1203

Gender differences in brain response to infant emotional faces1School of psychology, Shandong Normal University, Ji’nan, China, 2Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 3Department of Medicine Imaging, The People's Hospital of Jinan Central District, Jinan, China, 4School of information science and engineering, Linyi University, Linyi, China, 5College of Medical Imaging, Shanghai University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Shanghai, China, 6Department of Psychology, Shanghai University of Sport, Shanghai, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Nerves, fMRI (task based), Infant emotional faces, Empathy

Exploring the neural processes of recognizing infant stimuli promotes better understandings of the mother-infant attachment mechanisms. Here combining Task-fMRI and resting-state fMRI investigated the effects of infants’ emotional faces on the brain activity of women and men. The task-fMRI showed that the brains of women and men reacted differently to infants’ faces, and these differential areas are in facial processing and empathetic networks. The rs-fMRI further showed that the connectivity of the default-mode network-related regions increased in women than men. These differences might facilitate women to more effective and quick adjustments in behaviors and emotions during the nurturing infant period.Introduction

Adult and infant interaction relies heavily on the ability to receive and express nonverbal emotional signals through facial expressions. These nonverbal emotional signals including infant emotional sounds or facial expressions, can attract the attention of adults and communicate their needs, thereby obtaining caregivers’ care and protection1. Human infants depend on sensitive and adaptive caregiving behaviors from adults for living2. Both women and men can provide caregiving behaviors for their infants. However, traditionally, women take responsibility for early childcare, whereas men have little direct investment in offspring3. Anthropological evidence has indicated that women are the primary caregivers of infants in the vast majority of cultures, whereas men are seen as more powerful and separated from the family4. Thus, biological or cultural factors (such as gender or social status) may produce different parenting behavioral responsiveness to infants in women and men. Here, to identify the brain processing that underlies nulliparous women’s and men’s general propensity to respond to infant emotional faces, we recorded a task-fMRI from nulliparous women and men while they processed infant emotional faces. Further, differential brain regions in directional responses to infant emotional faces were selected as ROIs, then we used FC method to delineate their functional characterizations using the rs-fMRI data. Using a multimodal fMRI, we aimed at providing a comprehensive characterization of regions that showed differential brain activation respond to infant emotional faces by analyzing interactions of their functional connections.Methods

Two groups of healthy volunteers including 26 nulliparous women (M = 26.68, SD = 1.84) and 25 men (M = 26.54, SD = 1.92) were recruited. Subjects were presented with infant facial pictures in the scanner. Every picture was present with 2s randomly, then followed by an average 4s fixation cross (ranging from 2s - 6s). The experimental paradigm was composed of 120 trials in total. This task has 363 volumes. The MRI scanning was performed on a Siemens 3.0 T Trio Tim MR system. Anatomical images were collected with the following acquisition parameters: TR = 2530 ms, TE = 2.34 ms, FOV = 256 mm, 192 slices. Functional images with the following parameters: TR = 2000 ms, TE = 30 ms, FOV = 220 × 220 mm2, 33 slices, slice thickness = 3.5 mm. During the resting-state fMRI scan, all subjects were instructed to rest, relax, and not think of anything, with their eyes closed. Task-fMRI data were analyzed for exploring the differential activation between women and men. Functional connectivity was analyzed using rs-fMRI data.Results

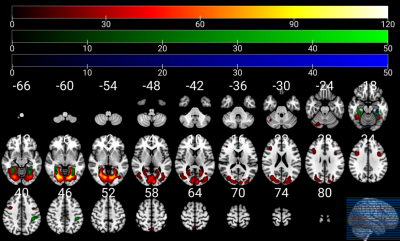

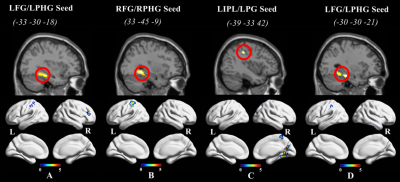

Compared to men, nulliparous women showed significant differences in EC scores(p = 0.027). Compared with men, the neural activation in nulliparous women increased in several regions during the processing of infant emotional faces, such as visual areas (fusiform gyrus, inferior and middle occipital gyri, and lingual gyrus), limbic areas (parahippocampal gyrus and posterior cingulate cortex), temporoparietal areas (parietal lobule and middle temporal gyrus), temporal areas (middle temporal gyrus), and the cerebellum. This neural network is the most likely to be activated while processing the infant emotional faces (Figure 1). We further investigated FC in resting-state networks that showed significant differential neural activation in response to emotional infant stimuli. Relative to men, some brain regions of the default model network (DMN) in nulliparous women showed increased connectivity (e.g. inferior parietal lobule, postcentral gyrus, precuneus, and middle temporal gyrus) (Figure 2).Discussion

A review study identified that emotional face-specific clusters were involved in face processing, including the fusiform gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, inferior frontal cortex 5. Our results reflected that several functional neural networks in nulliparous women that activated in response to infant emotional faces and overlapped the brain basis of human mothering, including maternal brain circuit, attention, facial visual cortex, and emotional modulation areas. The findings might suggest that complex infant cues require the allocation of attentional, empathetic, motivational resources in the brains of women to respond appropriately to them. Paola Rigo et al., reported the similar results using the infant sound as stimuli, which infant sounds affect women and men differently 6,7, Moreover, reduced rs-FC in DMN regions involved in social cognition was found in postpartum depression 8. Thus, greater DMN functional connectivity in the current study might provide new insight for understanding the neural mechanism of parental rearing behaviors.Conclusion

Results suggest a gender difference in brain responses to infant emotional faces, especially regarding the activation of the facial processing, and empathetic system. Researchers reported that sex differences in the frequency of nurturing behaviors 9,10, in other words, males interacted less with the infant than did females. In childless adults, women showed relatively greater preferences for infants than men 11 which this kind of sex difference may represent a biological adaptation for parenting 12. Hence, the differential brain function between nulliparous women and men may be explained to some extent on the cause of the behavior differences. These functional and behavioral differences in nulliparous women and men may promote females to adapt and adjust behaviors and emotions in favor of nurturing infants quickly when they experience pregnancy. These findings have implications for understanding the neural processing mechanism of nulliparous women and men respond to infant emotional faces.Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 32200915). We would like to acknowledge the dedication of all the participants involved in this research.References

1. Wynne-Edwards, K. E. Mother Nature: A History of Mothers, Infants, and Natural Selection.: By Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, New York: Pantheon Books, 1999, 541 pages text + index + notes, ISBN: 0679442650, $35.00 (US). Evolution & Human Behavior 21, 219-221 (2000).

2. Senese, V. P. et al. Human infant faces provoke implicit positive affective responses in parents and non-parents alike. PLoS One 8, e80379, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080379 (2013).

3. Clutton-Brock, T. H. Mammalian mating systems. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 236, 339-372, doi:10.1098/rspb.1989.0027 (1989).

4. Boorman, R. J., Creedy, D. K., Fenwick, J. & Muurlink, O. Empathy in pregnant women and new mothers: a systematic literature review. J Reprod Infant Psychol 37, 84-103, doi:10.1080/02646838.2018.1525695 (2019).

5. Sabatinelli, D. et al. Emotional perception: Meta-analyses of face and natural scene processing. NeuroImage 54, 2524-2533, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.011 (2011).

6. De Pisapia, N. et al. Sex differences in directional brain responses to infant hunger cries. Neuroreport 24, 142-146, doi:10.1097/WNR.0b013e32835df4fa (2013).

7. Rigo, P. et al. Brain processes in women and men in response to emotive sounds. Social neuroscience 12, 150-162, doi:10.1080/17470919.2016.1150341 (2017).

8. Chase, H. W., Moses-Kolko, E. L., Zevallos, C., Wisner, K. L. & Phillips, M. L. Disrupted posterior cingulate-amygdala connectivity in postpartum depressed women as measured with resting BOLD fMRI. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience 9, 1069-1075, doi:10.1093/scan/nst083 (2014).

9. Martin, R. D. & MacLarnon, A. M. Gestation period, neonatal size and maternal investment in placental mammals. Nature 313, 220-223, doi:10.1038/313220a0 (1985).

10. Christov-Moore, L. et al. Empathy: gender effects in brain and behavior. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 46 Pt 4, 604-627, doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.09.001 (2014).

11. Charles, N. E., Alexander, G. M. & Saenz, J. Motivational value and salience of images of infants. Evol Hum Behav 34, 373-381, doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2013.06.005 (2013).

12. Maestripieri, D. & Pelka, S. Sex differences in interest in infants across the lifespan : A biological adaptation for parenting? Hum Nat 13, 327-344, doi:10.1007/s12110-002-1018-1 (2002).

Figures