1248

Development of the fetal brain structural connectivity during the second-to-third trimester based on diffusion MRI1Key Laboratory for Biomedical Engineering of Ministry of Education, Department of Biomedical Engineering, College of Biomedical Engineering & Instrument Science, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2Department of Radiology, Beijing Hospital, National Center of Gerontology, Institute of Geriatric Medicine, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, P.R. China., Beijing, China, 3Department of Radiology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, Shandong, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Fetal, Brain Connectivity, Structural Connectivity Network

Extensive cortico-cortical connections emerge in the fetal brain during the second-to-third trimester with the rapid development of white matter fiber pathways. However, the early establishment and prenatal development of the brain’s structural network are not yet understood. In this work, we built structural connectivity networks of the fetal brain using in-utero diffusion MRI data. Network analysis revealed the increasing overall efficiency of the fetal brain network. The strengthening of short-ranged cortico-cortical connections and the emerging hubs contributed to the reorganization of its sub-units. These findings provided valuable information on the early developmental patterns of brain cortico-cortical structural connectivityIntroduction

Neuronal pathways of the fetal brain develop rapidly during the second-to-third trimester, forming early cortico-cortical structural connections 1. There have been a few studies on the development of structural connectivity networks (SCN) during this period based on post-mortem fetuses or preterm neonates, which reported growing network strength and increasing efficiency 2-4. Some studies also observed adult-like properties such as small-worldness and rich-club organizations in the developing brains 3,5. However, few studies have investigated the development of cortico-cortical connectivity networks in-utero due to the lack of data. In this work, we aim to use in-utero diffusion MRI (dMRI) data to build the SCN of the fetal brain from the second-to-third trimester and to decipher its developmental patterns.Methods

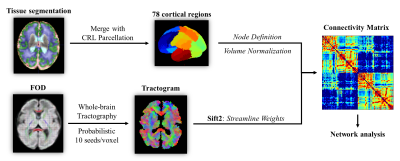

A total of 161 fetuses were scanned in-utero at gestational age (GA) from 25 to 38 weeks (W) on a 3T Siemens scanner using a dMRI sequence with b = 600 s/mm², 30 gradient directions, 8 non-diffusion-weighted images, 1.73 mm in-plane resolution, 4 mm slice thickness, and two averages. 114 scans remained after excluding those with large motion, noise, or other abnormalities.Raw data were preprocessed in MRtrix3, allowing denoising, eddy-current distortion correction, between-volume motion correction, and bias removal 6. Images were slice-to-volume-registered and reconstructed to 1.2 mm isotropic resolution using SVRTK 7. We estimated each subject’s fiber orientation distribution (FOD) for probabilistic tractography 8,9. Spherical-deconvolution Informed Filtering of Tractograms was performed to reweight streamlines according to the underlying FOD 10. Seventy-eight cortical regions of interest (ROIs) were obtained by merging the CRL fetal brain parcellations 11 with the cortical tissue label of our previously published fetal brain atlas 12 and transformed to subject spaces, defining the nodes of SCN. The edges were calculated by the sum of streamline weights between every two nodes, normalized by nodal volumes (Figure 1).Global efficiency (Eglob), local efficiency (Eloc), shortest path length (Lp), weighted nodal degree, and nodal betweenness of each subject network were calculated in MATLAB using the GRETNA 2.0 toolbox (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/gretna/). The clustering coefficient (CC) was calculated by an algorithm suitable for weighted connectomes 13. Small-worldness was measured by SW=CCnorm/Lpnorm, where CCnorm and Lpnorm are the CC and Lp normalized by the mean CC and Lp of the network’s 100 degree-matched random networks. We then performed Pearson’s correlation analysis between network properties and GA, as well as between each edge’s strength and GA. Correlations with FDR-corrected p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

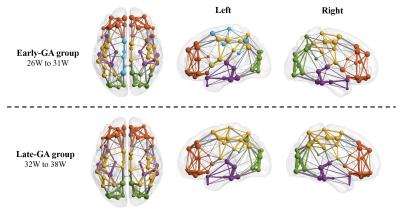

To compare the characteristics of fetal brain SCN during different developmental periods, we separated scans before and after 31W into the early-GA and the late-GA groups, containing 53 and 61 subjects respectively. Louvain community detection algorithm was used to identify modular structures in each group-wise network 14. Nodal degree and betweenness were averaged across subjects in each group. Nodes whose degree or betweenness centrality higher than the mean + standard deviation of all nodes were defined as hubs.

Results

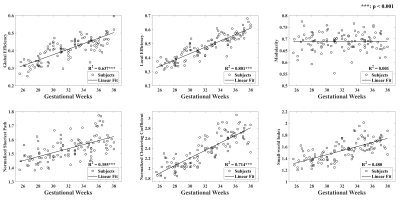

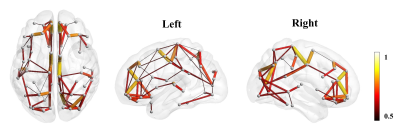

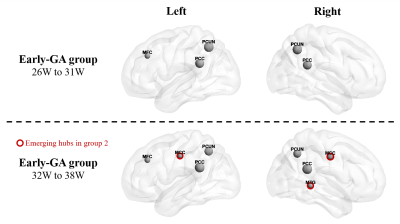

The Eglob and Eloc of the fetal brain SCN increased significantly over GA. CCnorm and Lpnorm both increased significantly, with CCnorm having a higher growth rate, resulting in increasing SW. Modularity was steady over the studied period (Figure 2). The edge strength increased heterogeneously across regions. Short-ranged connectivity in the frontal and occipital lobes and those connecting the limbic nodes with their neighboring regions developed most significantly (Figure 3).Different network patterns were observed in the early-GA and late-GA groups. Networks were generally divided into 4 to 5 modules each hemisphere, in which the frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal modules were relatively consistent between the two groups. The limbic module was only detected in the left hemisphere of the early-GA group, which merged with the parietal and occipital modules later (Figure 4). In both groups, the bilateral precuneus, posterior cingulate cortex, and left middle frontal cortex were identified as hubs. The bilateral middle cingulate cortex and right middle temporal gyrus were identified only in the late-GA group (Figure 5).

Discussion

The observed development of fetal brain SCN suggested complicated reorganization during the second-to-third trimester. On the whole-brain level, the significant increases in Eglob and Eloc reflected simultaneous integration and segregation of fetal brain SCN. The increasing Lpnorm also showed segregation of nodes, indicating some of the nodes became more remotely connected. On the other hand, CCnorm and SW increased significantly, indicating the improved performance of the network with reduced wiring cost 15.Network edge strength developed heterogeneously across regions, with short-ranged connections strengthened most prominently. This observation coincided with the emergence of short-ranged cortico-cortical fiber pathways during the second-to-third trimester 16. The frontal and occipital modules were stabilized regardless of the change in edge strength, while the strengthened limbic-to-parietal connections may have caused the reorganization of the left limbic module.

A higher number of hubs were observed in the late-GA group compared to the early-GA group. The emergence of additional hubs may explain the increase of Lpnorm by becoming common connectors of other nodes to maintain small-worldness.

Conclusion

We studied the development of the in-utero fetal brain structural network, which displayed both integration and segregation patterns during the second-to-third trimester. The strengthening of short-ranged cortico-cortical connections and the emerging hubs contributed to the reorganization of the network.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (2018YFE0114600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61801424, 81971606, 82122032, 2021ZD0200202), and the Science and Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (202006140, 2022C03057).References

1. Takahashi E, Hayashi E, Schmahmann J D, et al. Development of cerebellar connectivity in human fetal brains revealed by high angular resolution diffusion tractography. Neuroimage. 2014;96:326-333.

2. Brown C J, Miller S P, Booth B G, et al. Structural network analysis of brain development in young preterm neonates. Neuroimage. 2014;101:667-680.

3. Song L, Mishra V, Ouyang M, et al. Human Fetal Brain Connectome: Structural Network Development from Middle Fetal Stage to Birth. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2017;11:561.

4. Zhao T, Mishra V, Jeon T, et al. Structural network maturation of the preterm human brain. Neuroimage. 2019;185:699-710.

5. Ball G, Aljabar P, Zebari S, et al. Rich-club organization of the newborn human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111 (20):7456-7461.

6. Tournier J D, Smith R, Raffelt D, et al. MRtrix3: A fast, flexible and open software framework for medical image processing and visualisation. Neuroimage. 2019;202:116137.

7. Deprez M, Price A, Christiaens D, et al. Higher Order Spherical Harmonics Reconstruction of Fetal Diffusion MRI With Intensity Correction. Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2020;39 (4):1104-1113.

8. Tournier J D, Calamante F and Connelly A. Robust determination of the fibre orientation distribution in diffusion MRI: Non-negativity constrained super-resolved spherical deconvolution. Neuroimage. 2007;35 (4):1459-1472.

9. Tournier J D C, Fernando; Connelly, Alan. Improved probabilistic streamlines tractography by 2nd order integration over fibre orientation distributions. Proceedings of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2010;1670.

10. Smith R E, Tournier J-D, Calamante F, et al. SIFT2: Enabling dense quantitative assessment of brain white matter connectivity using streamlines tractography. Neuroimage. 2015;119:338-351.

11. Gholipour A, Limperopoulos C, Clancy S, et al. Construction of a Deformable Spatiotemporal MRI Atlas of the Fetal Brain: Evaluation of Similarity Metrics and Deformation Models. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention - Miccai 2014, Pt Ii. 2014.

12. Xu X, Sun C, Sun J, et al. Spatiotemporal atlas of the fetal brain depicts cortical developmental gradient in Chinese population. bioRxiv. 2022.

13. Zhang B and Horvath S. A general framework for weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Statistical applications in genetics and molecular biology. 2005;4 (1):1-45.

14. Blondel V D, Guillaume J-L, Lambiotte R, et al. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics-Theory and Experiment. 2008.

15. Latora V and Marchiori M. Efficient behavior of small-world networks. Physical Review Letters. 2001;87 (19):198701.

16. Takahashi E, Folkerth R D, Galaburda A M, et al. Emerging Cerebral Connectivity in the Human Fetal Brain: An MR Tractography Study. Cerebral Cortex. 2012;22 (2):455-464.

Figures

Figure 1: The pipeline for building the fetal brain structural connectivity network. Seventy-eight nodes were defined by merging the cortical label of our previously published fetal brain atlas and the tissue parcellation provided by the CRL atlas. The edge between every two nodes was calculated by the sum of the weights for all streamlines connecting the nodes, normalized by the volumes of ROIs.

Figure 2: Network properties of the fetal brain structural connectivity network during 25 to 38 weeks of gestation. Global and local efficiency, normalized shortest path length, normalized clustering coefficient, and small-worldness increased significantly (FDR-corrected p-values < 0.001), while modularity remained unchanged.

Figure 5: Hub nodes of fetal brain SCN. Bilateral precuneus cortex (PCUN) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), and left middle frontal cortex (MFC) were detected as hub nodes in both groups. Bilateral middle cingulate cortex (MCC) and right middle temporal gyrus (MTG) hubs were only observed in group 2.