1328

Development and Validation of a Radiomics Model in Differentiating Sinonasal Mucosal Melanomas from Sinonasal Lymphomas1Shanghai Key Laboratory of Magnetic Resonance, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2Department of Radiology, Eye & ENT Hospital of Shanghai Medical School, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, 3MR Scientific Marketing, Siemens Healthcare, Shanghai, China, 4Department of Radiology, Shanghai Cancer Center of Shanghai Medical School, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, 5Department of Radiology, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, FuZhou, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Head & Neck/ENT, Multimodal

Sinonasal mucosal melanomas (SNMM) are clinically more aggressive than its cutaneous counterpart and presented markedly poor prognosis. To differentiate sinonasal melanomas from sinonasal lymphomas, a radiomics model was built using features from multi-parametric MRI, including T1-weighted imaging (T1WI), T2 weighted imaging (T2WI), DWI and C-T1WI. In this multicenter retrospective study, 189 patients diagnosed with SNMMs or sinonasal lymphoma were enrolled from three institutions. The proposed model achieved AUCs of 0.884 and 0.870 in the internal and external validation set, respectively.Introduction

Sinonasal mucosal melanomas (SNMM) are the most common phenotype of mucosal melanoma that originates from the mucosal melanocytes of the sinonasal system1. SNMMs are clinically more aggressive than its cutaneous counterpart and presented markedly poor prognosis with 5-year overall survival rate less than 30%2,3. On MRI, characteristic hyper-intense on pre-contrast T1 weighted imaging (T1WI) and hypo-intense on T2 weighted imaging (T2WI) have been reported to be caused by melanin or hemorrhage and highly suggested melanomas1,4 but were absent in quite a few SNMMs as previously reported5. As far as we know, how radiomics based on multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) would perform in the differentiation of SNMMs from sinonasal lymphomas (SNL) has not been reported. The purpose of our study was to develop an MRI radiomics model and investigate its value and efficiency in the preoperative differentiation between the two entities.Methods

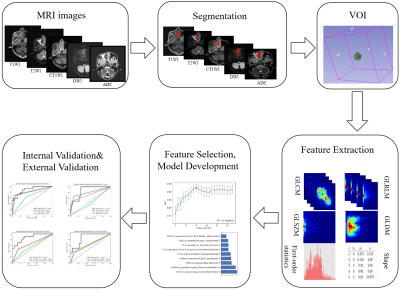

The workflow is shown in Figure 1. A total of 158 patients were enrolled in institution 1, were split into a training set of 111 patients (53 SNMM/58 SNL), and an internal validation set of 47 patients (24 SNMM/23 SNL) for the internal validation set. Twenty-three SNL patients and 8 SNMM patients were enrolled from institution 2 and institution 3 respectively, and they were combined for external validation. The MRI protocol included T1-weighted imaging (T1WI), T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), C-T1WI, and DWI. Patients were scanned on different scanners, including 1.5T and 3T systems from Siemens Healthcare and GE. Lesion contours was segmented by a junior radiologist with 4 years’ experience in head and neck imaging with the guidance of an experienced radiologist with 29 years’ experience in the head and neck imaging. Another senior radiologist with 27 years’ experience segmented all the lesions independently.For structural MRI (T1WI, T2WI) images, contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) was used to enhance and harmonize local image contrast. For each MRI sequence, resegment was used with a relative range [0, 0.995] as suggested by Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative (IBSI)6. For each sequence, IBSI compliant features were extracted with PyRadiomics (version 3.0.1)7 and used to build a single-sequence model. We tried different combinations of different normalization (mean, minmax and z-score), feature selection algorithms (recursive feature elimination (RFE) and Relief), and logistic regression (LR) to find the best combination for the differential diagnosis. Five-fold cross validation over the training data was used for model selection and hyperparameter tuning. Changes of the average cross-validation AUC (CV-AUC) with the number of features was drawn and the model with the highest average CV-AUC was selected. Finally, we combined features retained in single-sequence models to build the combined mpMRI model.

We utilized an open-source software, FeatureExplorer (FAE, ver. 0.5.2)8, to implement the model building mentioned above.

Result

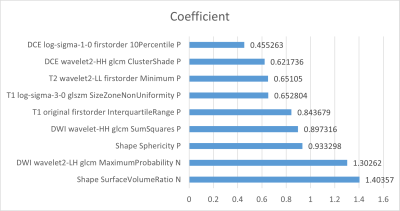

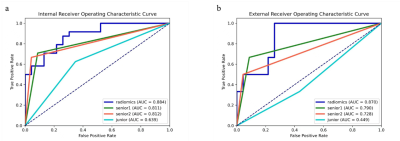

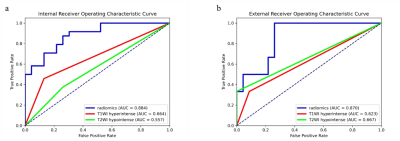

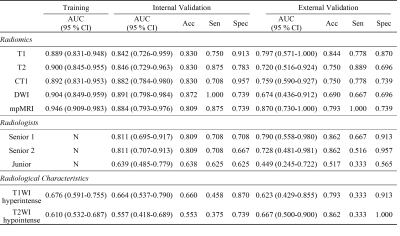

In all radiomics models, the combined mpMRI model achieved the best performance with the highest AUCs of 0.884 [95% CI: 0.793, 0.976] and 0.870 [95% CI: 0.730, 1.000] in the internal and external validation sets, respectively. The weight coefficients of selected features in the radiomics signature were shown in Figure 2. All patients were independently diagnosed by one junior and two senior radiologists (Figure 3). At the same time, we used two classic MRI image characteristics, T1WI hyperintense and T2WI hypointense, to differentiate SNMM and SNL (Figure 4). The comparison of the performance of the mpMRI model with those of the radiologists and image characteristics were shown in Table 1.Discussion

To differentiate SNMMs from sinonasal lymphomas play a key role in deciding management strategy, as surgical excision is essential for SNMMs while non-surgical therapy is recommended for sinonasal lymphomas. In this retrospective multicenter study, radiomics was used for differentiating SNMMs from sinonasal lymphomas. This study enrolled the largest sample size of MRI of SNMMs and no radiomics investigation has been performed previously for the differentiation of the two entities, as far as we know. Radiomics has been used to differentiate intraocular melanomas and achieved good performance, with AUCs ranging from 0.775 to 0.877 in the test set9. However, only internal test set was used. In this study, radiomics models were validated with both internal and external set and demonstrated to be robust across heterogeneous imaging acquisition protocols among different institutions. Our radiomics model demonstrated performance higher than those of characteristic imaging features widely used in the diagnosis for SNMM patients1, and comparable to those of senior radiologists, implying the potential use of mpMRI radiomics models to differentiate SNMM and SNL in real clinical settings.The major limitation of this study is the relatively small external validation set, for which we are still collecting more data from other institutions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study showed that an mpMRI radiomics model using features from T1WI, T2WI, C-T1WI and DWI images demonstrated a good diagnostic performance in differentiating SNMM from SNL and has the potential to be used to help improve the preoperative diagnosis and treatment planning of patients.Acknowledgements

This project is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (61731009, 81771816) and the Open Project of Shanghai Key Laboratory of Magnetic Resonance.

This project is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (61731009, 81771816), the Open Project of Shanghai Key Laboratory of Magnetic Resonance, and the "Excellent doctor-Excellent Clinical Researcher" Project of Eye and ENT Hospital, Fudan University (Grant number: SYA202007)

References

1. Wong V K, Lubner M G, Menias C O, et al. Clinical and imaging features of noncutaneous melanoma[J]. American Journal of Roentgenology, 2017, 208(5): 942-959.

2. Thompson L D R, Wieneke J A, Miettinen M. Sinonasal tract and nasopharyngeal melanomas: a clinicopathologic study of 115 cases with a proposed staging system[J]. The American journal of surgical pathology, 2003, 27(5): 594-611.

3. Dauer E H, Lewis J E, Rohlinger A L, et al. Sinonasal melanoma: a clinicopathologic review of 61 cases[J]. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 2008, 138(3): 347-352.

4. Kim Y K, Choi J W, Kim H J, et al. Melanoma of the sinonasal tract: value of a septate pattern on precontrast T1-weighted MR imaging[J]. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 2018, 39(4): 762-767.

5. Kim S S, Han M H, Kim J E, et al. Malignant melanoma of the sinonasal cavity: explanation of magnetic resonance signal intensities with histopathologic characteristics[J]. American journal of otolaryngology, 2000, 21(6): 366-378.

6. Zwanenburg A, Leger S, Vallières M, et al. Image biomarker standardisation initiative. 2016[J]. ArXiv161207003 Cs, 2021.

7. Van Griethuysen J J M, Fedorov A, Parmar C, et al. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype[J]. Cancer research, 2017, 77(21): e104-e107.

8. Song Y, Zhang J, Zhang YD, Hou Y, Yan X, Wang Y, et al. FeAture Explorer (FAE): A tool for developing and comparing radiomics models. PLoS One. 2020;15(8): e0237587.

9. Su Y, Xu X, Zuo P, et al. Value of MR-based radiomics in differentiating uveal melanoma from other intraocular masses in adults[J]. European Journal of Radiology, 2020, 131: 109268.

Figures