1223

Probing Possible Composition Changes of Placenta over Gestation Age Using Diffusion‐Relaxometry Correlated Spectroscopy Imaging

Xilong Liu1, Chantao Huang1, Wentao Hu2, Jie Feng1, Wenjun Qiao1, Sijin Chen1, Bo Liu1, Yongming Dai2, and Yikai Xu1

1Department of Medical Imaging Center, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China, 2MR Collaboration, Central Research Institute, United Imaging Healthcare, Shanghai, China

1Department of Medical Imaging Center, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China, 2MR Collaboration, Central Research Institute, United Imaging Healthcare, Shanghai, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Placenta, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques

Currently, antenatal noninvasive imaging techniques to directly evaluate placental function remains challenge. The objective of this study was using diffusion-relaxometry correlated spectrum imaging (DR-CSI) as a tool to probe the possible placental composition changes over gestation in normal pregnancy. Four to five peaks were visible in the D-T2 spectrum for most subjects. DR-CSI compartments were defined according to peak distribution. Significant correlation between DR-CSI compartment volume fractions and GA was found. We suggested that the DR-CSI technique could be used to reveal features of placental composition.Introduction

Placenta plays a vital role for fetal growth and development during pregnancy. Major pregnancy complications, such as fetal growth restriction, preeclampsia, and preterm birth, have been linked with placental dysfunction [1-3]. However, current antenatal assessment of placental function is limited. Placental MRI, which can provide in vivo assessment of the placenta structure and function, is emerging as a technique with substantial promise to overcome some disadvantages of ultrasound. Diffusion-relaxometry correlation spectrum imaging (DR-CSI) provides both spectral and spatial information for different intra-voxel compositions. This study is aimed to 1) Obtain the typical characteristics of D-T2 spectrum for healthy placenta; 2) elucidate the possible placental composition change over gestation in normal pregnancy using DR-CSI.Methods

Forty singleton pregnancies, with a mean ± SD (range) GA 30.27±3.28 (23-36) weeks at time of examination, were included. Estimated fetal weight (eFW) was calculated according to an ultrasound examination. All MRI examinations were performed on a 3.0T scanner (uMR780, United Imaging Healthcare, Shanghai, China). DR-CSI scans were performed using spin-echo echo-planar diffusion-weighted-imaging (SE-EP-DWI) sequence, with 7 b-values (01, 101, 251, 1001, 2001, 6001, 10002 s/mm2) combining 4 TEs (78, 114, 150, 184 ms). Acquired DR-CSI signal of a particular voxel i isSi (b,TE )= ∫∫ fi(D,T2)*e-bD*e-TE/T2 dD dT2

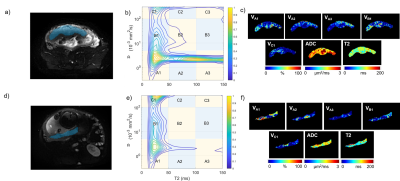

where fi is spectral intensity representing the compositional distribution in D-T2 dimensions. Regions of interests (ROIs) were defined inside placenta on all 5 slices. Spectra were constructed in the range: D 0.3~300 μm2/ms, T2 of 0~150 ms. All spectra were segmented into 9 compartments, A1(low D, short T2), A2(low D, mediate T2), A3(low D, long T2), B1(mediate D, short T2) …C3(high D, long T2) by 4 boundaries (decided by general peak distribution): 5, 100 μm2/ms for D and 50, 100 ms for T2 (Figure 1).

Volume fraction Vm of each compartment m was obtained voxel-by-voxel, and mean Vm of whole ROI was calculated for each participant. Inter-class coefficient (ICC) was used to assess the inter-observer agreement. ICC>0.8 was defined as good. The relationships of Vm to GA and eFW were evaluated by Pearson correlation. A p-value <0.05 was regarded statistically significant.

Results

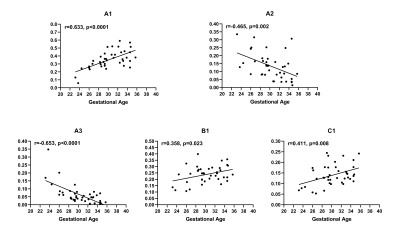

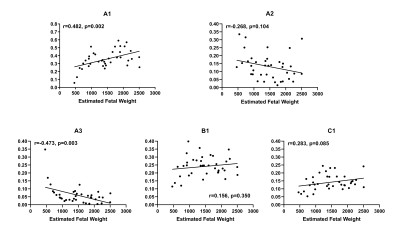

Four to five peaks could be observed in the spectrum for most subjects (Figure 1). Three peaks could be observed at low T2 (<50ms), with totally different diffusivity (< 101, ~ 101 and > 102 μm2/s separately). Another one or two peaks could be observed at low diffusivity (~ 2μm2/s) and longer T2 (>50ms).After spectra segmentation. Compartment A1(averaged 35.5±11.2% for the whole cohort), B1(23.9±6.6%), C1(14.0±5.0%), A2(13.4±8.3%) and A3(6.3±6.2%) have nonnegligible volume fractions. Other compartments (B2, C2, B2, C3) showed low concentration (average V<3%) and were excluded for further analysis. Inter-observer agreement was good for all Vm. DR-CSI VA1 (r=0.633, p<0.001), VB1 (r=0.358, p=0.023), VC1 (r=0.411, p=0.008) showed positive correlation with GA. VA2 (r=−0.465, p=0.003) and VA3 (r=−0.653, p<0.001) showed negative correlation with GA (Figure 2). VA1 (r=0.482, p=0.002) and VA3 (r=−0.473, p=0.003) showed significant correlation with eFW. No significant correlation was found for eFW to VA2, VB1 and VC1 (Figure 3). Vm mappings were obtained for each participant.

Discussion

Placenta has two different and non-contacting circulations. The fetal circulation is intra-capillary and has relatively high-velocity flow and a low oxygen saturation, whilst the maternal circulation is a low-velocity and a highly-saturated blood pool but is extra-vascular in the human placenta [4,5]. Therefore, the compartments A2, A3 (mediate/high T2, low D) should be associated to slow-moving maternal blood, whereas the compartment C1 (low T2 and high D) should be associated with fetal blood. The fluid across the fetal-maternal barrier, which experiences active filtration in the trophoblast compartment, was considered to display an intermediate diffusivity in previous studies [6,7]. Thus, it is reasonable to associate compartment B1 to this filtrating flow. Finally, the signal contribution from compartment A1 (low T2, low D), would be associated with the dense tissue. Notice that spectra intensity of ultra-low diffusivity (<1μm2/s) was concentrated in A1, possibly explained by cellularity-induced restriction.As the placenta grows and matures, the diffusion, perfusion, and heterogeneity of the placenta change accordingly. The correlation between DR-CSI Vm and GA may be explained by the normal placental maturation, which includes morphologic changes evolving during gestation, such as increase in number of terminal villi, vascular surface area, decrease in average vessel diameter, and increase intervillous fibrin deposition [8,9]. Additionally, the change in the fraction between maternal and fetal blood also contributes to the evolution of diffusivity and relaxometry [10].

Conclusion

D-T2 spectra and volume fraction mappings for normal placenta were obtained. Correlation of possible placenta composition with gestation were obtained, suggesting its potential for assessing placental function during pregnancy.Acknowledgements

We thank all the women who participated in the study, their obstetricians involved in study recruitment. The authors express their appreciation to their volunteers for participating in this study.References

- R. L. Zur, J. C. Kingdom, W. T. Parks and S. R. Hobson. The Placental Basis of Fetal Growth Restriction. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America 2020; 47: 81-98. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2019.10.008.

- A. E. P. Ho, J. Hutter, L. H. Jackson, P. T. Seed, L. McCabe, M. Al-Adnani, A. Marnerides, S. George, L. Story, J. V. Hajnal, M. A. Rutherford and L. C. Chappell. T2* Placental Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Preterm Preeclampsia: An Observational Cohort Study. Hypertension 2020; 75: 1523-1531. DOI 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.14701.

- M. C. Audette and J. C. Kingdom. Screening for fetal growth restriction and placental insufficiency. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 2018; 23: 119-125. DOI 10.1016/j.siny.2017.11.004.

- A. Melbourne, R. Aughwane, M. Sokolska, D. Owen, G. Kendall, D. Flouri, A. Bainbridge, D. Atkinson, J. Deprest, T. Vercauteren, A. David and S. Ourselin. Separating fetal and maternal placenta circulations using multiparametric MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine 2019; 81: 350-361. DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.27406.

- G. J. Burton and A. L. Fowden. The placenta: a multifaceted, transient organ. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2015; 370: 20140066-20140066. DOI 10.1098/rstb.2014.0066.

- P. J. Slator, J. Hutter, M. Palombo, L. H. Jackson, A. Ho, E. Panagiotaki, L. C. Chappell, M. A. Rutherford, J. V. Hajnal and D. C. Alexander. Combined diffusion-relaxometry MRI to identify dysfunction in the human placenta. Magnetic resonance in medicine 2019; 82: 95-106. DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.27733.

- E. Solomon, R. Avni, R. Hadas, T. Raz, J. R. Garbow, P. Bendel, L. Frydman and M. Neeman. Major mouse placental compartments revealed by diffusion-weighted MRI, contrast-enhanced MRI, and fluorescence imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111: 10353-10358. DOI 10.1073/pnas.1401695111.

- C. Wright, D. M. Morris, P. N. Baker, I. P. Crocker, P. A. Gowland, G. J. Parker and C. P. Sibley. Magnetic resonance imaging relaxation time measurements of the placenta at 1.5T. Placenta 2011; 32: 1010-1015. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2011.07.008.

- M. Sinding, D. A. Peters, J. B. Frøkjær, O. B. Christiansen, A. Petersen, N. Uldbjerg and A. Sørensen. Placental magnetic resonance imaging T2* measurements in normal pregnancies and in those complicated by fetal growth restriction. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2016; 47: 748-754. DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.14917.

- J. Hutter, A. Ho, L. H. Jackson, P. J. Slator, L. C. Chappell, J. V. Hajnal and M. A. Rutherford. An efficient and combined placental -ADC acquisition in pregnancies with and without pre-eclampsia. Magnetic resonance in medicine 2021; 86: 2684-2691. DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.28809.

Figures

Figure 1 Panels a-c: A pregnant women with gestation age of 24W+3D; Panels d-f: A

pregnant women with gestation age of 32W+5D. a) and d) DWI images (TE78, b100)

with ROI of placenta; b) and e) D-T2 spectrum segmented into nine compartments;

c) and f) Volume fraction maps of A1, A2, A3, B1, C1, mean T2 and ADC.

Figure 2 Scatterplot and linear regression of DR-CSI volume fractions (A1, A2, A3, B1

and C1 respectively) with gestation age. Positive

correlation could be found for VA1, VB1 and

VC1 with

gestation age. Negative correlation could be found for VA2 and

VA3 with

gestation age.

Figure 3 Scatterplot and linear regression of volume fractions (A1, A2, A3, B1 and C1

respectively) with estimated fetal weight. Positive

correlation could be found for VA1 with

estimated fetal weight. Negative correlation could be found for VA3 with

estimated fetal weight. Correlation for VA2, VB1 and

VC1 with

estimated fetal weight is not significant.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1223