1264

Time-of-Day Analysis of Brain Sodium TSC Maps1School of Biomedical Engineering, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2Imaging Research Centre, St. Joseph's Healthcare, Hamilton, ON, Canada, 3Department of Radiology, Children's Hospital Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States, 4Electrical and Computer Engineering, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada, 5Department of Radiology, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Quantitative Imaging, Non-Proton, Sodium, Variability, Brain, Circadian, Human

Previous investigations into brain sodium imaging have avoided the potential of variability due to circadian effects. Thus, in a pilot study we investigated whether time-of-day contributes to tissue sodium concentration (TSC) variance. Three TSC maps were acquired from 7 subjects, at three different times of day (8:00, 16:00, 22:00). Each TSC map was segmented into 10 ROIs before being analyzed using ANOVA with SNR and signal linewidth as added covariates. Time-of-day was a significant source of variance as was spectral linewidth. Between subject variance and SNR were not significant factors in the model.

Introduction

There have been a few inquiries into the repeatability/reproducibility of sodium MRI, however one potential key source of variance, time-of-day, is typically fixed1,2. Why this is likely not valid lies in reports of sodium concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) having temporal fluctuations that follow a subject’s circadian rhythm as mentioned in the previous studies3. This daily variation could in turn impact brain tissue sodium concentration (TSC). Because of the temporal variation seen in the CSF sodium concentration, we investigated whether a circadian component was detectable in brain TSC. Due to the low concentration of brain sodium, the investigation also included signal SNR and linewidth as potential contributing covariates to the model.Methods

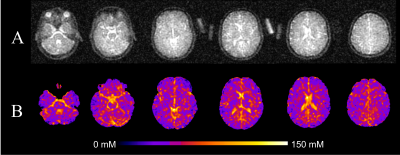

In a study approved by our local research ethics board, healthy volunteers (n=7, 5 male, aged 26.6 ± 3.4yrs) were scanned using a GE MR750 Discovery 3T (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) equipped with an 8kW broadband RF amplifier and a home designed/built 16 rung single resonance quad birdcage T/R coil (tuned to 33.786MHz). The sodium protocol consisted of two density adapted radial projection (DA-3DRP: 0.6ms hard pulse, TR=24ms, TE=0.2ms, 240mm FOV with 3.2mm isotropic resolution)4 acquisitions at flip angles 70° and 30°. Two flip angles were used to calculate a TSC map using the variable flip angle (VFA) approach5. The TSC maps were quantified using two 50mL calibrants of 30mM and 80mM NaCl (3% agar) that were included in the imaging FOV alongside the subject for all scans. Figure 1 shows an example of a raw sodium image and its corresponding TSC map. In a separate scan, a single anatomical proton T1-weighted 3D-fSPGR (1mm isotropic, θ=12°, TE=2.1ms, TR=11.4ms, 240mm FOV) was also acquired using a 32-channel head coil for registration and ROI segmentation purposes.Each subject had three scanning sessions: morning (08:00), afternoon (16:00), and night (22:00) over the course of two weeks, with each session consisting of three executions of the sodium protocol, with approximately a 10-minute break between each. This resulted in three TSC maps, per time point, per subject, for a total of 63 TSC maps. Each TSC map was then registered to their respective anatomical image using FSL’s FLIRT6 tool before being warped into Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using FSL’s FNIRT7 to allow between and within subject ROI comparisons. Following registration and spatial warping, TSC maps were segmented into ten ROIs: cerebral white matter, frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, occipital lobe, deep brain grey matter, cerebellum, brainstem, ventricles, and total cerebral grey matter and a mean sodium concentration was calculated for each.

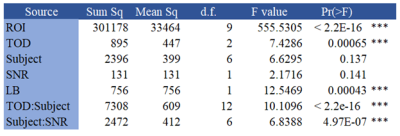

Using R software8 the ROI data was modelled as a linear mixed-effects regression model9 with TSC as the dependant variable, factors ROI and time-of-day as independent variables, and SNR and linewidth as covariates. The goal was to assess for time-of-day effects while considering all other relevant sources of variance. The model also accounted inter-subject and intra-subject variance through repeated measures. Each factor was also compared to a null model (i.e. a model with that factor removed) to see if there were any significant contributions from that factor to the model and only significant factors/covariates/interdependencies were kept. The model was then assessed through ANOVA analysis to determine the significant sources of variance.

Results

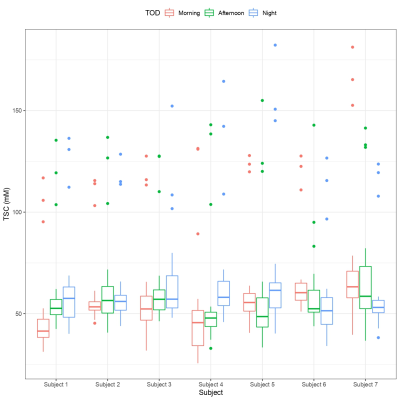

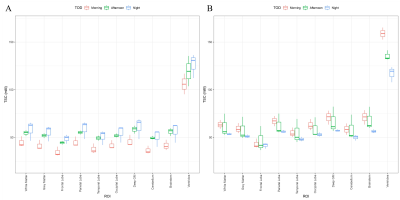

Location of ROI, time-of-day, and linewidth contributed significantly to brain TSC variance (Table 1). Furthermore, there was also significant interaction terms between time-of-day and subject, as well as between subject and SNR. Figure 2 shows the average brain TSC, for each subject, by time-of-day (morning, afternoon, and night). There was a subject-dependency on TSC where subjects 1,3, and 4 had lower morning values and higher at night. Meanwhile subjects 6 and 7 showed the opposite trend, with highest TSC values in the morning and lowest at night. Subjects 2 and 5 had the afternoon as their maximum and minimum, respectively. Figure 3 shows two of the subjects TSC values, as broken down by ROI which reveals the amount of variation in the sodium concentrations due to time-of-day.Conclusions and Discussion

This pilot study shows significant variations in brain TSC maps, when taking into consideration time-of-day. The inclusion of system parameters SNR and linewidth, which are reflective of scan quality, was important in the model. Linewidth was a significant factor as was the interaction term between SNR and subject (Table 1). Taking into consideration the variance of linewidth and SNR there was a notable circadian variation in TSC. Thus, variation between scanning sessions needs to be accounted for, a result which is different from previous sodium variability studies1,2. The results from this pilot study need further exploration. For example, more time points are needed over a 24hr span. Also, more subjects (including more women) would assist in solidifying the results. Lastly behavioral data (night ‘owl’ vs. early ‘bird’), and blood and urine samples could provide a measurement of bodily sodium concentrations which would be helpful in determining correlations between the time-of-day and brain TSC.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] Meyer, M.M., Haneder, S., Konstandin, S., Budjan, J., Morelli, J.N., Schad, L.R., Kerl, H.U., Schoenberg, S.O., Kabbasch, C., 2019. Repeatability and reproducibility of cerebral 23Na imaging in healthy subjects. BMC Medical Imaging 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-019-0324-6

[2] Riemer, F., McHugh, D., Zaccagna, F., Lewis, D., McLean, M.A., Graves, M.J., Gilbert, F.J., Parker, G.J.M., Gallagher, F.A., 2019. Measuring tissue sodium concentration: Cross‐vendor repeatability and reproducibility of 23 Na‐MRI across two sites. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 50, 1278–1284. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.26705

[3] Harrington, M.G., Salomon, R.M., Pogoda, J.M., Oborina, E., Okey, N., Johnson, B., Schmidt, D., Fonteh, A.N., Dalleska, N.F., 2010. Cerebrospinal fluid sodium rhythms. Fluids Barriers CNS 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8454-7-3

[4] Nowikow, C.E., Polak, P., Noseworthy, M.D., 2022. Variability in Brain Sodium TSC Mapping Quantification Methods. In: Proc. 2022 ISMRM and ESMRMB Joint Conference London, UK.

[5] Coste, A., Boumezbeur, F., Vignaud, A., Madelin, G., Reetz, K., Le Bihan, D., Rabrait-Lerman, C., Romanzetti, S., 2019. Tissue sodium concentration and sodium T1 mapping of the human brain at 3 T using a Variable Flip Angle method. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 58, 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2019.01.015

[6] Jenkinson, M., Bannister, P., Brady, J. M., & Smith, S. M., 2002. Improved Optimisation for the Robust and Accurate Linear Registration and Motion Correction of Brain Images. NeuroImage, 17(2), 825-841.

[7] Jenkinson, M., Beckmann, C.F., Behrens, T.E., Woolrich, M.W., Smith, S.M., 2012. FSL. NeuroImage, 62:782-90

[8] R Core Team, 2022. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL: https://www.R-project.org/.

[9] Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., Walker, S., 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1-48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01Figures

Figure 1: (A) A raw 70° flip angle sodium image and (B) its respective TSC map.

Figure 2: The average sodium concentration across all 10 ROIs per subject as separated into each time-of-day.

Figure 3: The sodium concentrations of each ROI for subjects 1 (A) and 7 (B) as separated into the three times of day.

Table 1: The results of the ANOVA analysis on the TSC brain region data. The column titles are sum of squares (Sum Sq.), degrees of freedom (d.f.), mean square (Mean Sq.), F-distribution value (F). The acronyms for the sources are region-of-interest (ROI), time-of-day (TOD), signal-to-noise (SNR), and linewidth (LB).