1241

Radiation Damping at Clinical Field Strengths: How to Analyse and Avoid it to enable quantitative MRI with Dedicated Coils1NMR group, Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig, Germany, 2Department of Physics, Leipzig University, Leipzig, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: System Imperfections: Measurement & Correction, Ex-Vivo Applications, Radiation Damping

Radiation damping (RD) is, in principial, well understood but commonly unconsidered in MRI. It results from inductive coupling of the spin system and the detection circuit, leading to nonlinearities in the Bloch equations. Previous research established that RD increases with the filling factor and quality factor of the coil and the magnetic field strength. However, little attention has been paid to a quantitative characterization. Moreover, implications for the RF pulse performance must be considered given similar timescales (milliseconds) of RD and pulse length. Our findings indicate that RD can impact typical MRI sequences and, consequently, parameters determined from their application.

Introduction

In quantitative MRI (qMRI), the accuracy and precision achieved with a particular imaging sequence or coil are of paramount importance. This is often assessed by comparing the results to those from a non-spatially resolved reference experiment (e.g., plain inversion recovery for T1 measurements). During this process, radiation damping1 (RD) may act as an unwanted pitfall when using coils with high Q-factors (Q>100). Several authors demonstrated successful RD supression by means of hardware modification2,3 or by integrating crusher gradients during evolution periods within the sequence4. Comparably little effort has been devoted to the interplay of RD and RF pulse performance. To gain a better understanding of its significance, we performed a detailed analysis of the spin-coil system parameters as well as RD-related errors in different experimental scenarios.Methods

Bloch-Maxwell-Equations: Simulations were based on augmented Bloch equations with terms accounting for the RD field5,6,7 with seven parameters describing the evolution of the spin-coil system: relaxation times T1, T2, T2* and RD rates and phase terms ζRDrx, ζRDtx, ψRDrx, ψRDtx during receive (Rx) and transmit (Tx).Sample preparation: 3D-printed spherical objects of varying diameters were filled with a 0.135mM MnCl2 solution and investigated as model systems.

MR experiments: Data were acquired at 3T (MAGNETOM Skyrafit) and 7T (MAGNETOM Terra) at room temperature. To characterize the spin-coil system, the following sequences were developed and implemented:

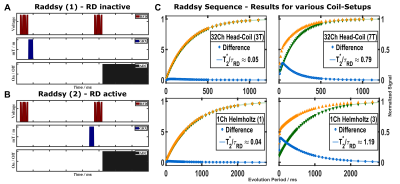

- RADDSY (RAdiation Damping Difference SpectroscopY)8 quantifies RD during Rx by comparing RD-free relaxation after 90° excitation (RADDSY-1, Figure 1A) and relaxation in the presence of RD (RADDSY-2, Figure 1B).

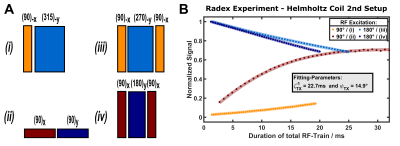

- RADDEX

(RAdiation Damping Difference EXcitation) evaluates

the performance of composite 90° and 180° pulses depending on pulse duration (Figure 2). Differences between experiments with RF pulses that are compensated for RD9 and

those that are not

reflect the RD magnitude during Tx.

Results and Discussion

Quantification of RD for both coil operating modes:Figure 1C demonstrates RD with the Helmholtz coil as accelerated, non-exponential recovery, which can be maximised by inserting an extra λ/4 cable. The effective damping rate (1/τRD) is comparable to 1/T2* (T2*/τRD≈1.19). Remarkably, a similar effect (T2*/τRD≈0.79) was produced with the standard head coil at 7 T. Note that RD can only be safely ignored if τRD>>T2*.

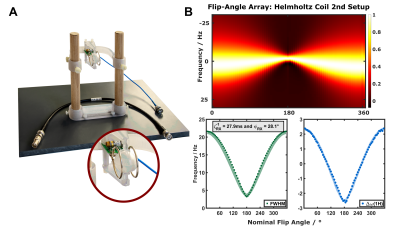

Experimental strategies to investigate the phase relation of the back-action field and the magnetization have not yet been suggested. The RADDSY approach assumes that the RD-field lags behind the transverse magnetization by 90°, which is only valid for a perfectly tuned coil. A deviation from this idealized assumption is shown in Figure 3B yielding ζRDrx≈36 s–1 and ψRDrx≈28°.

The proposed RADDEX experiment allows to evaluate the coil performance during Tx comparing RD-compensated composite RF pulses and standard composite pulses (Figure 2B). In particular, the extracted damping rate and phase term (ζRDtx≈44 s–1 and ψRDtx≈15°) reflect a deviation from perfect tuning and also a difference from the results in Rx mode.

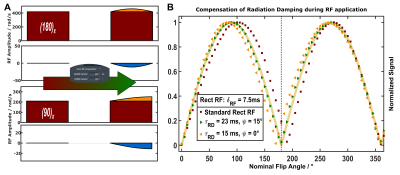

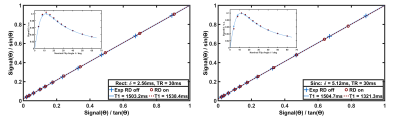

Compensation framework: To illustrate the validity of the fitted parameters obtained with RADDEX as well as the feasibility to effectively compensate RD during RF pulse application, the scanner’s user interface was appended to allow entering RD parameters and solve the Bloch-Maxwell equations during runtime. This achieved an individual adjustment of the pulse shapes (Figure 4A) depending on the nominal flip angle (α), pulse duration (δRF), ζRDtx and ψRDtx. Corresponding experiments revealed a striking resemblance between the expected sinusoidal oscillation of the signal strength as a function of the nominal flip angle and the results obtained with correctly applied RD compensation (Figure 4B).

Consequences for imaging sequences: To investigate the relevance of RD effects in human qMRI, simulation were performed for a steady-state gradient-echo measurement of T1 with variable flip angles12. Consistent with the preceding results, the obtained T1 estimate was impacted by relevant errors (>10%) in experimental settings that require longer pulse durations (Figure 5). Such deviations may lead to an overestimation of myelination or iron content in applications to study tissue composition.

Conclusion

The main focus of this study was on a detailed experimental investigation of RD effects during Rx and Tx without restriction to a perfectly tuned coil. Our results demonstrate the feasibility of a complete characterization of the spin-coil setup and may contribute to optimizing experimental strategies for qMRI in situations where RD cannot be ignored. They suggest that RD is not an exotic phenomenon restricted to very high magnetic fields but can occur in qMRI applications under specific conditions. While RD may not be relevant in the majority of human MRI acquisitions at 3 T or below, studies of post-mortem tissue specimens with dedicated coils supporting a high SNR can be significantly impacted. This applies to periods during application of RF pulses (e.g., affecting the effective flip angle) and all periods where transverse magnetization evolves without active gradients, with potentially striking manipulation of the magnetization trajectories.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] Bloembergen N, Pound RV. Radiation damping in magnetic resonance experiments. Phys. Rev. 1954;95(1):8-12.

[2] Hoult, D.I., Deslauriers, R. Elimination of signal strength dependency upon coil loading–an aid to metabolite quantitation when the sample volume changes. Magn. Reson. Med. 1990; 16:418-424.

[3] Louis-Joseph A, Abergel D, Lallemand JY. Neutralization of radiation damping by selective feedback on a 400-MHz NMR spectrometer. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;5(2):212-216.

[4] Zhou J., Mori S, van Zijl P. C. M. FAIR excluding

radiation damping (FAIRER). MRM 40(5): 712-719

[5] Bloom S. Effects of radiation damping on spin dynamics. J Appl Phys. 1957;28(7):800-805.

[6] Vlassenbroek A, Jeener J, Broekaert P. Radiation damping in high-resolution liquid NMR—a simulation study. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103(14):5886-5897.

[7] Pelupessy P. Radiation damping strongly perturbs remote resonances in the presence of homonuclear mixing. Magn Reson. 2022;3(1):43-51.

[8] Szantay C, Demeter A. Radiation damping diagnostics. Concepts Magn. Reson. 1999;11(3):121-145.

[9] Warren WS, Hammes SL, Bates JL. Dynamics of radiation damping in nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Chem. Phys. 1989;91(10):5895-5904.

[10] Guéron M. A coupled resonator model of the detection of nuclear magnetic resonance: Radiation damping, frequency pushing, spin noise, and the signal-to-noise ratio. Magn. Reson. Med. 1991;19(1):31-41.

[11] Hoult DI, Ginsberg NS. The quantum origins of the free induction decay signal and spin noise. J. Magn. Reson. 2001; 148:182-199.

[12] Brown RW, Cheng Y-CN, Haacke EM, Thompson MR, Venkatesan R. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Physical Principles and Sequence Design, Second Edition, Wiley, 2014; pp. 653-655.

Figures

Figure 2: (A) Overview of the RADDEX experiment comprising various excitation schemes based on composite pulses for an effective rotation of 90° or 180°, which differ in the level of RD compensation. (B) Experimental data recorded with the Helmholtz coil at 3 T (without RD compensation) as well as simulated curves based on the Bloch-Maxwell equations adjusted for T2*, offset frequency, ζRDtx and ψRDtx.

Figure 3: (A) Custom-built Helmholtz coil with spherical water phantom doped with MnCl2. (B) Normalized real part of spectra shown as stacked plot. Note the dependence of the full width at half maximum (FWHM) on the nominal flip angle, which is characteristic for RD during detection. The frequency shift of the maximum signal indicates a detuned coil setup with an additional phase term ψRDrx.

Figure 4: (A) Real-time compensation of RD during Tx mode. As examples, initially rectangular pulse shapes for flip angles of 180° and 90° are shown along with resulting modifications for RD compensation. (B) Experimentally measured signal intensities for an uncorrected pulse, RD-compensated pulse with appropriate parameters as well as a modified pulse with overestimated RD effects.

Figure 5: Simulation of a variable flip angle T1 measurements [4°, 8°, … 50°, 60°] with T1=1500ms and T2=250ms and ideal conditions (no B1 inhomogeneity) without (blue crosses) and with consideration of RD effects (red circles) characterized by an effective τRD=15 ms during Tx. The slope of the fitted straight line equals exp(–TR/T1). RD-related errors of the T1 estimate are negligible (<3%) for an RF pulse duration of 2.56 ms but relevant (12%) for a pulse duration of 5.12 ms.