1359

In-vivo parcellation of human subcortex by diffusion and anatomical MRI1School of Biomedical Engineering, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2Brain and Mind Centre, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 3School of Psychology, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 4Neuroscience Research Australia, Sydney, Australia, 5Translational Research Collective, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 6Sydney Imaging, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

Synopsis

Keywords: Multi-Contrast, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, Brain, Gray matter, Segmentation, Neuro

We integrated the information from structural and diffusion MRI from a group of healthy subjects, to develop a data-driven parcellation of the human subcortex. We first identified the data features that are sensitive to the micro-architectural variabilities within subcortex and then segregated specialised sub-regions with discernible properties. Our parcellated sub-regions demonstrated remarkable similarities to known nuclei and sub-structures within striatum, globus pallidus, and thalamus. Our parcellation has also identified regions which are known to have distinct anatomical and functional properties but that are yet to be explicitly added to extant human brain atlases.INTRODUCTION

Human subcortex comprises multiple deep grey matter (DGM) structures, many with several nuclei and specialised sub-regions dedicated to highly specific functions. Detailed knowledge on the anatomy and topography of these regions are fundamental to understanding the integrative connectivity patterns within DGM structures, and the specialised cortico-DGM circuits. Histology-driven brain atlases1–2 provide the most detailed delineation of these sub-regions to date. However, the parcellation obtained from such subject-specific ex-vivo data cannot be directly applied to in-vivo MRI studies. Recent studies have attempted identification of the thalamic nuclei3 by manual delineation of histological scans combined with ex-vivo structural MRI. Functional MRI has also been employed to demonstrate the topographic organisation of human subcortex4, highlighting the potentials for MRI to probe the properties specific to the DGM subregions. However, there remains considerable discordance among the subregions defined by individual studies. Here, we focus solely on in-vivo MRI, with structural and diffusion MRI (dMRI) in particular, to integrate the information from anatomy, diffusion micro-environment, and the directionality of white matter (WM) fibres within DGM, to segregate the nuclei and specialised sub-regions in human subcortex. This work presents our MRI data-driven parcellation method, and the resulting parcels for striatum, globus pallidus, and thalamus as examples.METHODS

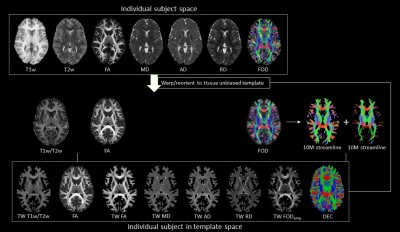

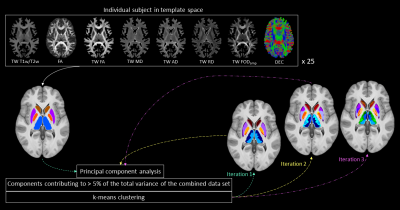

This study included minimally pre-processed T1w, T2w, and multi-shell dMRI data for 25 healthy subjects, acquired at 3T as part of the Human Connectome Project5–7. DGM regions were segmented using FSL8,9 at 1mm isotropic resolution. For each subject, myelin index (T1w/T2w), Fibre Orientation Distribution (FOD)10, and tensor-based maps of fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD) were computed using a previously established pipeline11. The DGM masks, FODs, tensor-based maps and myelin maps from all subjects were warped to a tissue-unbiased template12. 10 million (M) streamlines were generated by dynamic seeding13–15 and another 10M streamlines by seeding from the DGM masks14,16–18, which were then combined and optimised using SIFT2 algorithm15,19. The above maps were combined with fibre tracts using the track-weighted imaging (TWI) framework20,21, with 0.7mm isotropic super-resolution22; TWI voxel intensities were computed by taking gaussian-weighted average-metric values along the streamline with FWHM=10 mm. Streamline orientations were measured from the colour channels of the FOD-based directionally-encoded colour (DEC)23 maps. A total of 10 parameters was thus considered for each subject. Components contributing to >5% of the total variance were identified by principal component analysis, and hierarchical k-means clustering was then employed on the principal components to segregate the DGM subregions.RESULTS

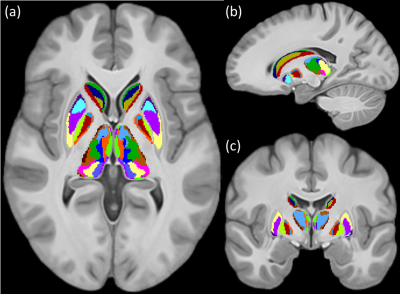

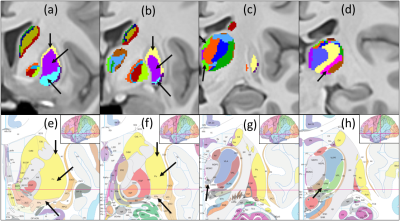

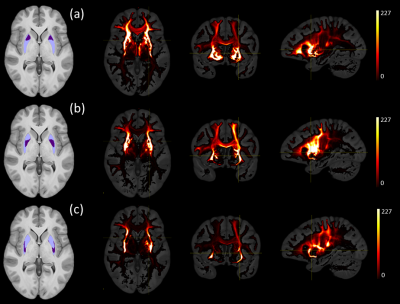

Figures 1 and 2 show the schematic processing pipeline. Figures 3 and 4 show the results obtained from hierarchical k-means clustering, illustrating the parcellations for the cases of caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, nucleus accumbens, and thalamus. Remarkable resemblance was observed among our parcellations and the atlas at the matching coronal locations (Figure 4). Our parcellation identified the fundus of the putamen, the body of putamen, and the ‘external putamen’ (Figure 4a, 4b). The first two sub-structures have distinct neuroanatomy and are recognised as specialised sub-regions within putamen1. The ‘external putamen’ identified by our analysis has only recently been identified by neuroanatomists as having distinct anatomical and functional properties24,25 and is yet to be added to extant human brain atlases. Similarly, the parcels in thalamus (Figure 4c, 4d) can be matched to the corresponding regions in atlas. To note, some of our parcels here represent multiple thalamic regions outlined in the atlas, combined as one (arrows in Figure 4c, 4d). To illustrate the connectivity patterns of our newly defined sub-regions, we isolated the fibre tracks that initiated/terminated at the major clusters of putamen. The track density index (TDI)26 maps computed from these tracks showed overlapping but distinct fibre connectivity patterns (Figure 5).DISCUSSION

These results provide evidence that specialised sub-regions of DGM structures are discernible by unique combination of diffusion properties, WM fibre orientations, and myelin content specific to that region. Additionally, our multi-contrast MRI analysis is sensitive to these attributes and can segregate these regions exclusively from the MRI-derived data without any functional or anatomical prior. Tian et al. has recently demonstrated the topographic organisation of human subcortex using MRI-driven functional connectivity gradients4. Our results show similarities to the major clusters obtained by this work when WM fibre orientation is incorporated. However, the use of TW imaging maps has substantially increased the resolution of our data, which has enabled the identification of many smaller regions within DGM structures, fundus of the putamen for example, which were not identifiable by previous MRI-based parcellations. The two sub-regions identified within the body of putamen indicated distinct fibre connectivity although they belong to the same anatomical structure. The relative evaluations suggest that our results are influenced by the cytoarchitecture and myeloarchitecture (the fundamental basis of atlas) of DGM as well as the fibre orientation within DGM.CONCLUSION

Our detailed delineation of the specialised sub-regions within human subcortex can be directly applied to subject-specific and/or group average MRI dataset. We aim to make the parcellation publicly available along with our population template. The findings from this work may improve the overall understanding of DGM sub-structures in-vivo, the specialised brain networks involving DGM, and allow connectome analysis with higher specificity.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Mai JK, Majtanik M, Paxinos G. Atlas of the Human Brain. Academic Press; 2015.

2. Shen EH, Overly CC, Jones AR. The Allen Human Brain Atlas Comprehensive gene expression mapping of the human brain. Trends Neurosci. 2010;35(12):711-714.

3. Eugenio J, Insausti R, Lerma-usabiaga G, et al. A probabilistic atlas of the human thalamic nuclei combining ex vivo MRI and histology. 2018;183(August):314-326.

4. Tian Y, Margulies DS, Breakspear M, Zalesky A. Topographic organization of the human subcortex unveiled with functional connectivity gradients. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23(November).

5. Van Essen DC, Smith SM, Barch DM, Behrens TEJ, Yacoub E, Ugurbil K. The WU-Minn Human Connectome Project: An overview. Neuroimage. 2013;80:62-79.

6. Sotiropoulos SN, Jbabdi S, Xu J, et al. Advances in diffusion MRI acquisition and processing in the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage. 2013;80:125-143.

7. Glasser MF, Sotiropoulos SN, Wilson JA, et al. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage. 2013;80:105-124.

8. Henschel L, Conjeti S, Estrada S, Diers K, Fischl B, Reuter M. FastSurfer - A fast and accurate deep learning based neuroimaging pipeline. Neuroimage. 2020;219(June):117012.

9. Patenaude B, Smith SM, Kennedy DN, Jenkinson M. A Bayesian model of shape and appearance for subcortical brain segmentation. Neuroimage. 2011;56(3):907-922.

10. Jeurissen B, Tournier JD, Dhollander T, Connelly A, Sijbers J. Multi-tissue constrained spherical deconvolution for improved analysis of multi-shell diffusion MRI data. Neuroimage. 2014;103:411-426.

11. Ali TS, Lv J, Calamante F. Gradual changes in microarchitectural properties of cortex and juxtacortical white matter : Observed by anatomical and diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2022 Dec,88(6):2485-2503.

12. Lv J, Zeng R, Ho MP, D’Souza A, Calamante F. Building a Tissue-unbiased Brain Template of Fibre Orientation Distribution and Tractography with Multimodal Registration. Magn Reson Med. In press, https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.29496.

13. Tournier JD, , F. Calamante and a. C. Improved probabilistic streamlines tractography by 2 nd order integration over fibre orientation distributions. Ismrm. 2010;88(2003):2010.

14. Smith RE, Tournier JD, Calamante F, Connelly A. Anatomically-constrained tractography: Improved diffusion MRI streamlines tractography through effective use of anatomical information. Neuroimage. 2012;62(3):1924-1938.

15. Smith RE, Tournier JD, Calamante F, Connelly A. SIFT2: Enabling dense quantitative assessment of brain white matter connectivity using streamlines tractography. Neuroimage. 2015;119:338-351.

16. Fischl B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage. 2012;62(2):774-781.

17. Tournier JD, Smith R, Raffelt D, et al. MRtrix3: A fast, flexible and open software framework for medical image processing and visualisation. Neuroimage. 2019;202(August):116137.

18. Smith R, Skoch A, Bajada CJ, Caspers S, Connelly A. Hybrid surface-volume segmentation for improved anatomically-constrained tractography. Published online 2020.

19. Calamante F. The seven deadly sins of measuring brain structural connectivity using diffusion MRI streamlines fibre-tracking. Diagnostics. 2019;9(3).

20. Calamante F. Track-weighted imaging methods: extracting information from a streamlines tractogram. Magn Reson Mater Physics, Biol Med. 2017;30(4):317-335.

21. Pannek K, Mathias JL, Bigler ED, Brown G, Taylor JD, Rose SE. The average pathlength map: A diffusion MRI tractography-derived index for studying brain pathology. Neuroimage. 2011;55(1):133-141. 22. Calamante F, Tournier JD, Smith RE, Connelly A. A generalised framework for super-resolution track-weighted imaging. Neuroimage. 2012;59(3):2494-2503.

23. Dhollander T, Smith RE, Tournier JD, Jeurissen B, Connelly A. Time to move on: an FOD-based DEC map to replace DTI’s trademark DEC FA. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med. 2015;23(June):1027.

24. Mehlman ML, Winter SS, Taube JS. Functional and anatomical relationships between the medial precentral cortex, dorsal striatum, and head direction cell circuitry. II. Neuroanatomical studies. J Neurophysiol. 2019;121(2):371-395.

25. Devan BD, Hong NS, McDonald RJ. Parallel associative processing in the dorsal striatum: Segregation of stimulus-response and cognitive control subregions. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;96(2):95-120.

26. Calamante F, Tournier JD, Jackson GD, Connelly A. Track-density imaging (TDI): Super-resolution white matter imaging using whole-brain track-density mapping. Neuroimage. 2010;53(4):1233-1243.

Figures