1269

Somatosensory-evoked fMRI with chemogenetic modulation reflects behavioral normalization in hypersensitized mice1Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research (CNIR), Institute for Basic Science (IBS), Suwon, Korea, Republic of, 2Medical Imaging AI Research Center, Canon Medical Systems Korea, Seoul, Korea, Republic of, 3Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering,, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), Daejeon, Korea, Republic of, 4Department of Biological Sciences, Korea Advanced Institute for Science and Technology (KAIST), Daejeon, Korea, Republic of, 5Center for Synaptic Brain Dysfunctions, Institute for Basic Science (IBS), Daejeon, Korea, Republic of, 6Department of Biomedical Engineering, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon, Korea, Republic of

Synopsis

Keywords: fMRI (task based), Animals

The fMRI mapping with selective modulation of local neural population at the manipulated region is a powerful approach that can causally link circuit-specific interactions to behavioral performance. However, most fMRI studies combined with chemogenetics were conducted in the resting state, which is difficult to elucidate whether and how differences in functional activity by neuromodulation induce behavioral changes. Here, we demonstrated the effects of fMRI-guided focal chemogenetic modulation on both somatosensory-evoked network and its relevant behaviors in mice.Purpose

Concurrent cell type/circuit-specific modulations and fMRI in animals can provide valuable insights into understanding the causal relationships between neuronal activity and brain-wide network. The neural modulation can be achieved via optogenetics1 and chemogenetics2. These strategies are employed to light-sensitive ion channels or designer receptors exclusively by designer drugs (DREADDs), respectively. fMRI combined with optogenetics typically required chronic intracranial fiber implants to deliver light pulses, which can often cause image artifacts of distortion and signal drops in fMRI studies3. Alternatively, chemogenetics offers the advantage of not requiring fiber implants, and enabling sustained neural modulation with a single drug administration. Most chemogenetic fMRI studies were conducted at rest4,5. However, since resting-state fMRI does not measure functional afferent/efferent circuit processes6, it is difficult to reflect how differences in functional activity due to neuromodulation induce behavioral changes. Therefore, we investigated the effects of fMRI-guided chemogenetic modulation on both somatosensory-evoked network and its relevant behaviors in mice.Materials & Methods

To causally link brain-wide networks to behavioral performance, three different studies were designed: 1) fMRI-guided detection on aberrant somatosensory circuit, 2) sensory-evoked fMRI combined with chemogenetic silencing in the aberrant functional region, and 3) behavior tests.All BOLD-fMRI experiments were performed on 15.2T using single-shot GE-EPI sequence (TR/TE=1000/11.5ms, spatial resolution=132×132×500μm3) under dexmedetomidine-isoflurane anesthesia7. Sensory-sensitized transgenic mice (HT) with autism spectrum disorder (ASD)-risk C456Y heterozygous mutation in the Grin2b gene8 and naïve C57BL/6 mice (WT) were used.

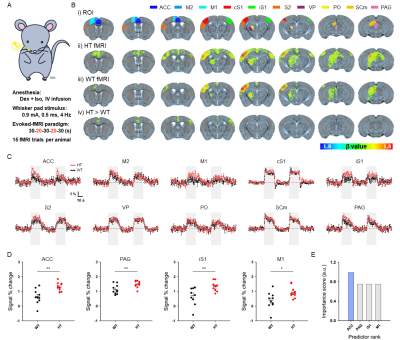

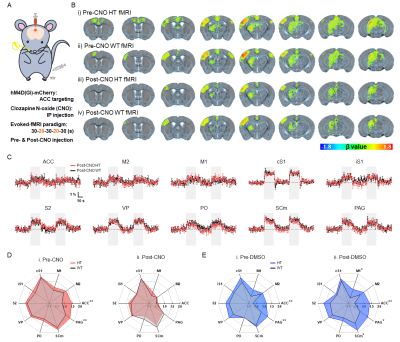

First, we asked which brain regions exhibit abnormal functional activity in HT mice (n=11) compared to WT controls (n=10). For somatosensory activation, the right whisker-pad was electrically stimulated with current intensity of 0.9-mA, pulse width of 0.5-ms, and frequency of 4-Hz. Functional trial consisted of a 30-s prestimulus, 20-s stimulus, 30-s interstimulus, 20-s stimulus, and 30-s post stimulus period, and 15 fMRI trials were obtained for signal averaging (Fig.1A). Next, we investigated whether functional normalization or rescue in HT mice using chemogenetic modulation of the aberrant brain region could be observed in somatosensory-evoked fMRI. To inhibit the excitatory neuronal activity, AAV-CaMKIIα-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry (DREAD virus, ≥ 8.6×1012vg/mL) were injected into the relevant brain region determined from the fMRI-guided experiments. Three-four weeks after the DREAD virus injection, somatosensory-evoked fMRI was repeated before and after 10-mins of clozapine-n-oxide (CNO, 5mg/kg, n=11 each group) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, as control for CNO) injection intraperitoneally (Fig.2A). Finally, to examine whether fMRI findings directly reflect the somatosensory behaviors, three different behavioral tests were performed; Von Frey Test (VFT), thermal place preference test (TPT), and electric foot shock test (EFS) respectively to the evaluate mechanical thresholds for somatosensory stimuli, degrees of thermal place avoidance response, and freezing responses to electrical stimuli.

To estimate the regional specificity of sensory-evoked BOLD changes, fMRI data were spatially normalized onto the mouse brain atlas space9. Time-series data were extracted based on the somatosensory-related ROIs10 (Fig.1B.i) and then the signal changes over the stimulus duration were averaged.

Results

Animal-wise averaged fMRI maps (Fig.1B.ii-iii) and ROI-based fMRI signals (Fig.1C) show that stimulation of the whisker-pad showed stable positive response in the somatosensory pathway, whereas hyperactive fMRI responses were clearly observed in four regions including ACC, PAG, ipsilateral S1, and M1 in sensory-sensitized HT mice (Fig.1D). Among them, ACC was found to be the most aberrant region determined by a minimum redundancy maximum relevance (MRMR)-based feature selection (Fig.1E).With this fMRI-guided regional detection, somatosensory-evoked fMRI was combined with chemogenetic silencing of ACC (Fig.2A). Before CNO injection, the hyperactive regions including ACC were reproducibly observed in HT mice (Fig.2B.i-ii and 2D.i). However, after ACC silencing, HT mice showed a significant DREADD-mediated normalization of fMRI activities within the somatosensory circuit, similar to those levels of WT mice (Fig.2B.iii-iv, 2C, and 2D.ii). We did not observe the similar effects with DMSO injection, confirming that the normalization of fMRI response was well driven by DREADD treatment (Fig.2E).

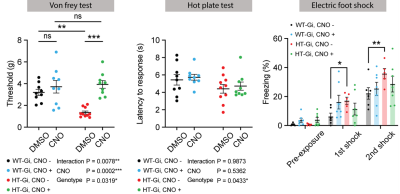

In the behavioral tests (Fig.3), most somatosensory performances including mechanical thresholds for stimuli (VFT) and freezing responses to electrical stimuli (EFS) were significantly returned to a normal level during chemogenetic silencing of ACC in HT mice. The degree of thermal place avoidance response (TPT) was not significant, but slightly changed.

These two independent experiments, fMRI mapping and behavioral tests, indicate that functional circuit-evoked fMRI combined with chemogenetics can measure the behavior-modulating network changes.

Discussion & Conclusion

We examined the effects of chemogenetic circuit-specific silencing on the hyperactivities of the somatosensory network and relevant behaviors using ASD-risk mutant HT mice. The ACC, known for vast top-down modulatory function10, was determined as a potential hub involved in the hyperactivities in the genetic model. Chemogenetic inhibition of ACC lead to normalization of the responses in both somatosensory fMRI and behavior experiments in HT mice. Sensory fMRI with chemogenetic manipulation is a valuable tool for monitoring the modulation of aberrant brain networks leading to change the behavioral performance. The main benefit of the tonic activation of DREADD receptors via chemogenetics over optogenetics is to perform prolonged inactivation of ACC, which circumvents the need for optic fiber placement and possible heating issues11. Therefore, our findings underscore the potential utility of task-fMRI-guided chemogenetic approaches to observe changes in the functional network directly linking to behaviors and furthermore to facilitate translatable manipulation for disease treatment.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by IBS-R015-D1.

References

1. Deisseroth K. Optogenetics. Nat Methods. 2011;8(1):26-29.

2. Roth BL. DREADDs for Neuroscientists. Neuron. 2016;89(4):683-694.

3. Jung WB, Jiang H, Lee S, Kim SG. Dissection of brain-wide resting-state and functional somatosensory circuits by fMRI with optogenetic silencing. PNAS. 2022;119(4):e2113313119.

4. Zerbi V, Floriou-Servou A, Markicevic M, et al. Rapid Reconfiguration of the Functional Connectome after Chemogenetic Locus Coeruleus Activation. Neuron. 2019;103(4):702-718.e5.

5. Rocchi F, Canella C, Noei S, et al. Increased fMRI connectivity upon chemogenetic inhibition of the mouse prefrontal cortex. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1056.

6. Drew PJ, Mateo C, Turner KL, Yu X, Kleinfeld D. Ultra-slow Oscillations in fMRI and Resting-State Connectivity: Neuronal and Vascular Contributions and Technical Confounds. Neuron. 2020;107(5):782-804.

7. You T, Im GH, Kim SG. Characterization of brain-wide somatosensory BOLD fMRI in mice under dexmedetomidine/isoflurane and ketamine/xylazine. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13110.

8. Shin W, Kim K, Serraz B, et al. Early correction of synaptic long-term depression improves abnormal anxiety-like behavior in adult GluN2B-C456Y-mutant mice. PLoS Biol. 2020;18(4):e3000717.

9. Oh SW, Harris JA, Ng L, et al. A mesoscale connectome of the mouse brain. Nature. 2014;508(7495):207-214.

10. Lee JY, You T, Lee CH, et al. Role of anterior cingulate cortex inputs to periaqueductal gray for pain avoidance. Curr Biol. 2022;32(13):2834-2847.e5.

11. Schmid F, Wachsmuth L, Albers F, Schwalm M, Stroh A, Faber C. True and apparent optogenetic BOLD fMRI signals. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(1):126-136.

Figures

Figure 1. Evoked fMRI-guided detection of aberrant somatosensory network.

A. Schematic of somatosensory-evoked fMRI in mice

B. i) Allen Mouse Brain Atlas–based somatosensory ROIs, ii-iii) group-averaged fMRI maps in ASD-risk mutant HT mice and WT controls (corrected p < 0.01), and iv) group-wise differences (corrected p < 0.01)

C. fMRI time courses of somatosensory network

D. Hypersensitive regions in HT mice (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; independent t-test)

E. Feature selection to determine the potential hub for chemogenetic modulation

Figure 2. Chemogenetic modulation of ACC normalizes somatosensory fMRI responses.

A. Schematic of chemogenetic somatosensory-evoked fMRI in mice

B. group-averaged fMRI maps in HT and WT mice with/without chemogenetic modulation

C. fMRI time courses of somatosensory network with chemogenetic modulation

D. fMRI signal changes during somatosensory stimulation with/without chemogenetic modulation

E. DMSO control experiments to verify the DREADD effects

Figure 3. Somatosensory abnormalities alleviated by chemogenetic modulation of ACC.

A. Electronic Von Frey test to measure the mechanical threshold with/without chemogenetic modulation

B. Thermal place preference test to measure the time on warm floor with/without chemogenetic modulation

C. Electric foot shock test to measure the freezing time with/without chemogenetic modulation

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisions.