1325

AI-based Single-Click Cardiac MRI Exam: Initial Clinical Experience and Evaluation in 44 Patients

Jens Wetzl1, Seung Su Yoon1, Michaela Schmidt1, Alexander Haenel2, Alexandra-Bianca Weißgerber2, Jörg Barkhausen2, and Alex Frydrychowicz2

1Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 2Klinik für Radiologie und Nuklearmedizin, Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein Campus Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany

1Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 2Klinik für Radiologie und Nuklearmedizin, Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein Campus Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Cardiovascular, Workflow

We propose an Artificial Intelligence-based single-click cardiac MR exam to support technicians and increase standardization and repeatability of cardiac exams, which we evaluate in a clinical setting with 44 patients. Automations include setting of the isocenter position, slice planning in standard and cardiac orientations, adjustment volume and inversion time. Clinical sequences that can be acquired without manual planning include CINE, STIR, T1 mapping, 3D MRA and LGE. 91% (n=40) of the acquisitions could be completed without manual operator intervention, with the majority (n=3) of failed cases caused by abnormal heart geometries leading to inadequate slice planning.Introduction

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) exams necessitate a high level of patient-specific planning and thus require particular qualifications for the technicians performing them. Artificial intelligence (AI) supported automation could help to alleviate problems such as short-staffing, the need for specialized training, and to increase standardization and repeatability of CMR exams. Hence, we propose a prototype system, the AI Cardiac Scan Companion (AICSC), for the acquisition of CMR exams. Here, we evaluated it prospectively in a clinical setting with 44 patients referred for evaluation of structural heart disease.Methods

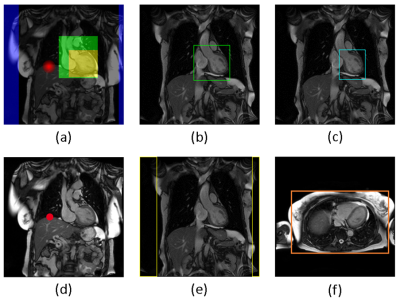

AICSC design. AICSC comprises several modules that automatically execute planning tasks typically performed manually by the technician. Figure 1 illustrates typical protocols acquired during a CMR exam and where automations are applied.AutoPositioning is based on the segmentation of coronal/transversal localizer images to detect bounding boxes of the arms, left ventricle and whole heart (see Figure 2), as well as a liver dome landmark. A UNet1 model was trained in supervised fashion based on annotations of 200 patients and split into 80% training/10% validation/10% test. Annotations were provided by a technician with 23 years of CMR experience. The isocenter was set to the transversal center of the detected left ventricle, the adjustment volume to the detected whole heart bounding box. The center of the whole-heart bounding box was used to position the slice groups for subsequent scans centered at the heart, see Figure 1.

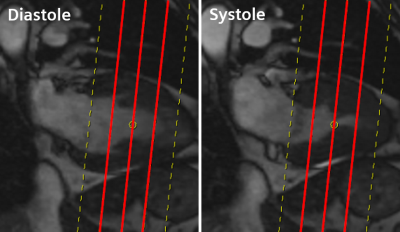

The existing Cardiac DOT Engine2 functionality of the scanner was used for slice planning of the long (LAX) and short-axis (SAX) orientations. A modification in the prototype allows the planning of the 3 representative SAX slices to be based on the “3-out-of-5” rule, e.g. for T1 mapping. To do so, mitral valve and apex landmarks in the end-systolic phase of the 2CH/4CH CINE images are used to plan 5 equidistant slices covering base to apex, then using the middle 3 slices (see Figure 3).

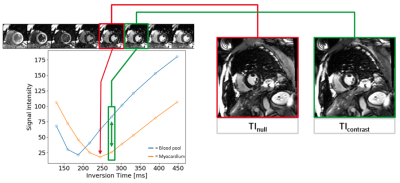

The AutoTI module was previously described3,4 and was used here to automatically select the inversion times (TI) for the LGE acquisitions (see Figure 4). Subsequent LGE scans used fixed increments of the TI to account for the time between TI scout and actual acquisitions.

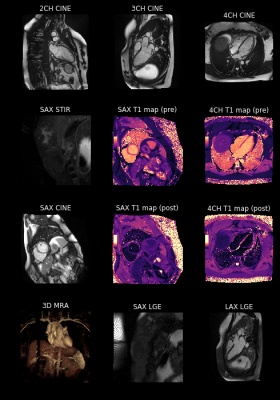

Clinical evaluation. 44 patients (age 52±16, 25 female) referred for structural heart disease evaluation (myocarditis (n=20), cardiomyopathy (n=21), arrhythmogenic foci (n=2)) were prospectively included and examined using the site’s optimized set of clinical protocols following international guidelines, including bSSFP CINE and LGE imaging in LAX (2CH, 3CH, 4CH) and SAX orientation, T2-weighted STIR in SAX, and pre- and post-contrast T1 mapping (4CH + 3 SAX slices). A free-breathing 3D Dixon MRA in coronal orientation was acquired before LGE Imaging using a prototype sequence. Data acquisition was performed on a 1.5T clinical MRI scanner (MAGNETOM Sola, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). The technician recorded the success of the single-click workflow and any reasons for manual intervention. Any safety-relevant confirmations (table movement, SAR, nerve stimulation, contrast agent injection) were still performed manually and not counted as additional clicks. Image quality analysis to detect artifacts, e.g., due to erroneous ECG triggering or poor breath-holding, were outside the scope of this work, the operator manually repeated acquisitions if necessary.

Results

For AutoPositioning, the Dice similarity coefficient on the test set was 94% for the arms and 92% for the left ventricle and whole heart bounding boxes. The Cardiac DOT Engine and AutoTI modules were not modified from their previously published versions, so no separate evaluation was performed.Of the 44 patients scanned using the AICSC, 91% (n=40) were performed successfully without further planning interventions by the technician. In n=3 cases, anatomical deviations lead to incorrect slice planning. In n=1 case, the inversion time selected by AutoTI was incorrect due the large scar size. The patient collective showed a heterogeneous range of left-ventricular size and function (LVEDV 194±111ml, range 85-652ml; LVEF 48±15%, range 17-67%), heart rate (75±19bpm) and included patients with sternal cerclage (n=3), artificial valve (n=2) and event recorder (n=1). The table time was 40±9min, range 24-59. Representative results for a patient are shown in Figure 5.

Discussion

AutoPositioning showed good performance in the individual evaluation and worked in all cases of the prospective evaluation. The success rate of 91% is a very promising step towards being able to perform complex automated CMR exams. Slice planning in deviating anatomies was the most common cause of failure. A modification of the AutoTI algorithm to address a potential source of error in the presence of large scars is subject of ongoing work, as are automated mechanisms for the detection of ECG trigger artifacts and poor breath-holding. To address cases where an automated examination fails, a possible scenario is remote supervision by a technician with a high level of domain knowledge in cardiac imaging.Examination times could be shortened by removing the SAX STIR (~7min) and 3D MRA (~5min) if not clinically necessary. Furthermore, Compressed Sensing CINE could considerably reduce acquisition times, allowing a 20–30-minute cardiac exam.

Conclusion

The initial clinical experience using AICSC for automated cardiac MRI is very promising and seems well-suited for scanning in situations without specifically trained technicians or for follow-up scanning such as in clinical scientific studies.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- Ronneberger O. et al. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. MICCAI 2015, volume 9351.

- Lu X. et al. Automatic view planning for cardiac MRI acquisition. MICCAI 2011;14(Pt 3):479-86.

- Yoon S. et al. A Robust Deep-Learning-based Automated Cardiac Resting Phase Detection: Validation in a Prospective Study. International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) 28th Annual Meeting & Exhibition (2020)

- Yoon S. et al. Validation of a Deep Learning based Automated Myocardial Inversion Time Selection for Late Gadolinium Enhancement Imaging in a Prospective Study. International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) 29th Annual Meeting & Exhibition (2021).

Figures

Figure 1: Overview of the clinical and scout protocols (left) and automation algorithms (right). The black arrows indicate inputs to the algorithms. The green, purple and blue arrows show which protocol settings are automatically adapted.

Figure 2: AutoPositioning detects anatomical structures by segmentation/regression. (a) shows an overlay of the segmentation/regression ground truth on a localizer, different colors denoting different channels. (b) shows the detected whole-heart bounding box, (c) the left ventricle bounding box, (d) the position for the diaphragm navigator, (e) the boundaries of the arms and (f) the extent of the thorax (based on simple intensity thresholding).

Figure 3: The short-axis subset slices are determined by detecting the mitral valve insertion points and LV apex in systole on 2- or 4-chamber long-axis CINE imaging, then planning 5 equidistant slices to cover the short-axis from base to apex and finally removing the most basal and most apical slice to end up with the three short-axis subset slices.

Figure 4: AutoTI determines appropriate inversion times from TI scout series by first segmenting the myocardium and left-ventricular blood pool. The average signal intensity in these ROIs is then plotted against the inversion time. The inversion time with the lowest myocardial signal intensity, TInull, and an inversion time within a small window after TInull where the contrast between myocardium and blood pool is maximized, TIcontrast, are selected.

Figure 5: Overview of all diagnostic sequences acquired during the single-click CMR exam for one representative patient. The short-axis STIR and LGE stacks only show every second slice and the short-axis CINE only one central slice of the entire acquired stack for brevity of the animation. The 3D MRA is displayed as a volume rendering.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1325