1358

Investigations of T1 Anisotropy in ex-vivo White Matter using a Tiltable Coil1Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig, Germany, 2Department of Physics, Leipzig University, Leipzig, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Relaxometry, White Matter, T1 Anisotropy WM

In general, a broad consensus exists that dipolar couplings between water protons and motional restricted macromolecules are prominent modulators of longitudinal relaxation in WM. Recent studies demonstrate anisotropic relaxation in human white matter (WM) in dependence of the fibre-to-field orientation. Our approach for further investigations of such effects overcomes previous limitations, in particular, sample reorientations for a direct demonstration of orientation effects, which were missing in earlier studies. Samples of ex-vivo WM tissue of pig brain yielded slightly reduced spin-lattice relaxation times by 1-2% around an angle of 40° between the main fibre direction and B0.Introduction

Recent research has demonstrated an anisotropy of longitudinal relaxation times in human brain in dependence of the fibre-to-field angle (θFB), especially in white matter tracts with a high degree of structural order1,2,3. Noticeably, some studies showed a broad maximum of T1 (up to 7% above the mean) around a position of θFB≈50°, which might be field-dependent1, others proposed a decrease in T1 with increasing angle2. This discrepancy between previous in vivo results calls for further research that (i) validates orientation-dependent T1 changes in white matter with a well-defined experimental strategy and (ii) yields further information about the underlying mechanism. Besides differences in T1 mapping protocols4,5 restrictions to vary the head orientation in human MRI need to be considered. Consequently, conclusions about orientation effects have been based on comparisons of different fibre tracts rather than reorienting the sample in the magnetic field.Methods

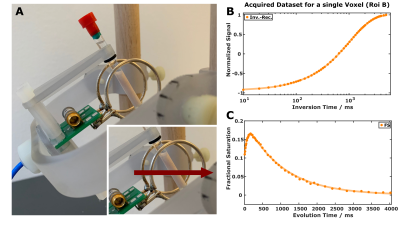

Sample preparation: Fresh pig brains were obtained from a local slaughterhouse with a short post-mortem delay (<6h) and immersed in cold phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS, pH 7.4). Small cylindrical pieces (<25mm) of brainstem were carefully dissected and placed in 5mm NMR tubes filled with Fomblin.MR experiments: Data were acquired on a clinical 3T scanner (MAGNETOM Skyrafit) system at room temperature and at 36°C with a custom-made TxRx Helmholtz coil (16mm loop radius and spacing; Figure 1). It permits free adjustment of the sample orientation without changing the coil properties (e.g., tuning/matching, SNR, B1 homogeneity, radiation damping). All acquisitions were performed with a 1D readout gradient (0.28mm nominal resolution) utilizing three schemes to prepare the spin system:

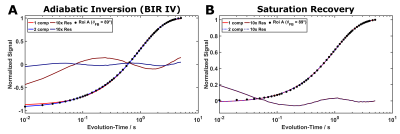

(i) A 5ms (soft) adiabatic 180° pulse (BIR-4) for inversion-recovery experiments (Figure 1B).

(ii) Two adiabatic 90° BIR-4 pulses for saturation-recovery experiments.

(iii) A composite, phase-modulated magnetization-transfer (MT) pulse for transient MT experiments as proposed by van Gelderen6 (Figure 1C). This pulse consisted of 16 subpulses (nominal flip angles of 60°, -120°, 120°, -120° … 120°,-60°) and had a total duration of 6ms. It is assumed that the MT pulse effectively saturates the macromolecular protons and has a minor effect on the hydrogen protons of water6.

Overall, 53 closely sampled evolution times between 10ms and 5s were recorded for all relaxation experiments (i-iii) with sufficient time (TR = 9s) to ensure equilibrium magnetisation before each measurement.

Reconstruction of the diffusion tensor for average fibre direction estimation was based on 1D Stejskal-Tanner measurements with 60 diffusion-sensitising gradient directions (b=1500 s/mm²) . In between, seven data sets were included without diffusion weighting gradients.

Results and Discussion

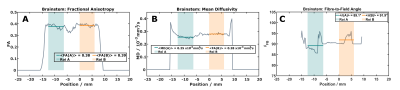

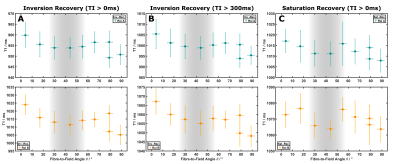

Fractional Anisotropy (FA): In common with previous observations7, FA values were lower in all pig-brain samples compared to highly-ordered human brain regions. The sample selected for extended experiments showed two largely homogeneous regions (~6mm long; Figure 2) with average FA values of 0.38 and 0.39). While this indicates larger dispersions of fibre orientations compared to selected human results, detectable changes in T1 have been proposed for FA > 0.3 in previous work3.Orientation-dependent T1 times: A week orientation dependence of the ‘observed relaxation time’ was robustly obtained in all measurements (Figure 3) indicating a T1 minimum around 40°, which was also replicated when restricting the analysis to inversion times >300ms. Simulations assuming a two-pool model8,9 with magnetization exchange between free water and motional restricted macromolecules suggest minimal contributions from the (faster) intrinsic macromolecular T1 in this range. Further analyses comparing one- and two-component fits of the IR experiment support the assumption of non-mono-exponential recovery (Figure 4), in line with earlier work indicating that multiple proton pools are relevant also in T1 analyses5,10,11. The position of the T1 minimum agrees roughly with the results of Kauppinen et al.1, who, however, reported a T1 maximum. Of note, a maximum of the apparent transverse relaxation time of the macromolecular pool was observed in previous MT experiments and explained by a distinct dipolar absorption lineshape of myelinated fibre bundles. Given that T1 and MT experiments are different expressions of the same cross-relaxation effects, we may assume a common mechanism underlying their orientation dependences. A detailed analysis of these effects requires more complex models (e.g., two or four spin pools) and acquisition strategies, leading to a number of parameters that cannot be easily fitted to the current data. An entirely model-independent verification of orientation dependence is presented in Figure 5, showing an increasing signal offset for single fibre orientations from the acquisition with parallel fibre alignment taken as a reference.

Limitations: While a consistent orientation dependence was observed in all measurements, additional experiments in a sample with lower fibre orientation dispersion (i.e., higher FA) is advocated for presumably increased effects. Further temperature-dependent measurements might also be useful; initial results indicated approx. 10% longer T1 at 36 °C compared to room temperature.

Conclusion

A strategy was implemented to investigate orientation dependence of spin relaxation in fresh or fixed tissue samples on a clinical scanner. It allows precise reorientation of the sample and minimizes confounding effects, such as B1 inhomogeneity or radiation damping.The obtained high precision achieves robust identification of subtle orientation-dependent T1 differences (order of 1-2% at room temperature) with a local T1 minimum around 40°, which are even evident in samples of only moderate fibre alignment.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] Kauppinen RA, Thotland J, Pisharady PK, Lenglet C, Garwood M. White matter microstructure and longitudinal relaxation time anisotropy in human brain at 3 and 7 T. NMR Biomed. 2022; https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.4815.

[2] Schyboll F, Jaekel U, Weber B, Neeb H. The impact of fibre orientation on T1-relaxation and apparent tissue water content in white matter. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phy. 2018; 31(4): 501-510.

[3] Knight MJ, Damion RA, Kauppinen RA. Observation of angular dependence of T1 in the human white matter at 3T. Biomed. Spectrosc. Imaging 2018; 7(3-4): 125-133.

[4] Stikov N, Boudreau M, Levesque IR, Tardif CL, Barral JK, Pike GB. On the Accuracy of T1 Mapping: Searching for Common Ground. Magn. Reson. Med. 2015; 73(2): 514-522.

[5] Manning AP, MacKay AL, Michal CA. Understanding aqueous and non-aqueous proton T1 relaxation in brain. J. Magn. Reson. 2021; 323: 106909.

[6] van Gelderen P, Jiang X, Duyn JH. Rapid Measurement of Brain Macromolecular Proton Fraction With Transient Saturation Transfer MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2017; 77(6): 2174-85.

[7] Fil JE, Joung S, Zimmerman BJ, Sutton BP, Dilger RN, High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging-based atlases for the young and adolescent domesticated pig (Sus scrofa). J. Neurosci. Methods 2021; 354: 109107.

[8] Henkelman RM, Huang X, Xiang QS, Stanisz GJ, Swanson SD, Bronskill MJ. Quantitative interpretation of magnetization transfer. Magn. Reson. Med. 1993; 29(6): 759-766.

[9] Edzes HT, Samulski ET. Cross relaxation and spin diffusion in the proton NMR of hydrated collagen. Nature 1977; 265: 521-523.

[10] Labadie C, Lee J-H, Rooney WD, Jarchow S, Aubert-Frécon M, Springer CS, Jr, Möller HE. Myelin water mapping by spatially regularized longitudinal relaxographic imaging at high magnetic fields. Magn. Reson. Med. 2014; 71: 375-387.

[11] Barta R, Kalantari S, Laule C, Vavasour IM, MacKay AL, Michal CA. Modeling T1 and T2 relaxation in bovine white matter. J. Magn. Reson. 2015; 259: 56-67.

[12] Pampel A, Müller DK, Anwander A, Marschner H, Möller HE. Orientation dependence of magnetization transfer parameters in human white matter. NeuroImage 2015; 114: 136-146.

Figures

Figure 1: Experimental setup with the tiltable Helmholtz coil and a specimen from fresh pig brainstem inside an NMR tube (A). Red arrows indicate the orientation of B0. High-quality data are obtained with IR (B) and transient MT (C) experiments including acquisitions with minimal evolution times.

Figure 2: Results from 1D diffusion tensor imaging (60 directions) with the sample aligned with the scanner’s physical y-direction. The selected two regions of interest are indicated by the shaded areas. Both are characterized by similar FA (A) and mean diffusivity (B). The main fibre direction (C) is approximately parallel to the long axis of the NMR tube.

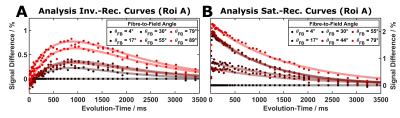

Figure 4: Fits of the data from inversion (A) and saturation-recovery (B) experiments. Deviations for mono-exponential fitting are visible (red solid lines) and also evident in the residuals from both curves. Improvements obtained with bi-exponential fitting (blue lines; long T1 ≈994ms / short T1 ≈79ms) are evident, particularly for the IR curve.