1207

Functional brainstem imaging of sympathetic drive using MSNA coupled fMRI and SSNA coupled fMRI at ultra-high field.

Rebecca Glarin1, Luke Henderson2, Donggyu Rim3, and Vaughan Macefield3

1University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia, 2University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 3Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, Prahran, Australia

1University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia, 2University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 3Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, Prahran, Australia

Synopsis

Keywords: Nerves, High-Field MRI, Brainstem

Muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) is responsible for blood pressure control and skin sympathetic nerve activity (SSNA) for thermoregulation. This activity can be recorded through a process of microneurography. This nerve activity can be temporally coupled with fMRI to image the brainstem. With the use of ultra high field MRI we are able to image the subcortical and cortical regions responsible for these sympathetic nervous system processes. Brainstem imaging using this technique for the first time at high field, has identified with high specificity the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) when using MSNA coupled fMRI.Introduction

The sympathetic nervous system is responsible for the homeostatic control of many physiological processes. Sympathetic outflow is generated within specific nuclei in the brainstem and hypothalamus (Dampney, 1994), with contributions from other subcortical and cortical sites. This outflow is responsible for regulation processes but specifically for this study, blood pressure and thermoregulation. Muscle Sympathetic Nerve Activity (MSNA) contributes to the beat-to-beat regulation of blood pressure through its control of arteriolar diameter within the highly vascularised skeletal muscle bed (Charkoudian, 2014). Skin Sympathetic Nerve Activity (SSNA) contributes to thermoregulation through cutaneous vasoconstriction, vasodilation and sweat release. This activity can be detected as MSNA and SSNA and recorded directly via intraneural microelectrodes (Vallbo, 1979). This technique results in a neurogram displaying the nerve activity and is known as microneurography. The lab has previously developed the techniques of MSNA-coupled and SSNA-coupled functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). This has been performed with a 3 Tesla MRI (Macefield, 2010). Further extension of this method is being undertaken at Ultra-high field on a 7T MRI. This promises higher spatial resolution, particularly of the brainstem and hypothalamus, than we could previously achieve. We aim to functionally identify the brainstem nuclei responsible for generating sympathetic drive through the use of ultra-high field (7T), high-resolution fMRI coupled with direct recordings of sympathetic nerve activity to muscle and skin.Methods

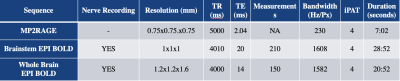

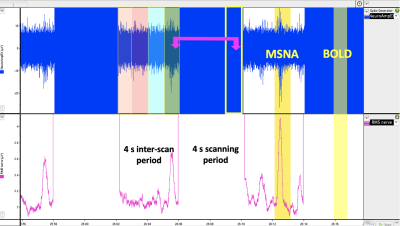

Recording procedures: A tungsten microelectrode was inserted percutaneously into a muscle fascicle of the common peroneal nerve at the fibular head of 18 participants (8 MSNA, 10 SSNA). Neural activity was amplified (gain 20 000, bandpass 0.3-5.0 kHz) using a low-noise headstage (NeuroAmpEX, ADInstruments, Australia) and spontaneous bursts of MSNA or SSNA identified and burst amplitudes measured using analysis software (Labchart). This neurogram is recorded throughout scanning with the participant at rest.Imaging procedures: Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) contrast - gradient echo, echo-planar images were collected in the axial plane, on a 7T Magnetom Plus (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with a 1Tx32Rx channel head coil (Nova Medical, Wilmington, MA, USA). The two fMRI sequences cover brainstem and whole brain respectively and are scanned with the participant at rest and the nerve recording active. The sequences are run adopting a 4s-ON, 4s-OFF triggered protocol (Fig 1). This is with consideration of the timing of both the neural conduction delay and BOLD haemodynamic delay. The interscan delay of 4 seconds accommodates a 1 second neural delay with the addition of the 4 second interscan delay completing the timing of the 5 second heamodynamic delay. It is important to note this interscan delay is required due to the noise produced on the neurogram by the scanner gradients. This noise blocks out the nerve signal completely hence the necessity of the interscan delay. (Fig 2). The data must be divided into four, one second epochs and the analysis model must adopt both the presence of a nerve burst per 1 second epoch and the equivalent epoch in the bold signal (Fig 3).

Results

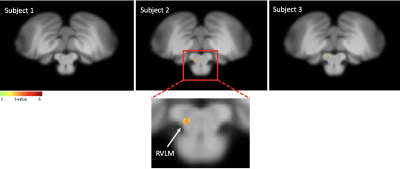

Preliminary analysis of the neurogram and brainstem fMRI has been performed in 3 of 8 successful MSNA recordings in healthy participants (Fig 4). In these axial brainstem sections MSNA-coupled increases in BOLD activation were detected at the level of the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) in each participant. As the same technique is adopted for the SSNA recordings we expect the same specificity on the BOLD signal in the brainstem for this data set.Conclusion

These preliminary results indicate that, using MSNA-coupled fMRI, we can detect increases in BOLD signal intensity in RVLM with 1 mm isotropic voxels. The improved signal to noise and higher resolution available at ultra-high field will allow us to image the small medullary nuclei responsible for generating sympathetic drive with higher precision.Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments the facilities, scientific and technical assistance from the National Imaging Facility, a National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy capability, at the Melbourne Brain Centre Imaging Unit, The University of Melbourne. This work was supported by a research collaboration agreement with Siemens Healthineers.References

Charkoudian, N., Wallin, B.G., 2014. Sympathetic neural activity to the cardiovascular system: integrator of systemic physiology and interindividual characteristics. Compr Physiol 4, 825-850.

Dampney, R.A., 1994. Functional organization of central pathways regulating the cardiovascular system. Physiol Rev 74, 323-364.

Macefield, V.G., Henderson, L.A., 2010. Real-time imaging of the medullary circuitry involved in the generation of spontaneous muscle sympathetic nerve activity in awake subjects. Hum Brain Mapp 31, 539-549.

Vallbo, A.B., Hagbarth, K.E., Torebjork, H.E., Wallin, B.G., 1979. Somatosensory, proprioceptive, and sympathetic activity in human peripheral nerves. Physiol Rev 59, 919-957.

Figures

Fig 1. Sequence parameters

Fig 2. Interscan delay considerations - neural delay (1second) and haemodynamic delay (5 seconds) requiring a 4 second interscan delay.

Fig 3. Acquisition timing - Burst of MSNA recorded (Labchart) every 4 seconds displaying the interscan delay. The recording must be divided in to one second epochs (orange, pink, blue, green). The

presence of a nerve burst per one second epoch and the equivalent epoch in the bold signal must be correlated for analysis purposes (yellow).

Fig 4. Results - Axial slice at the level of medulla on three healthy controls, displaying

an increase in BOLD signal when coupled with muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) in the region of rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1207