1244

Multiresolution comparison of fetal CINE MRI at 0.55 T1Translational Medicine, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Ming Hsieh Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Viterbi School of Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 3Biomedical Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 4Division of Cardiology, Department of Pediatrics and Radiology, Children's Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 5Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Prenatal, Fetus

In this study, we demonstrate the feasibility of CINE fetal CMR at 0.55 T at multiple spatial resolutions. First, real-time images are reconstructed for motion-correction and cardiac gating. Fetal cardiac CINEs are then reconstructed using the corrected data. Retrospective CINEs have higher SNR relative to their corresponding real-time reconstructions. Feasibility of the pipeline is demonstrated for up to 1.0 mm in-plane resolution. Good cardiac structure conspicuity is observed at coarse spatial resolutions in real-times and at all spatial resolutions in CINEs.Introduction

Fetal cardiovascular MRI (CMR) faces several challenges such as small cardiac structures, high heart rates and uncontrollable motion [1], [2]. Dynamic imaging in the form of real-time images or cardiac-gated CINEs allow for visualizing moving structures to aid pathology assessment.Recently developed lower field, wider bore MRI systems (0.55 T, 70 cm) have potential for providing a more comfortable and accessible platform for fetal CMR. The goal of this work is to demonstrate and compare real-time and CINE reconstructions of spiral SSFP of the human fetal heart at 0.55 T. Real-time reconstructions allow for dynamic visualization of cardiac function and anatomy but are limited by low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) at high spatiotemporal resolutions. On the other hand, CINE reconstructions combine data acquired over many heart beats to yield dynamic visualization with high SNR but are limited by motion corruption and the need for a cardiac gating signal. Here, we apply motion-correction with a CINE reconstruction framework for fetal spiral SSFP, previously developed for radial imaging at 1.5 T [3], and demonstrate its utility for fetal CMR at high spatiotemporal resolution with spiral imaging at 0.55 T.

Methods

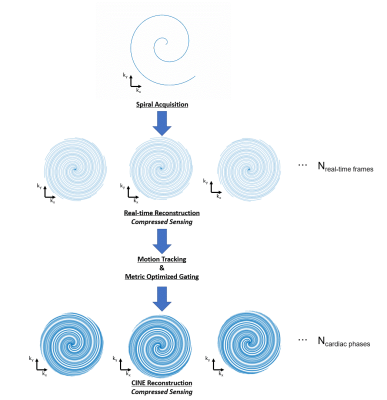

Four human pregnancies (Fetus 1-4, gestational age 32-34 weeks) were imaged under free breathing conditions using a whole-body 0.55 T scanner (prototype Magnetom Aera, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with high-performance shielded gradients (45 mT/m amplitude, 200 T/m/s slew rate). Acquisitions were performed with the following parameters: field-of-view = 240×240 mm2, slice thickness = 4 mm, spatial resolutions = 1.0×1.0 mm2, 1.5×1.5 mm2, and 1.7×1.7 mm2, spiral arms = 2600–3500, interleaves = 63, echo time = 0.9 ms, repetition time = 5.7 ms, flip angle = 90o, and trajectory = pseudo golden angle (repeated after every 144 arms).As shown in Figure 1, real-time reconstructions were performed with compressed sensing (CS, temporal finite difference: 0.08) using 15 arms with 10 arms shared between frames (interpolated temporal resolution of ~29 ms) using framework from [4]. Translational motion correction and data rejection from through-plane motion were performed on the real-time reconstructions. Motion-corrected real-times were then used to derive the fetal heart rate using metric optimized gating (MOG) [5]. The gated motion-corrected k-space was then reconstructed into a CINE (20 cardiac phases, temporal resolution ~22ms) using CS (temporal finite difference: 0.02). Real-time and CINE reconstructions were compared for image quality using SNR.

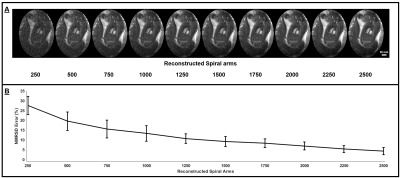

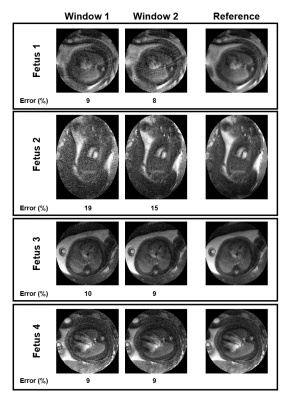

To assess the effect of acceleration on CINE image quality, the 1.0 mm resolution data was also reconstructed into CINEs using increasing number of arms (250 to 2500 at increments of 250, where 250 arms corresponded to 1.425 s). Normalized root-mean-squared difference (NRMSD) was quantified, using a CINE reconstruction from all available data as reference [3]. Finally, to assess reproducibility of the measurement, the data was divided into 2 windows of 1250 independent arms and the NRMSD between each reconstruction and the previous reference was computed.

Results and Discussion

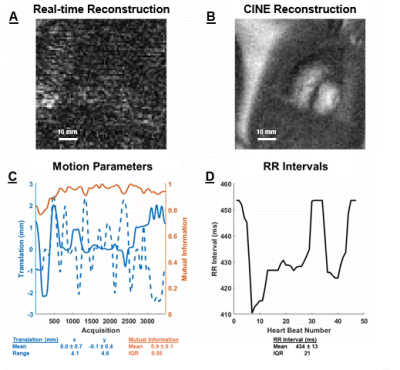

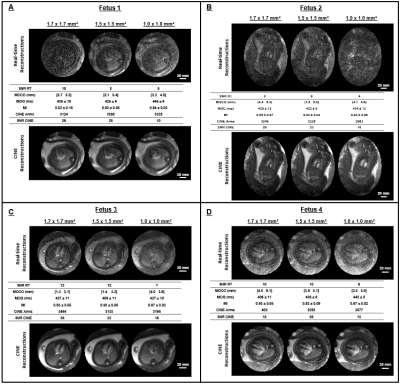

Figure 2 shows representative real-time and CINE reconstructions in Fetus 2 along with a summary of motion parameters (translation range: [4.1 4.6] mm, mutual information: 0.9 ± 0.1) and fetal RR interval (434 ± 13 ms) derived from the real-time images. Figure 3 compares real-time and CINE images, reconstructed from the same acquisitions, from each fetus. For real-time reconstructions, the measured SNRs across all fetuses were 10 ± 1, 9 ± 3 and 6 ± 1 for resolutions of 1.7 mm, 1.5 mm, and 1.0 mm, respectively. At increasing spatial resolution, real-times degraded with cardiac details becoming less conspicuous with decreasing SNR. The lower SNR in 1.0 mm real-times still allowed for motion correction and MOG. Similarly, CINE SNR measurements decreased with increasing spatial resolution (28 ± 9, 27 ± 4 and 12 ± 3, respectively) as expected. At each resolution, CINE reconstructions had better SNR (3 ± 1 times) than their corresponding real-times, with CINE at 1.0 mm still providing better SNR than real-times at 1.7 mm. Since CINE reconstructions combine more data into each image frame, they provide higher SNR and improve conspicuity of cardiac structures, particularly at high resolution.Figure 4 shows the effect of undersampling on CINE image quality, with NRMSD error decreasing monotonically with increasing number of arms. Errors in the undersampled data sprout from 3 sources: (1) increased noise and undersampling artifacts, (2) variation in data rejection in motion correction, and (3) variation of spiral arm clustering at different segments of the fetal heart rates. Assuming an acceptable NRMSD value is 10 %, CINE reconstructions can be achieved with as few as 1250 arms.

Figure 5 depicts the reproducibility of CINE reconstruction. The average NRMSD across all fetuses was 11 ± 4 %, showing good consistency between the reconstructions of independent data. Note the first window in Fetus 2 had the highest error (19 %) owing to signal not having reached steady state in that period, leading to residual artifact.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated the feasibility of fetal CINE SSFP CMR at 0.55 T. Real-times showed good visualization but can be limited by SNR at the highest spatiotemporal resolutions. Motion corrected CINEs were of high quality at resolutions up to 1.0 mm spatial and 20 ms temporal.Acknowledgements

Christopher Macgowan and Krishna Nayak have joint senior authorship.

This work was supported by USC Provost’s Strategic Direction for Research Award and KSOM Dean’s Pilot Grant.

References

[1] C. Firpo, J. I. Hoffman, and N. H. Silverman, “Evaluation of fetal heart dimensions from 12 weeks to term,” Am J Cardiol, vol. 87, no. 5, pp. 594–600, Mar. 2001.

[2] T. Wheeler and A. Murrills, “Patterns of fetal heart rate during normal pregnancy,” Br J Obstet Gynaecol, vol. 85, no. 1, pp. 18–27, Jan. 1978.

[3] C. W. Roy, M. Seed, J. C. Kingdom, and C. K. Macgowan, “Motion compensated cine CMR of the fetal heart using radial undersampling and compressed sensing,” Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 29, Mar. 2017.

[4] Y. Tian, Y. Lim, Z. Zhao, D. Byrd, S. Narayanan, and K. S. Nayak, “Aliasing Artifact Reduction in Spiral Real-Time MRI,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 86, no. 2, pp. 916–925, Aug. 2021.

[5] M. S. Jansz, M. Seed, J. F. P. van Amerom, D. Wong, L. Grosse-Wortmann, S.-J. Yoo, and C. K. Macgowan, “Metric optimized gating for fetal cardiac MRI,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 64, no. 5, pp. 1304–1314, Nov. 2010.

Figures