1271

High Temporal Resolution Blood Oxygen Level Dependent functional MRI.

Martyna Dziadosz1,2,3,4, Tom Hilbert2,5,6, Jérôme Yerly2,6, Matthias Stuber2,6, Matthias Nau7, Micah M. Murray1,2,3,6,8, Eleonora Fornari2,6, and Bendetta Franceschiello2,3,4

1Laboratory for Investigative Neurophysiology (The LINE), Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne (CHUV-UNIL), Lausanne, Switzerland, 2Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 3The Sense Innovation and Research Centre, Lausanne and Sion, Switzerland, 4Institute of Systems Engineering, School of Engineering, HES-SO Valais-Wallis, Sion, Switzerland, 5Advanced Clinical Imaging Technology, Siemens Healthineers International AG, Lausanne, Switzerland, 6CIBM Center for Biomedical Imaging, Lausanne, Switzerland, 7Laboratory of Brain and Cognition, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States, 8Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States

1Laboratory for Investigative Neurophysiology (The LINE), Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne (CHUV-UNIL), Lausanne, Switzerland, 2Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 3The Sense Innovation and Research Centre, Lausanne and Sion, Switzerland, 4Institute of Systems Engineering, School of Engineering, HES-SO Valais-Wallis, Sion, Switzerland, 5Advanced Clinical Imaging Technology, Siemens Healthineers International AG, Lausanne, Switzerland, 6CIBM Center for Biomedical Imaging, Lausanne, Switzerland, 7Laboratory of Brain and Cognition, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States, 8Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, fMRI (task based), hemodynamic response, high temporal resolution, visual cortex

We demonstrate the feasibility and robustness of a new method to measure blood-oxygen-level-dependent functional MRI(BOLD-fMRI) signals at high temporal resolutions(up to 250ms). Whole-brain data at 1x1x1 mm3 were acquired uninterruptedly during a blocked-design ON/OFF visual paradigm(checkerboard vs. grey image). Images were reconstructed with a 4D x-y-z-t dimensions at 2.5s, 1.0s, 500ms and 250ms temporal resolution, allowing to retrieve the expected %signal change(2%) in visual cortices. We also evaluated the effect of compressed-sensing(CS) application in BOLD-fMRI reconstruction schemes, finding that CS improves the obtained signal in the calcarine sulcus(around 23k(a.u) in pixel intensity of BOLD map TCFE corrected vs 10k(a.u)).Introduction

Ever since its invention in the 1990s, Blood-oxygen-level-dependent functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging(BOLD-fMRI) has been successfully employed to map the brain’s cognitive processes1,2. While echo planar imaging(EPI) is the most frequently used method to acquire fMRI data, there is growing interest in being able to record fMRI(and BOLD-fMRI) responses at higher temporal resolution than feasible with conventional EPI3,12. Higher resolution may enable examining rapid changes in the hemodynamic response that are not captured by conventional fMRI models. The method presented here introduces novel fast sampling and the ability to measure(rather than model) the hemodynamic response in BOLD-fMRI with sub-second temporal resolution.Accelerating fMRI has been addressed by multiple-shot 3D EPI4, echo volume imaging5 or simultaneous multi-slice-EPI6 and enabled a whole-brain temporal resolution above 500ms15. Here, we propose a novel approach, where entire brain volumes are obtained at a high temporal sampling rate(28.24ms)7 with a final sub-second temporal resolution of 250ms. Importantly, our method is less prone to classic EPI-like artifacts and more robust to motion, as it employs 3D radial sampling strategies, compressed sensing(CS)8 reconstruction, and data rejection paradigms that enable high-resolution T2* whole-brain imaging7. Moreover, it maintains high spatial resolution and whole-brain coverage, which is critical for its applicability across research domains.

This study successfully used a temporal binning strategy to measure BOLD %signal changes evoked by the hemodynamic response(HR) at three high temporal resolutions: 250ms, 500ms, and 1s. The obtained signal was compared to the known priors from 2.5s temporal resolution. Furthermore, to explore the influence of CS in the retrieval of BOLD-fMRI-like signals, we explored the impact of the number of readouts used for the reconstruction of the BOLD contrast maps.

Methods

Participants and visual stimulation. Twenty healthy humans were scanned on a 3T clinical scanner(MAGNETOM PrismaFit, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using a 64-channel transmit-receive coil with an attached mirror(18° visual field) on which visual stimuli(8Hz flickering checkerboards) were back-projected. The stimulation procedure followed a blocked design(33 trials lasting 40s each: 15s ON phase and 25s OFF phase(full-field grey patch).Acquisition. An uninterrupted gradient recalled echo(GRE) research application sequence with a 3D radial spiral phyllotaxis sampling trajectory9 was used to record the data. This allowed for consistent k-space coverage across all bins. To synchronize the acquisition and the visual stimulation, a Syncbox(Nordic NeuroLab) was used. 46,772 readouts were obtained with TE/TR=25/28.24ms, FoV=192x192x192mm3(1mm3 isotropic resolution), FA=12°, TA=22 min. A high-resolution anatomical T1-weighted volume(MPRAGE, TE/TR=2.43/1890ms, FA=9°, FOV=256x256, 192 slices, VOI=1mm3 isotropic) was obtained as basis to segment the regions of interest(ROIs).

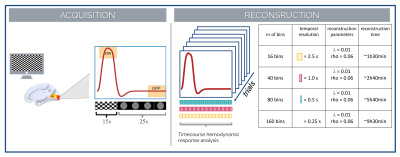

Reconstruction. Images were reconstructed with 4D x-y-z-t dimensions(where t relates to number of bins, Fourier Transform regularization)7 for 16, 40, 80 and 160 bins corresponding to 2.5s, 1.0s, 500ms, and 250ms temporal resolution of the recorded %signal change of the BOLD response, respectively(fig.1, right). Acquired readouts were reconstructed with (total variation regularization along the trial dimension) and without CS, as well as for all and half of the trials. Rigid body transformations to correct motion was estimated using SPM1210 and applied to k-space.

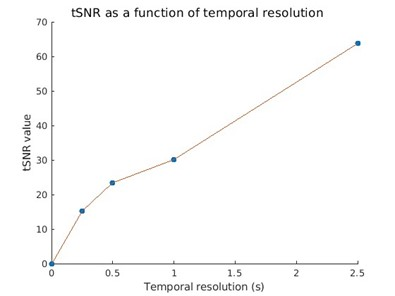

Analysis. Voxels surrounding the calcarine sulcus(i.e., low-level visual cortex) were extracted from T1-weighted-MPRAGE using FreeSurfer11. These volumes were registered onto the 4D-reconstructed image using SPM1210, to extract the average hemodynamic response(%signal change). The %signal change was computed by considering the responses across bins, subtracting, and dividing the mean of this signal. To compare the reconstruction performed at different temporal resolutions, tSNR(mean/standard deviation along t, fig.4) was estimated.

For the CS comparison, an inference at a group level was computed as a paired-t-test (p<0.001, extended threshold of 100 contiguous voxels) for the three different reconstructions.

Results

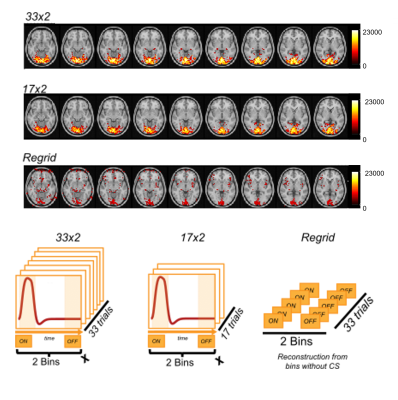

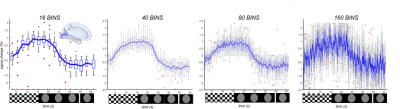

The comparison between reconstructions performed with different number of readouts(46,772 vs. half) and with or without CS shows that the use of CS allows retrieving canonical BOLD-fMRI maps, together with a sharper and more localized signal(fig.3). Moreover, as indicated by the colormap, signal intensity in the visual cortex obtained with CS is higher(around 23k(a.u) in pixel intensity of BOLD map TCFE corrected) than without(~10k(a.u) in pixel intensity of BOLD map). The average hemodynamic response signal obtained for different temporal resolutions in the calcarine ROI is then presented in fig.3. Although the changes in SNR are visible, the %signal change stays around 2%, in agreement with gold standard comparison of %BOLD %signal changes. As expected, the tSNR decreases as temporal resolution rises(fig.4), although even for a temporal resolution of 250ms, the total SNR stays above 10.Discussion/Conclusions

The proposed framework consistently retrieved BOLD %signal change(around 2%) at high temporal resolutions using CS techniques, suggesting that it is widely applicable in research and clinical settings involving fMRI. We retrieved the expected physiological response to visual stimulation in the expected regions(e.g., the calcarine sulcus), and we analyzed changes in tSNR which remained above expected(>10) even for the highest temporal resolution. Furthermore, we show how the use of CS techniques allows to retrieve higher intensity signal changes(~23k(a.u.) in TCFE scale) in comparison with shorter acquisition and without CS application.Given the flexibility and high temporal-spatial accuracy, the proposed acquisition and reconstruction framework opens new possibilities to disentangle the components contributing to the signal, hence moving towards a more quantitative way of measuring BOLD-fMRI signal.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- Ogawa, S., Lee, T. M., Kay, A. R. & Tank, D. W. Brain magnetic resonance imaging with contrast dependent on blood oxygenation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87, 9868–72 (1990).

- Ogawa, S. et al. Intrinsic signal changes accompanying sensory stimulation: functional brain mapping with magnetic resonance imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 89, 5951–5955 (1992).

- Polimeni, J. R., & Lewis, L. D. (2021). Imaging faster neural dynamics with fast fMRI: A need for updated models of the hemodynamic response. Progress in neurobiology, 207, 102174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2021.102174

- Poser BA, Koopmans PJ, Witzel T, Wald LL, Barth M. Three-dimensional echo-planar imaging at 7 Tesla. Neuroimage. 2010; 51:261-266.

- Posse S, Ackley E, Mutihac R, et al. Enhancement of temporal resolution and BOLD sensitivity in real-time fMRI using multi-slab echo-volumar imaging. Neuroimage. 2012; 61:115-130.

- Moeller S, Yacoub E, Olman CA, et al. Multiband multislice GE-EPI at 7 Tesla, with 16-fold acceleration using partial parallel imaging with application to high spatial and temporal whole-brain fMRI. Magn Reson Med. 2010; 63:1144-1153.

- Franceschiello B., Rumac S., Hilbert T., Roy C.W., Degano G., Gaglianese A., Yerly J., Stuber M., Kober T., van Heeswijk R.B., Murray M.M., and Fornari E. A novel free-running framework for Blood Oxygen Level Dependent functional MRI. In Proceedings of the 31th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; 2114

- Lustig, M., Donoho, D., Santos, J. & Pauly, J. Compressed Sensing MRI. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 25, 72–82, DOI:10.1109/MSP.2007.914728 (2008).

- Piccini, D., Littmann, A., Nielles-Vallespin, S. & Zenge, M. O. Spiral phyllotaxis: The natural way to construct a 3D radial trajectory in MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 66, 1049–1056 (2011).

- Andersson, J. et al. Statistical Parametric Mapping: The Analysis of Functional Brain Images. (ACADEMIC PRESS, 2006).

- Fischl, B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 62, 774–781 (2012).

- Toi Hyun P.T. et al. In vivo direct imaging of neuronal activity at high temporospatial resolution. Science 378, 160–168 (2022)

- Mansfield, P.,1977. Multi-planar image formation using NMR spin echoes. J Phys C Solid State Phys 10. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3719/10/3/004.

- Mansfield, P., Harvey, P.R., 1993. Limits to neural stimulation in echo-planar imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 29, 746–758. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.1910290606

- Bollmann S., et al, 2021, New acquisition techniques and their prospects for the achievable resolution of fMRI. Prog Neurobiol, 101936

Figures

Figure 1. Acquisition

and reconstruction scheme. (left) Simulated hemodynamic response corresponding

to the task. (right) Performed reconstruction – 4D reconstruction with

hemodynamic response resolved with 16, 40, 80, 160 temporal bins of 2.5s, 1s,

500ms, 250ms each, respectively. λ and rho refers to parameters used in the

Lagrangian multipliers to reconstruct the images.

Figure 2. Acquired dataset were reconstructed with three different

approaches: with all the readouts (33 trials) and applying

CS (referred to as 33x2), with half of the readouts (and therefore half of the trials,

17) and applying CS (referred to as 17x2) and with all readouts, but without applying

CS regularization (referred to as Regrid). This figure shows, the

difference in hemodynamic response intensity distribution achieved with three

different reconstructions.

Figure 3. Measured

inter-subject percentage signal changes in the calcarine

cortex for reconstruction performed with different temporal resolutions: 2.5s,

1.0s, 500ms and 250ms, respectively. For comparison purposes, the hemodynamic

response function was zoomed to [-2.5, 2.5].

Figure

4. Temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR) depends on bins' temporal resolution.

It was computed as the mean over standard

deviation across the temporal dimension in the ROI calcarine.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1271