1252

Evaluation of the brain volumes development of fetuses with isolated non-severe ventriculomegaly using MRI1Department of Radiology, Guangzhou Women and Children's Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University,Guangdong Provincial Clinical Research Center for Child Health, Guangzhou, 510623, China, Guangzhou of China, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Prenatal, Brain

The objective of our study to perform the development of brain volume in fetus with the isolated non-severe ventriculomegaly (INSVM). Then the MRI images of 36 INSVM fetuses and 22 normal fetuses were retrospectively collected, and were manually delineated to obtain quantitative data of brain regions. The gestational age ranged from 26 to 35 weeks. Our study found that the volume development of the basal ganglia, thalamus, and partial white matter in the INSVM fetuses were different from those in the normal fetuses. These differences in the volume development of brain regions need to be determined by expanding the sample.Introduction

Isolated non-severe ventriculomegaly (INSVM) is the most common prenatal manifestation of intracranial structural abnormalities1. The prognoses of INSVM fetuses are uncertain and there exists the risk of neurobehavioral delay in INSVM fetuses2. However, previous researches on the developments of each structure of the fetal brain in INSVM are still unclear, and existed some bifurcations. The objective of this study was to investigate the brain volumes development of INSVM using MRI and explore whether there are any differences in brain development between INSVM fetuses and normal fetuses.Methods

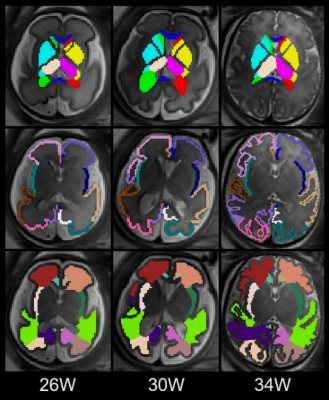

The MRI images of 36 fetuses in the INSVM group and 22 fetuses in the control group were retrospectively collected and were manually delineated using ITK-snap 3.8 software3. INSVM was defined as the width of the lateral ventricle between 10.0 and 14.9 mm, without other brain structural abnormalities detected by imaging. All fetuses with chromosomal and genetic abnormalities, infections, other structural abnormalities, and a high risk of neurodevelopmental abnormalities were excluded. The gestational age (GA) ranged from 26 to 35 weeks (W). The left and right cerebral hemispheres were divided into 30 regions4 (lateral ventricle, basal ganglia, thalamus, and the gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) of frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, occipital lobe, insular lobe, and cingulate gyrus) (Figure 1), and the quantitative data of brain volumes in each region with the change of gestational age were obtained. Finally, all statistical analyzes were conducted with SPSS 26.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.Results

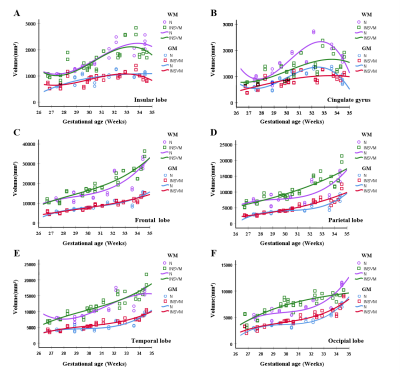

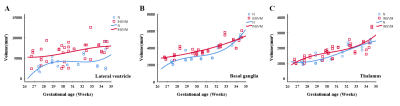

With the increase of GA, the development curves of WM volumes in cingulate, parietal and occipital lobes in INSVM group were different from those in normal group (Figure 2). At 28-34W GA, the parietal and occipital WM volumes in INSVM group were significantly larger than those in the control group (p < 0.01), and the cingulate WM volumes in INSVM group were significantly smaller than those in the control group (p = 0.045). The development curves of GM volumes in all regions, and WM volumes in frontal, temporal and insular lobes were similar between the two groups (p > 0.05) (Figure 2). The development curves of volumes in lateral ventricle, basal ganglia and thalamus in INSVM group were different from those in normal group (Figure 3). The volumes of lateral ventricle was significantly larger than the normal group (p < 0.01). The volumes of basal ganglia before 34W GA was significantly larger than the normal group (p = 0.01), and the volumes of thalamus before 33W GA was significantly larger than the normal group (p = 0.04).Discussion

In this study, the volumes growth curves of each brain region in INSVM fetuses were explored and were compared with those in normal fetuses. Our results showed that the development curves of WM volumes in cingulate gyrus, parietal and occipital lobes in INSVM group were different from those in the normal group. The parietal and occipital lobe and part of the cingulate gyrus are located in the posterior horn of the lateral ventricle, and the posterior horn is usually dilated with the presence of ventriculomegaly. Therefore, these structures are more likely to be affected by ventriculomegaly. For one thing, the increased volumes of parietal and occipital WM in the INSVM group may result from the increased number or decreased apoptosis of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in the germinal matrix of the lateral ventricular wall with ventriculomegaly5-7. For another, in contrast to the parietal and occipital WM volumes results, the cingulate gyrus WM volumes reduced in the INSVM group. The presence of opposite changes in adjacent brain regions may reflect changes in interactions between different brain regions with ventriculomegaly8. Meanwhile, the development curves of basal ganglia and thalamus volumes in the INSVM group was different from those in the normal group. Indeed, the ganglionic eminences, which are located in the lateral walls9, are closely related to the basal ganglia and thalamus development. In the presence of ventriculomegaly, we speculate that the ganglionic eminences generates more neurons, leading to an increase in the basal ganglia and thalamus volumes. And the degeneration of the ganglionic eminences occurred at 34-36W GA10,11, which explained that the basal ganglia and thalamus volumes in the INSVM group were significantly larger than those in the normal group before 33W GA. In addition, our results are consistent with previous data showing similarities in cortical development12, but some studies have shown that the GM volumes of INSVM fetuses are significantly higher than those of normal fetuses8,13. The different results of GM volumes can be explained by the different methods of brain regions segmentation and the limitation of sample size in our study. In the future, we will expand the sample size, and conduct multicenter trials if possible.Conclusion

There are differences in the development of different brain regions in fetuses with INSVM, which may be a potential prognostic biomarker for further large-scale studies to clarify the growth and development of fetuses with INSVM, identify high-risk cases, and determine the subtle changes in brain development of fetuses with INSVM.Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou (202201020630, 202201020627).References

Figures