1251

Automated atlas-based craniofacial biometry for 3D fetal MRI: multi-acquisition comparison of fetuses with Down syndrome and a control cohort.1Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2City University London, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Prenatal, Fetus, Biometry

We introduce the first automated atlas-based method for fetal craniofacial biometry. Using motion-corrected slice-to-volume reconstructions for 3D fetal head visualisation, an automated label propagation method extracted linear biometry across 12 measures. The optimisation process used retrospective data and no differences in automated biometry was seen between different MRI acquisition parameters. A comparison of measures made between a cohort of fetuses with Down syndrome and control fetuses, with normal development, found significant differences for the occipitofrontal skull, oral hard palate and anterior base of skull distances. This suggests a promising and meaningful method for large population-level investigation of MRI craniofacial morphology.Introduction

Comprehensive prenatal characterisation of craniofacial development remains a challenge for obstetric ultrasound due to limitations caused by fetal position, artefacts, and technical difficulties in the 2D and 3D domain1. T2w-ssTSE fetal MRI provides superior visualisation of fetal craniofacial features2,3 and yet 2D slice-wise biometry is often limited due to the off-plane axis of anatomy and random fetal movement. Yet, in the setting of fetal brain imaging, craniofacial structures are usually only qualitatively assessed despite the important link between craniofacial structural changes and more than 250 genetic and chromosomal syndromes that may have a neurodevelopmental impact4,5.Slice-to-volume registration (SVR) motion correction tools6 allow reconstruction of high-resolution 3D isotropic images of the fetal head and overcomes some of the limitations of 2D fetal MRI. SVR restores 3D information for visualisation7 and images can be reoriented to provide reliable planes for fetal skull biometry, which is beneficial because manual biometry is time-consuming and affected by intra- and inter-observer bias8,9. Recently, there has been a focus on deep learning and label propagation for automation of the fetal cranial vault and ocular measurements10–12. However, to comprehensively assess fetal craniofacial development at population-level, a wider range of biometrics is required13.

In this work, we present the first protocol for an automated set of 12 craniofacial distance measurements using 3D SVR and atlas-based label propagation of MRI-defined anatomical landmarks. The utility of the proposed approach is assessed by comparison of normative growth charts from control datasets with heterogenous acquisition parameters and a cohort of fetuses with confirmed Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome, DS), the most common chromosomal anomaly with an incidence of 1 in 700 live births.

Method

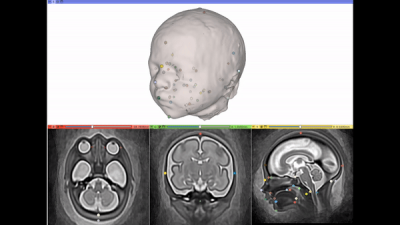

MRI Datasets and preprocessing: We included 24 fetuses with genetically confirmed DS, and 85 typically developing control fetuses (Fig.1A) scanned between 2014 and 2020 at a single site, St Thomas’ Hospital, London. All maternal participants gave written informed consent for either: The ‘Quantification of fetal growth and development using MRI study’ [REC: 07/H0707/105]; eBIDS [REC: 19/LO/0667]; dHCP [REC: 14/LO/1169]; PiP [REC: 16/LO/1573]; or iFIND [REC: 14/LO/1806].Controls were matched to the different acquisition protocols seen in the DS cohort (Fig. 1A). All datasets were reconstructed to 3D isotropic images of the head ROI with 0.5 or 0.75mm resolution using automated SVR methods14–16. The inclusion criteria were high SNR characterised by good differentiation between brain and cranial structures and clear tissue texture, 29-37 weeks gestational age (GA) and acceptable reconstruction quality (visibility of all head structures).

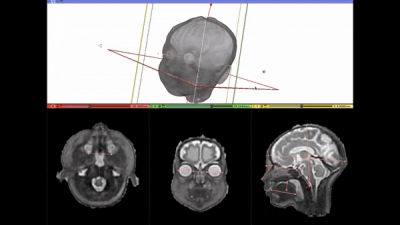

Definition of craniofacial landmark protocol: Similar to our previously reported spatiotemporal fetal head dHCP atlas11 (3T/TE=250ms), we generated an additional atlas from 15 control datasets (29-32 weeks GA, 1.5T/TE=80ms) using the MIRTK atlas tool17,18. The prenatal craniofacial MRI literature19,20; ex-vivo post-mortem fetal, paediatric, and adult anatomical studies21–23; and prenatal ultrasound and CT literature24,25 were reviewed by a clinician trained in fetal MRI and ultrasound (JM) and 46 fetal MRI-reliable craniofacial landmarks for biometry were labelled in the atlas using ITK-SNAP (fig.2-3)26.

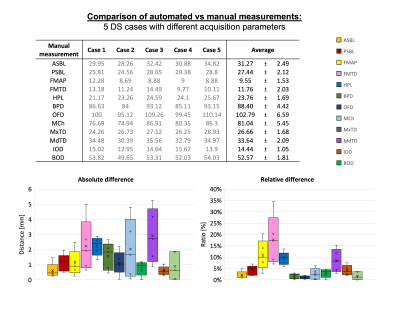

Automated biometry: The pipeline for automated biometry (Fig.1B) is based on atlas label propagation (using nonrigid MIRTK registration: FFD with LNCC metric and 6 mm kernel size)27 followed by the calculation of the distances between selected landmark centre-points. The performance was tested on 5 DS datasets by comparing manual measurements using MITK workbench28 to the automated distances. Lastly, we investigated the feasibility of this approach by comparing the automated DS biometry results to the control groups and assessed different acquisition protocols.

Results and Discussion

Craniofacial landmark protocol: The anatomical accuracy of the propagated landmarks was visually compared to the defined atlas-based landmarks in; 1. the control group (AU) and, 2. the DS cohort (JM). No landmarks in the control group required modification however, in the DS group, 4 out of 120 automated landmarks required minor manual adjustment.Automated biometry: The automatically derived distances compared to the manual measurements showed small mean paired relative errors of <10% except for foramen magnum measurements (fig.4), and reliability studies are required for further evaluation29. The differences were primarily caused by variability in manual adjustment of the planes and suboptimal regional visibility of finer features. The process of verifying the correct positioning of landmarks was also significantly faster than extracting manual biometry (5 vs 25 minutes/case).

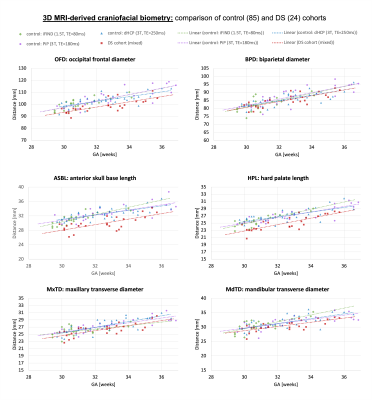

Comparison of groups: There is no significant difference between the control cohorts studied with different acquisition parameters (1.5T, 3T; TE=80ms, TE=180ms, TE=250ms), which confirms the feasibility of using the landmark propagation approach for different image contrasts (fig.5). An ANOVA comparison of biometrics between the normal and DS cohorts revealed significant differences in OFD, ASBL and HPL distances (p<0.001). These differences are likely associated with shorter wider skulls (brachycephaly) and smaller mid-facies (mid-face hypoplasia) consistent ultrasound and postmortem findings in DS cohorts5,19,30.

Conclusions

This work introduced an evaluation of the first automated solution for 3D fetal MRI craniofacial biometry with atlas-defined landmarks and label propagation. We also investigated the practical application of the pipeline for comparison of the DS and normal control cohorts with different MRI acquisition parameters. Further work will include validation and optimisation of the landmark propagation pipeline for a wider GA range, with the potential for large-scale quantitative deep craniofacial phenotyping in high-risk fetuses.Acknowledgements

JM and AU contributed equally in the preparation of the abstract.

We thank everyone who was involved in the acquisition and analysis of the datasets at the Department of Perinatal Imaging and Health at King’s College London. We thank all participating mothers and families.

This work was supported by: The European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme ([FP7/ 20072013]/ERC grant agreement no. 319456) for the dHCP project; the Wellcome Trust and EPSRC IEH award [102431] for the iFIND project and the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering at King’s College London [WT 203148/Z/16/Z]; the NIH (Human Placenta Project [grant 1U01HD087202-01]) for the PIP study; the Medical Research Council ([MR/K006355/1] and [MR/LO11530/1]), Rosetrees Trust [A1563], Fondation Jérôme Lejeune [2017b–1707], and Sparks and Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity [V5318] for eBIDs; and the NIHR Clinical Research Facility at Guy’s and St Thomas’ and by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. JM was supported by an NIHR clinical doctoral research fellowship (NIHR300555).

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

References

[1] Mak ASL, Leung KY. Prenatal ultrasonography of craniofacial abnormalities. Ultrasonography. 2019. DOI: 10.14366/usg.18031.

[2] Arangio P, Manganaro L, Pacifici A, et al. Importance of fetal MRI in evaluation of craniofacial deformities. J Craniofac Surg 2013; 24: 773–776.

[3] Nagarajan M, Sharbidre KG, Bhabad SH, et al. MR Imaging of the Fetal Face: Comprehensive Review. Radiographics. Epub ahead of print 2018. DOI: 10.1148/rg.2018170142.

[4] Mossey, P. Castilla E (Eds). Global registry and database on craniofacial anomalies Report of a WHO Registry Meeting on Craniofacial Anomalies Human Genetics Programme Management of Noncommunicable Diseases World Health Organization Geneva, Switzerland WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publ, https://www.who.int/genomics/anomalies/en/CFA-RegistryMeeting-2001.pdf (2003, accessed 29 December 2020).

[5] Ettema AM, Wenghoefer M, Hansmann M, et al. Prenatal Diagnosis of Craniomaxillofacial Malformations: A Characterization of Phenotypes in Trisomies 13, 18, and 21 by Ultrasound and Pathology. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J 2010; 47: 189–196.

[6] Uus AU, Egloff Collado A, Roberts TA, et al. Retrospective motion correction in foetal MRI for clinical applications: existing methods, applications and integration into clinical practice. Br J Radiol. Epub ahead of print 8 August 2022. DOI: 10.1259/BJR.20220071.

[7] Matthew J, Deprez M, Uus A, et al. OC11.08: Syndromic craniofacial dysmorphic feature assessment in utero: potential for a novel imaging methodology with reconstructed 3D fetal MRI models. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019; 54: 29–29.

[8] Kyriakopoulou V, Vatansever D, Davidson A, et al. Normative biometry of the fetal brain using magnetic resonance imaging. Brain Struct Funct 2017; 222: 2295–2307.

[9] Khawam M, de Dumast P, Deman P, et al. Fetal Brain Biometric Measurements on 3D Super-Resolution Reconstructed T2-Weighted MRI: An Intra- and Inter-observer Agreement Study. Front Pediatr 2021; 0: 651.

[10] Avisdris N, Yehuda B, Ben-Zvi O, et al. Automatic linear measurements of the fetal brain on MRI with deep neural networks. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg 2021; 16: 1481–1492.

[11] Uus A, Matthew J, Grigorescu I, et al. Spatio-Temporal Atlas of Normal Fetal Craniofacial Feature Development and CNN-Based Ocular Biometry for Motion-Corrected Fetal MRI. Lect Notes Comput Sci (including Subser Lect Notes Artif Intell Lect Notes Bioinformatics) 2021; 12959 LNCS: 168–178.

[12] Velasco-Annis C, Gholipour A, Afacan O, et al. Normative biometrics for fetal ocular growth using volumetric MRI reconstruction. Prenat Diagn 2015; 35: 400–408.

[13] Toren A, Spevac S, Hoffman C, et al. What does the normal fetal face look like? MR imaging of the developing mandible and nasal cavity. Eur J Radiol 2020; 126: 108937.

[14] Kuklisova-Murgasova M, Quaghebeur G, Rutherford MA, et al. Reconstruction of fetal brain MRI with intensity matching and complete outlier removal. Med Image Anal 2012; 16: 1550.

[15] SVRTK: MIRTK based SVR package for fetal MRI, https://github.com/SVRTK/ (accessed 9 November 2022).

[16] Cordero-Grande L, Price AN, Hughes EJ, et al. Automating fetal brain reconstruction using distance regression learning. In: ISMRM 27th Annual Meeting and Exhibition, https://archive.ismrm.org/2019/4779.html (2019, accessed 14 September 2021).

[17] MIRTK package, https://github.com/BioMedIA/MIRTK/ (accessed 9 November 2022).

[18] Schuh A, Murgasova M, Makropoulos A, et al. Construction of a 4D brain atlas and growth model using diffeomorphic registration. Lect Notes Comput Sci (including Subser Lect Notes Artif Intell Lect Notes Bioinformatics) 2015; 8682: 27–37.

[19] Vicente A, Bravo-González LA, López-Romero A, et al. Craniofacial morphology in down syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Reports 2020 101 2020; 10: 1–14.

[20] Begnoni G, Serrao G, Serrao G, et al. Craniofacial structures’ development in prenatal period : An MRI study. Orthod Craniofac Res. Epub ahead of print 2018. DOI: 10.1111/ocr.12222.

[21] Jeffery N. A high-resolution MRI study of linear growth of the human fetal skull base. Neuroradiology 2002; 44: 358–366.

[22] Jeffery N. Cranial base angulation and growth of the human fetal pharynx. Anat Rec - Part A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 2005; 284: 491–499.

[23] Grzonkowska M, Baumgart M, Badura M, et al. Quantitative anatomy of primary ossification centres of the lateral and basilar parts of the occipital bone in the human foetus. Folia Morphol 2021; 80: 895–903.

[24] Garel C, Vande Perre S, Guilbaud L, et al. Contribution of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in the analysis of fetal craniofacial malformations. Pediatr Radiol 2021; 51: 1917–1928.

[25] Perry JL, Kollara L, Kuehn DP, et al. Examining age, sex, and race characteristics of velopharyngeal structures in 4- to 9-year old children using magnetic resonance imaging. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2018; 55: 21–34.

[26] ITK-SNAP tool, http://www.itksnap.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php (accessed 9 November 2022).

[27] Rueckert D, Sonoda LI, Hayes C, et al. Nonrigid registration using free-form deformations: Application to breast mr images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 1999; 18: 712–721.

[28] The Medical Imaging Interaction Toolkit (MITK), https://www.mitk.org/wiki/The_Medical_Imaging_Interaction_Toolkit_(MITK) (accessed 9 November 2022).

[29] Coelho Neto MA, Roncato P, Nastri CO, et al. True Reproducibility of UltraSound Techniques (TRUST): Systematic review of reliability studies in obstetrics and gynecology. Ultrasound Obs Gynecol 2015; 46: 14–20.

[30] Guihard-Costa, AM., Khung, S., Delbecque, K. et al. Biometry of Face and Brain in Fetuses with Trisomy 21. Pediatr Res 59, 33–38 (2006).

Figures

Fig.1 (A) Summary description of the fetal MRI datasets investigated in this study. (B) Proposed pipeline for automated craniofacial biometry for 3D fetal head MRI based on atlas landmark propagation.

Fig.5: Comparison of biometric measurements from 29 to 37 weeks GA: DS compared to typically developing control fetuses from MRI studies with different acquisition protocols.