1231

Experimental Validation of a PNS Optimized Body Gradient Coil1Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, United States, 2Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 3University Clinics Mannheim, Computer Assisted Clinical Medicine, Mannheim, Germany, 4Harvard Graduate Program in Biophysics, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, United States, 5Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Gradients, Gradients, gradient coil design, high-performance imaging

We report experimental PNS threshold measurements of an asymmetric PNS optimized whole-body gradient coil and compare it to a standard symmetric coil designed without PNS optimization. Stimulation thresholds were measured in 10 healthy adult subjects for five clinically relevant scan positions. The optimized design raised thresholds by up to 47% in four out of the five studied scan positions (head, cardiac, pelvic, and knee imaging positions). These results support the potential value of PNS-optimized asymmetric whole-body gradients for maximizing image encoding performancePurpose

Peripheral Nerve Stimulation (PNS) limits the usable image encoding performance of state-of-the-art body and head gradient coils [1-3]. We recently developed an approach to model and incorporate PNS metrics during the coil design phase to raise PNS thresholds and maximize image encoding performance [4]. We previously designed a pair of actively shielded torque/force balanced Y-axis body coils (one with PNS optimization, one without) and compared their PNS performance in modeling studies [5]. In this work, we constructed prototypes of these two coils and validated the predicted PNS changes with experimental threshold measurements in ten healthy volunteers.Methods

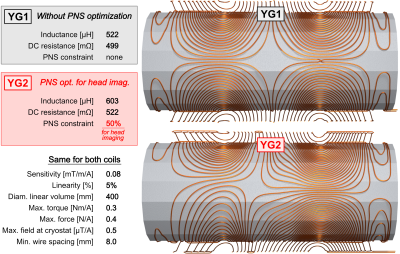

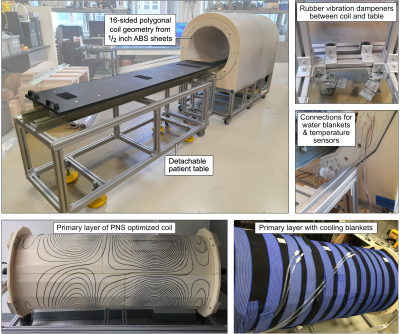

Coil design: We designed two actively shielded whole-body Y-axis gradient coils (YG1 and YG2, Fig. 1) using our PNS-constrained design framework [4]: YG1 is a conventional design without PNS optimization while the YG2 design includes an additional PNS constraint. PNS thresholds of YG2 were constrained to be 50% higher than those of YG1 for the head imaging landmark while allowing a 15% inductance increase. The two coils have otherwise identical design constraints and dimensions, and are both torque and force balanced. Both coils have relatively small inner diameter (and thus low inductance) to ensure that stimulation can be achieved in both coils.Coil construction: The coil formers consist of flat ABS sheets with milled dovetail groves for the winding pattern. The ABS sheets were bent and assembled, yielding a polygonal coil geometry. The 3.2 mm diameter enameled copper wire was hammered into the groove, and the coil was covered in epoxy-soaked fiber glass for mechanical stability. The coils’ construction method limits their use to PNS experiments outside of a static magnet field. The primary layer was cooled with water blankets. The coil cart and the patient table were constructed from T-slotted aluminum frames. We mechanically isolated the cart and patient table using rubber dampeners to reduce the risk of false PNS positives due to table vibrations.

PNS Experiments: A preliminary experimental PNS study was performed under IRB approval and with written informed consent using 10 healthy adult volunteers (4 males, 6 females), average age 37 ± 16 years (min. 25, max. 69), weight 68.6 ± 13.9 kg (min. 49.4, max. 88.4), and height 169.3 ± 7.3 cm (min. 160, max. 182.9). The stimulation waveforms consisted of 16 bipolar trapezoidal pulses with varying rise times (100 to 500 μs) and amplitudes, and constant flat-top duration (500 μs). Thresholds for both coils YG1 and YG2 were assessed in a single session to reduce intra-subject variability from weight gain/loss, level of hydration, etc. Changing the experimental setup from YG1 to YG2 took approximately 10 minutes. For each subject and coil, we measured thresholds at five different scan positions, mimicking head and cardiac imaging (head-first supine) as well as abdominal, pelvic, and knee imaging (feet-first supine), yielding a total of ten threshold curves per subject for the 1.5h experiment.

Results

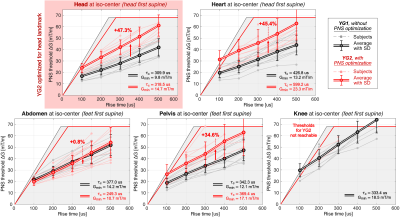

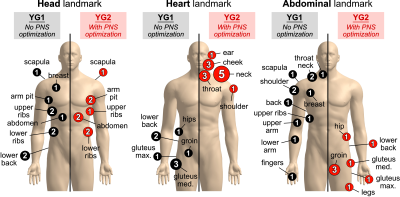

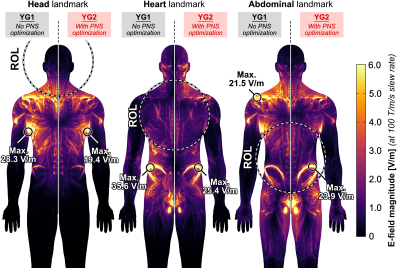

Figure 2 shows photographs of the experimental setup. The coil temperature change was ΔT ≤ 5°C over the course of the stimulation experiment thanks to the low duty cycle (one pulse every 3 seconds) and cooling using chilled water blankets. Figure 3 shows PNS threshold curves for both the unoptimized coil (YG1, black curves) and the coil optimized for head imaging (YG2, red curves) for all five scan positions. PNS optimization raised thresholds by 47.3% for head imaging. For cardiac and pelvic imaging, PNS thresholds were raised by 45.4% and 34.6%, respectively, despite the coil not being explicitly optimized for these scan positions. For knee imaging, the PNS thresholds of YG2 were not reached for most of the subjects, yielding an estimated worst-case threshold improvement of 21.5% (assuming thresholds just outside the operational parameter space). PNS thresholds for abdominal imaging did not change between the optimized and unoptimized coils. Figure 4 summarizes the sites of perceived sensation reported by the subjects for three of the five scan positions and both coils. For head imaging, the sites of perception remained similar between YG1 and YG2. For cardiac imaging, reported perceptions shifted from the pelvis to the shoulder/neck region. For abdominal imaging, stimulation sites shifted from the torso and abdomen to the pelvis. Figure 5 shows maximum intensity projections of the simulated E-field at 100 T/m/s for three of the five scan positions and both coils (YG1: left half of each panel; YG2: right half). For head and cardiac imaging, YG2 lowered the peak E-fields induced in the body, leading to the PNS threshold improvements shown in Fig. 3. For abdominal imaging, YG2 led to slightly higher E-fields.Conclusion

We constructed a prototype asymmetric PNS-optimized whole-body gradient coil and compared it to its unoptimized counterpart. The optimized coil has approx. 15% higher inductance and 5% higher resistance but otherwise identical properties (gradient field efficiency, linearity, wire spacing/bend radii, torque/force balancing, and coil former geometry). The PNS-optimized coil raised thresholds by up to 47.3% in four of the five analyzed clinically relevant scan positions. For abdominal imaging, the PNS optimization did not significantly affect the thresholds. This study demonstrates the ability of asymmetric whole-body gradient coils to substantially raise thresholds when designed with explicit PNS constraints, thereby maximizing the usable image encoding performance.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of past and present members of the gradient coil group at Siemens Healthineers, including Peter Dietz, Gudrun Ruyters, Axel vom Endt, Ralph Kimmlingen, Franz Hebrank, and Eva Eberlein. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and the National Institute for Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers U01EB025162, P41EB030006, U01EB026996, R01EB028250, U01EB025121. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.References

[1] Setsompop et al., “Pushing the limits of in vivo diffusion MRI for the human connectome project”, NeuroImage, vol. 80, pp. 220 – 233, 2013

[2] McNab et al., “The human connectome project and beyond: Initial applications of 300 mT/m gradients”, NeuroImage, vol. 80, pp. 234 – 245, 2013

[3] Tan et al., “Peripheral nerve stimulation limits of a high amplitude and slew rate magnetic field gradient coil for neuroimaging”, Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 83, no. 1, pp. 352–366, 2020.

[4] Davids et al., “Optimization of MRI Gradient Coils with Explicit Peripheral Nerve Stimulation Constraints”, IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 2020, 40, 129-142

[5] Davids et al., “Design Analysis and Prototype Construction of PNS Optimized MRI gradient coils”, Proceedings of the 29th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, London, UK, 2022

Figures