1304

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health in 70-year-olds: a population-based ASL study1Radiology & Nuclear Medicine, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2Amsterdam Neuroscience, Brain Imaging, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 3MRC Unit of Lifelong Health at Ageing at UCL, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 4Neuroradiological Academic Unit, Department of Brain Repair and Rehabilitation, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, United Kingdom, 5Dementia Research Centre, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, United Kingdom, 6Queen Square Institute of Neurology and Centre for Medical Image Computing, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 7Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf, Institute of Radiopharmaceutical Cancer Research, Dresden, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Arterial spin labelling

While mid-life cardiovascular pathology may lead to late-life cognitive decline, our understanding of the role of cerebrovascular health as an intermediate biomarker is limited. We explored the association between cardiovascular health biomarkers and cross-sectional and longitudinal cerebrovascular health assessed by ASL MRI in Insight46, a well-characterised cognitively normal population-based sample.

We found several cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between blood pressure and CBF. These findings suggest that the effects of BP on cerebrovascular health can be imaged with ASL perfusion MRI, possibly offering opportunities to prevent or intervene before cognitive decline sets in.

Introduction

Increasing evidence suggests that both cerebrovascular and cardiovascular pathology play a major role in accelerating cognitive decline in normal aging1 and dementia2–4. Current cerebrovascular health parameters, for example white matter hyperintensities (WMH), are rather indirect and static. Arterial Spin Labelling (ASL) perfusion MRI is a promising non-invasive tool for the early detection of hemodynamic risk factors for cognitive impairment. However, our understanding of how cerebrovascular health is related to cardiovascular health is limited.The neuroimaging sub-study ‘Insight46’ of the 1946 British National Survey of Health and Development provides a unique opportunity to study the association between cerebrovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors using ASL MRI. Participants born in the same week of March 1946 have had cardiovascular phenotyping across the life course. Participants underwent multi-modal brain MRI at age 70, and detailed cognitive and cardiovascular assessments5. Multi-modal brain MRI was repeated after 2.5 years.

We explored the association between cardiovascular health biomarkers and cross-sectional and longitudinal cerebrovascular health assessed by ASL MRI in a cognitively normal population-based sample.

Methods

Study-design/data3D T1-weighted, 3D FLAIR, and 3D whole-brain pseudo-continuous ASL (bolus length = 1800ms; post-labelling delay = 1800ms) data were acquired in 241 participants (52.7% female, age: 70.6±0.7 years) on a 3T Siemens Biograph mMR scanner. Clinical data included systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), pulse pressure (PP), Framingham Risk Score (FRS), and Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE).

Image processing

MRI scans were processed with the ExploreASL6. All images were registered to T1w and spatially normalised to MNI. Grey matter (GM), white matter (WM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were segmented from the T1w image. ASL-derived partial volume-corrected cerebral blood flow (CBF) and the spatial Coefficient of Variation (sCoV) were obtained in whole-brain GM and WM.

Statistical analyses

Cross-sectional relationships between CBF, sCoV, and the clinical data were assessed using linear regression modelling. Longitudinal change in CBF, sCoV, and the baseline cardiovascular biomarkers were assessed using linear mixed-effects modelling. To account for the use of BP-lowering medication, 10 mmHg was added to the systolic and diastolic blood pressures for those who were treated7. All analyses were adjusted for sex if appropriate. For statistically significant associations, interaction effects were tested post-hoc as well.

Results

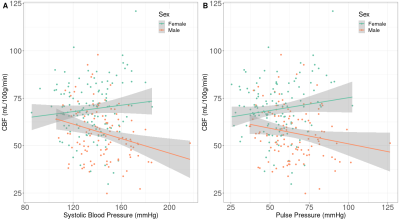

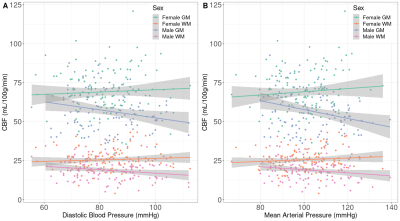

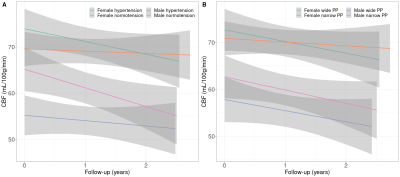

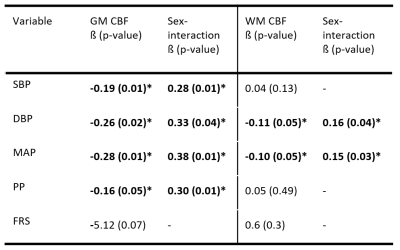

Sex differences were found in baseline SBP (p<0.01), PP (p<0.01), FRS (p<0.01), and both baseline and longitudinal GM and WM CBF/sCoV (p<0.01; Table 1).Statistically significant associations (Figure 1, 2) were found between SBP and GM CBF, DBP and GM CBF, DBP and WM CBF, MAP and GM CBF, MAP and WM CBF, and PP and GM CBF (p<0.05; Table 2). The BP associations were weaker if they were not adjusted with the 10 mmHg BP medication addition (data not shown). No associations with sCoV were found (p>0.05, data not shown). The longitudinal GM CBF changes were only predicted by SBP (ß=-029, p<0.01) and PP (ß=-0.24, p=0.02) (Figure 3).

Discussion

Associations were found between several blood pressure parameters (SBP, DBP, MAP and PP) and whole brain GM and WM CBF, showing the potential for ASL MRI to investigate the link between cerebrovascular and cardiovascular health.Interestingly, GM CBF associations were found with all BP measurements, whereas WM CBF only showed relationships with DBP and MAP. This might suggest that WM is less sensitive to fluctuations in blood pressure over the cardiac cycle than GM, or that WM CBF is a less sensitive biomarker because of its poor SNR relative to GM CBF. Surprisingly, sCoV was not related to any of the cardiovascular biomarkers. As sCoV is a surrogate of arterial transit time8, this suggests that major vascular insufficiency may not always occur in normal aging or when blood pressure-related alterations are present, in contrast to other studies9.

The longitudinal associations showed interesting differences between sexes. Whereas hypertensive (SBP>140mmHg) males had lower GM CBF on baseline compared to normotensive (SBP<140mmHg) males, which is in agreement with the literature10the opposite was found for females. Furthermore, the longitudinal decrease of GM CBF was lower in hypertensive males compared to normotensive males, and again the opposite was found females. Except for a similar longitudinal decrease of GM CBF between male wide PP (>60mmHg) and narrow PP (<60mmHg) groups, similar differences in baseline and trends between males and females were found for GM CBF and PP. This suggests that females with hypertension may still be in a compensatory stage, whereas males with hypertension have passed this stage. However, this needs to be investigated further.

Conclusion

The Insight46 population is cognitively unimpaired and shows a healthy cerebrovascular status, as measured by ASL-derived CBF and sCoV. Relationships between cardiovascular biomarkers and regional cross-sectional and longitudinal CBF were found. These findings suggest that the effects of BP on the brain can be measured with ASL-derived CBF, possibly offering opportunities to prevent or intervene before cognitive decline sets in.Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the following grants: the Dutch Heart Foundation 2020T049 — MD, JP, and HM — the Eurostars-2 joint programme with co-funding from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (ASPIRE E!113701), provided by the Netherlands Enterprise Agency (RvO) — MS, JP, and HM — and the EU Joint Program for Neurodegenerative Disease Research, provided by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development and Alzheimer Nederland DEBBIE JPND2020-568-106 — JP, HM. LW is supported by The Research Council of Norway (273345, 298646, 300767), the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (2018076, 2019101), the European Research Council under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and Innovation program (802998). FB is supported by the NIHR biomedical research centre at UCLH.

The Insight46 study is principally funded by grants from Alzheimer’s Research UK (ARUK-PG2014-1946, ARUK-PG2017-1946), the Medical Research Council Dementias Platform UK (CSUB19166), the British Heart Foundation (PG/17/90/33415) and the Wolfson Foundation (PR/ylr/18575). Florbetapir amyloid tracer is kindly provided by AVID Radiopharmaceuticals (a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly) who had no part in the design of the study. The National Survey of Health and Development is funded by the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_12019/1, MC_UU_12019/3).

References

1. Pettigrew C, Soldan A, Zhu Y, Cai Q, Wang M-C, Moghekar A, et al. Cognitive reserve and rate of change in Alzheimer’s and cerebrovascular disease biomarkers among cognitively normal individuals. Neurobiol Aging. 2020;88: 33–41.

2. Iturria-Medina Y, Sotero RC, Toussaint PJ, Mateos-Pérez JM, Evans AC, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Early role of vascular dysregulation on late-onset Alzheimer’s disease based on multifactorial data-driven analysis. Nat Commun. 2016;7: 11934.

3. Plassman BL, Williams JW Jr, Burke JR, Holsinger T, Benjamin S. Systematic review: factors associated with risk for and possible prevention of cognitive decline in later life. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153: 182–193.

4. Leritz EC, McGlinchey RE, Kellison I, Rudolph JL, Milberg WP. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Cognition in the Elderly. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2011;5: 407–412.

5. Lane CA, Parker TD, Cash DM, Macpherson K, Donnachie E, Murray-Smith H, et al. Study protocol: Insight 46 – a neuroscience sub-study of the MRC National Survey of Health and Development. BMC Neurol. 2017;17. doi:10.1186/s12883-017-0846-x

6. Mutsaerts HJMM, Petr J, Groot P, Vandemaele P, Ingala S, Robertson AD, et al. ExploreASL: An image processing pipeline for multi-center ASL perfusion MRI studies. Neuroimage. 2020;219: 117031.

7. Sudre CH, Smith L, Atkinson D, Chaturvedi N, Ourselin S, Barkhof F, et al. Cardiovascular Risk Factors and White Matter Hyperintensities: Difference in Susceptibility in South Asians Compared With Europeans. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7: e010533.

8. Mutsaerts HJ, Petr J, Václavů L, van Dalen JW, Robertson AD, Caan MW, et al. The spatial coefficient of variation in arterial spin labeling cerebral blood flow images. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37: 3184–3192.

9. Hafdi M, Mutsaerts HJ, Petr J, Richard E, van Dalen JW. Atherosclerotic risk is associated with cerebral perfusion - A cross-sectional study using arterial spin labeling MRI. Neuroimage Clin. 2022;36: 103142.

10. Tryambake D, He J, Firbank MJ, O’Brien JT, Blamire AM, Ford GA. Intensive blood pressure lowering increases cerebral blood flow in older subjects with hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;61: 1309–1315.

Figures

Table 2 Cross-sectional linear regression analyses between clinical variables and CBF. CBF = Cerebral Blood Flow; DBP = diastolic Blood Pressure; FRS = Framingham Risk Score; GM = Grey Matter; SBP = systolic blood pressure; sCoV = spatial Coefficient of Variation; WM = White Matter.