruction over different accelerations and sampling trajectories.

Methods

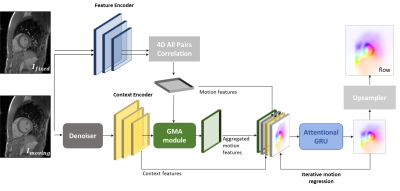

Architecture: The network architecture (Fig.1) is based on RAFT15. The dot product between all pairs of feature maps extracted from the input images is encoded into motion features. The moving image and its two adjacent frames are fed to a ResNet to reduce aliasing artifacts and then used to extract the context features. Motion features are aggregated using self-attention16 within the Global Motion Aggregation (GMA) module17. The context features $$$x$$$ represent self-similarities between pixels in the image, that will be instilled in the motion features $$$y$$$ to get the aggregated motion features $$$\hat{y}$$$, given as:$$\hat{y}=y+\alpha\sum_{n=1}^N \operatorname{softmax}(\frac {(W_\text{query}x)^T, W_\text{key}x }{\sqrt{D}})W_\text{val}y$$

where $$$\alpha$$$ is a learned parameter. $$$W_\text{query}$$$, $$$W_\text{key}$$$ and $$$W_\text{val}$$$ are projection heads for the queries and keys from the context features and for the values from the motion features. $$$D$$$ is the channels number of the context features. An iterative residual refinement decodes the extracted features to deduce the motion field using a gated recurrent unit (GRU).

The loss function includes the photometric loss ($$$\mathcal{L}_{photo}$$$) and a spatial smoothness loss ($$$\mathcal{L}_{smooth}$$$) for realistic estimates18. The mean absolute error between the ResNet output and the matching fully-sampled images ($$$\mathcal{L}_{denoiser}$$$) complements the loss:

$$\mathcal{L}=\mathcal{L}_{photo}+\beta \mathcal{L}_{smooth}+\gamma \mathcal{L}_{denoiser}$$

We optimize the loss with a batch size of 8 and AdamW (learning rate of 1e-4 and weight decay of 1e-5). The hyper-parameters $$$\beta$$$ and $$$\gamma$$$ are determined empirically ($$$\beta$$$=0.2 and $$$\gamma$$$=0.5).

The used dataset contains short-axis 2D CINE CMR acquired in-house on a 1.5T MRI in 106 subjects, with 2D bSSFP (TE/TR=1.06/2.12ms, resolution=1.9x1.9mm2, slice thickness=8mm,Nt=25 temporal phases, 8 breath-holds of 15s duration). We use 86 training and 20 test subjects. Left and right ventricular segmentation masks of 5 test subjects are manually determined by a cardiologist. The data is retrospectively undersampled using either a variable density incoherent spatiotemporal acquisition (VISTA)19 or a golden angle radial sampling20. Acceleration factors are picked uniformly from R=1 (fully-sampled) to R=16 during training.

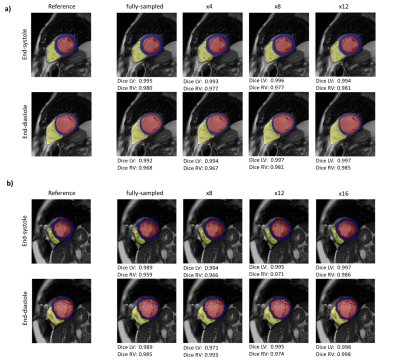

For evaluation, qualitative motion-compensated image quality is compared against a cubic B-Spline (Elastix)10, optical flow (LAP)21, VoxelMorph12 and XMorpher13 by integrating the estimated motion fields into a deformation matrix22. Segmentation masks are deformed using the estimated motion to investigate if the anatomical structures overlap well with the manually annotated masks at other time frames.

Results and Discussion

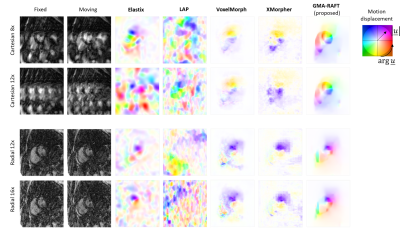

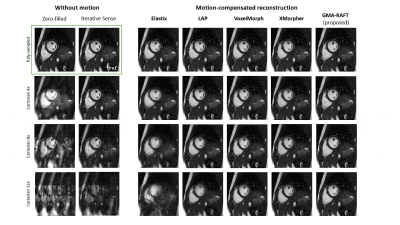

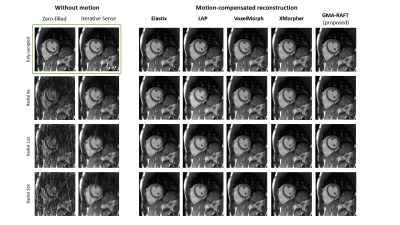

Representative motion estimates for high accelerations (Fig.2) using Cartesian and radial trajectories demonstrate that GMA-RAFT outperforms other methods in producing more consistent and precise deformation fields. The motion-compensated images for all temporal frames are shown in Fig.3 for a healthy subject using VISTA and in Fig.4 for a patient using radial sampling. Performance of motion registration for a motion-compensated reconstruction of fully-sampled and undersampled acquisitions with different accelerations is depicted. Additionally, iterative SENSE reconstructions with no motion compensation are shown. Comparative methods cannot resolve the motion for higher accelerations, i.e. motion-frozen reconstructions or suffer from residual aliasing. GMA-RAFT demonstrates more accurate reconstructions over all test settings. Results of left and right ventricular segmentation for Cartesian and radial sampling (Fig.5) is shown. They reveal consistently high fidelity to the reference over different accelerations, which is supported by the Dice between the predicted and manually annotated segmentations.We acknowledge some limitations of this work. The proposed model lacks spatial-temporal coherence as we focus on 2D pairwise registration. In the future, we want to investigate groupwise registrations to enforce spatial-temporal consistency for more precise motion tracking that can reach higher accelerations.

Conclusion

In this work, we propose a learning-based model to estimate non-rigid motion in cardiac CINE from highly undersampled data with Cartesian and radial trajectories. We demonstrated superior performance in image quality and motion field accuracy for motion-compensated reconstruction in highly accelerated cases compared to other conventional and deep learning baselines. The proposed GMA module learns similar anatomical correspondences which helps in recovering moving structures more precisely despite the presence of undersampling artifacts.Acknowledgements

S.G. and T.K. contributed equally.References

1. Kellman et al. “Fully automatic, retrospective enhancement of real-time acquired cardiac cine mr images using image-based navigators and respiratory motion-corrected averaging,” Magn Reson Med 2008;59(4).

2. Kellman et al. “High spatial and temporal resolution cardiac cine mri from retrospective reconstruction of data acquired in real time using motion correction and resorting,” Magn Reson Med 2009;62(6).

3. Osher et al. “An iterative regularization method for total variation-based image restoration,” Multiscale Modeling and Simulation 2005;4.

4. Chaâri et al. “A wavelet-based regularized reconstruction algorithm for sense parallel mri with applications to neuroimaging,” Med Image Anal 2011;15(2).

5. Block et al. “Undersampled radial mri with multiple coils. iterative image reconstruction using a total variation constraint,” Magn Reson Med 2007;57(6).

6. Liu et al. “Adaptive dictionary learning in sparse gradient domain for image recovery,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2013;22(12).

7. Weller. “Reconstruction with dictionary learning for accelerated parallel magnetic resonance imaging,” IEEE Southwest Symposium on Image Analysis and Interpretation (SSIAI) 2016.

8. Usman et al. “Motion corrected compressed sensing for free-breathing dynamic cardiac mri,” Magn Reson Med 2013;70(2).

9. Cruz et al. “One heartbeat cardiac cine imaging via jointly regularized non-rigid motion corrected reconstruction,” Proc International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) 2021.

10. Klein et al. “Elastix: a toolbox for intensity-based medical image registration,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2009;29(1).

11. Vercauteren et al. “Diffeomorphic demons: Efficient non-parametric image registration,” NeuroImage 2009;45(1).

12. Balakrishnan et al. “Voxelmorph: a learning framework for deformable medical image registration,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2019;38(8).

13. Shi et al. “Xmorpher: Full transformer for deformable medical image registration via cross attention,” International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, 2022.

14. Pan et al. “Efficient image registration network for non-rigid cardiac motion estimation,” in International Workshop on Machine Learning for Medical Image Reconstruction, 2021.

15. Teed et al. Raft: Recurrent all-pairs field transforms for optical flow,” in European conference on computer vision, Springer, 2020.

16. Vaswani et al. “Attention is all you need,” Advances in neural information processing systems 2017; 30.

17. Jiang et al. “Learning to estimate hidden motions with global motion aggregation,” in Proc IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021.

18. Brox et al. “High accuracy optical flow estimation based on a theory for warping,” in European conference on computer vision 2004.

19. Ahmad et al. “ Variable density incoherent spatiotemporal acquisition (vista) for highly accelerated cardiac mri,” Magn Reson Med 2015;74(5)

20. Winkelmann et al. “An optimal radial profile order based on the golden ratio for time-resolved mri,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2006;26(1)

21. Gilliam et al. “Local all-pass filters for optical flow estimation,” IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2015.

22. Batchelor et al. “Matrix description of general motion correction applied to multishot images,” Magn Reson Med 2005;54(5).

Figures