1188

3D quantitative-amplified Magnetic Resonance Imaging (3D q-aMRI)1Electrical Engineering, Stanford, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Radiology, Stanford, Stanford, CA, United States, 3Mātai Medical Research Institute, Tairāwhiti-Gisborne, New Zealand, 4Neurology & Neurological Sciences, Stanford, Stanford, CA, United States, 5Mechanical Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States, 6Computing and Mathematical Sciences (CMS), Cal Tech, Pasadena, CA, United States, 7Auckland Bioengineering Institute, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 8General Electric Healthcare, Victoria, Australia, 9Neurology, Stanford, Stanford, CA, United States, 10Faculty of Medical & Health Sciences & Centre for Brain Research, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Data Processing, amplified MRI (aMRI), Alzheimer`s disease

Amplified Magnetic Resonance Imaging (aMRI) is a pulsatile brain motion visualization method that delivers ‘videos’ with high contrast and temporal resolution. aMRI has been shown to be a promising tool in various neurological disorders. However, aMRI currently lacks the ability to quantify the sub-voxel motion field in physical units. Here, we introduce a quantitative-aMRI (q-aMRI) algorithm, which quantifies the sub-voxel motion of the 3D aMRI signal and validates its precision using phantom simulations with realistic noise. In-vivo experiments on healthy volunteers demonstrated repeatability of the measurements, and differences in brain motion were observed in subjects with positive/negative amyloid PET.Introduction

Amplified Magnetic Resonance Imaging (aMRI) has been introduced as a new brain motion detection and visualization method1-4. aMRI has been applied in Chiari Malformation2,5, aneurysms6 (aFlow), hydrocephalous7 and concussion8 applications. In particular, the 3D aMRI3,4 approach has come with dramatic improvements at detecting brain motion. However, 3D aMRI lacks the ability to quantify the sub-voxel motion field in physical units. Here, we introduce a novel 3D quantitative-aMRI (3D q-aMRI) algorithm which quantifies the sub-voxel motion field of the 3D aMRI signal.Method

Human subjects:Experiments were conducted under ethical approval from The University of Auckland and Stanford University. Seven healthy adult volunteers were scanned (4-Males and 3-Females between 21-37 years), with additional scans acquired on two volunteers 2-21 days later. Data were also acquired on subjects with positive amyloid PET (73-years-old with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), heart rate = 62-BPM) and healthy control (74-years-old, heart rate = 50-BPM).

MRI acquisition:

A 3T MRI scanner (SIGNA Premier; GEHealthcare) was used with an AIR™ 48-channel head coil. 3D volumetric cardiac-gated cine (bSSFP/FIESTA) MRI datasets were acquired as follows: Sagittal plane, FOV = 24 x 24 cm, matrix size = 256 × 256, TR/TE/flip-angle = 2.9 ms/1 ms/25°, acceleration = 8, resolution = 1.2 mm isotropic, peripheral pulse gating with retrospective binning to 20 cardiac phases, 116 slices, and a scan time of ~2:30 min.

Motion Quantification:

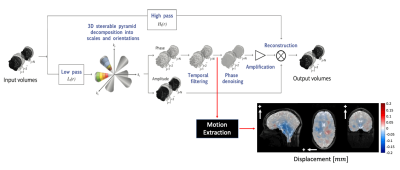

Fig. 1 illustrates the 3D q-aMRI algorithm pipeline3. The quantification step is shown at the point at which the local phases (derived from the 3D complex-valued steerable pyramid9,10) are temporarily band-passed filtered. The band-passed phases continue through two routes: (1) through the original 3D aMRI algorithm, which results in motion magnification, and (2) through the quantification algorithm. The algorithm is based on solving the optical flow equation, but instead of solving it over the image intensities, we solve it over the filtered phases in a weighted least square fashion11,12 as follows:

$$$ arg \ min_{u,v,d} \sum_{w} \sum_i A^2_{r_i,\theta_i}\left[\left(\frac{\partial\phi_{r_i,\theta_i}}{\partial x},\frac{\partial\phi_{r_i,\theta_i}}{\partial y}, \frac{\partial\phi_{r_i,\theta_i}}{\partial z} \right)\cdot\left(u,v,d\right) - \triangle\phi_{r_i,\theta_i} \right]^2$$$

where $$$u, v$$$ and $$$d$$$ are the estimated motion field. $$$W$$$ is a Gaussian window with $$$ \sigma = 5 $$$ and a support of $$$21 \times 21 \times 21$$$ pixels, $$$ \phi_{r_i,\theta_i}$$$ and $$$ A_{r_i,\theta_i} $$$ are the phase and amplitude response of the $$$ith$$$ level of the 3D steerable pyramid, and $$$\triangle\phi_{r_i,\theta_i}$$$ is the phase difference between the frames $$$t_i $$$ and $$$t_0$$$. This approach has the advantage over traditional intensity based tracking methods of been able to quantify motion down to 0.001 of pixel size13,14.

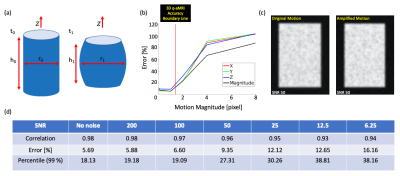

Digital Phantom Simulation:

3D q-aMRI was tested on a 3D digital phantom which mimics the subtle deformation, intensity, and contrast of the lateral ventricles observed in 3D aMRI (Fig. 2a). The algorithm performances were evaluated using the following metrics:

1. Pearson’s Linear Correlation

2. $$$ Error = Mean \left[abs\left(\frac{X_{estimated} - X_{true}}{X_{true}}\right)*100\right] \ [\%] $$$

3. 99-percentile of the Error distribution

In-Vivo Validation:

3D q-aMRI was compared to 3D aMRI. The repeatability and reproducibility of 3D q-aMRI was evaluated. Finally, 3D q-aMRI was applied to patients with positive/negative amyloid PET.

Results

Phantom Simulations:Fig. 2b shows the motion estimation error in the absence of noise. The algorithm is accurate for sub-voxel motion as small as ~0.0001 of a pixel size, but breaks for large motions > 1.5 pixels. Fig. 2d suggests that with added noise, 3D q-aMRI can robustly quantify motion > 0.005 of a pixel size i.e. ~6$$$\mu m$$$ (in our acquisition protocol), for an SNR of as low as 25. An example of the original and amplified extracted motion field for an SNR of 50 is shown in Fig. 2c.

In-Vivo Data:

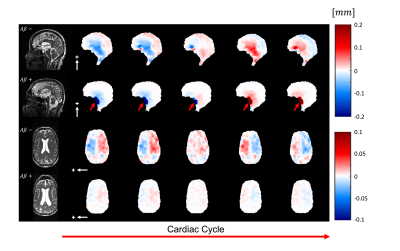

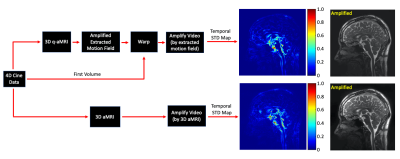

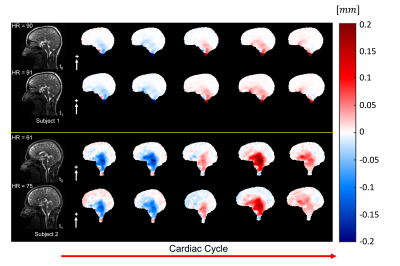

Fig. 3 shows the outputs of 3D q-aMRI and 3D aMRI, and their corresponding normalized temporal variance maps. The results suggest that 3D q-aMRI successfully quantified the 3D aMRI signal. Fig. 4 shows that the brain motion for the repeated scans is similar for different days on both subjects, but each subject, who have markedly different heart rates, exhibited different motion magnitudes. Fig. 5 depicts reduced brain motion for a subject with MCI and positive amyloid PET compared with a healthy control.

Discussion

This work introduces a novel 3D quantitative-aMRI algorithm that quantifies sub-voxel pulsatile brain motion. Based on phantom simulations, the algorithm can quantify motion of ~0.005 of a pixel size (~6$$$\mu m$$$ in our acquisition protocol), with great robustness to noise. In-vivo analysis showed that 3D q-aMRI successfully quantifies the 3D aMRI signal; this is repeatable and reproducible in two subjects. The heart rate of Subject-1 (91-BPM) was greater compared with subject-2 (61-BPM), which might explain the differences in motion magnitudes. Finally, preliminary data of applying 3D q-aMRI to subjects with positive/negative amyloid PET is shown. We posit that the small reduction in heart rate seen in the negative case is unlikely to explain the significant differences in brain motion, however this will have to be tested on a large cohort to understand confounders such as heart rate and other physiological variables.Conclusion

A novel 3D q-aMRI algorithm was introduced to quantifies sub-voxel pulsatile brain motion. Preliminary data shows the potential of 3D q-aMRI assessing abnormal biomechanics in patients with Alzheimer`s disease.Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowship and under Grant No. 1828993; NIH R01MH116173; R01EB019437; U01EB025162; P41EB030006; The Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund, NIH (R21NS111415), the Kānoa - Regional Economic Development & Investment Unit, New Zealand; We are grateful to Mātai Ngā Māngai Māori and to our research participants for dedicating their time toward this study. We would like to acknowledge the support of GE Healthcare. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.References

1. Holdsworth SJ, Rahimi MS, Ni WW, Zaharchuk G, Moseley ME. Amplified magnetic resonance imaging (aMRI). Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2016;75:2245–2254 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26142.

2.Terem I, Ni WW, Goubran M, et al. Revealing sub-voxel motions of brain tissue using phase-based amplified MRI (aMRI). Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2018;80:2549–2559 doi: 10.1002/mrm.27236.

3. Terem I, Dang L, Champagne A, et al. 3D amplified MRI (aMRI). Magn. Reson. Med. 2021;86:1674–1686.

4. Abderezaei J, Pionteck A, Terem I, et al. Development, calibration, and testing of 3D amplified MRI (aMRI) for the quantification of intrinsic brain motion. Brain Multiphysics 2021;2:100022 doi: 10.1016/j.brain.2021.100022.

5. Abderezaei J, Pionteck A, et al. Increased Hindbrain Motion in Chiari Malformation I Patients Measured Through 3D Amplified MRI (3D aMRI). medRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.25.22281481 (2022).

6. Abderezaei J, Martinez J, Terem I, et al. Amplified Flow Imaging (aFlow): A Novel MRI-Based Tool to Unravel the Coupled Dynamics Between the Human Brain and Cerebrovasculature. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020;39:4113–4123.

7. Kumar H, Terem I, Kurt M, Kwon E, Holdsworth SJ, Amplified MRI and Physiological Brain Tissue Motion. In Motion Correction in MRI. Ed: J.B Andre & A. Van der Kouwe, Elsevier. 2022.

8. Champagne AA, Peponoulas E, Terem I, et al. Novel strain analysis informs about injury susceptibility of the corpus callosum to repeated impacts. Brain Commun 2019;1:fcz021.

9. Mathewson J, Hale D. Detection of channels in seismic images using the steerable pyramid. SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts. 2008:859-863.

10. Luche CAD, Delle Luche CA, Denis F, Baskurt A. 3D steerable pyramid based on conic filters. Wavelet Applications in Industrial Processing. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.516184.

11. DJ Fleet, AD Jepson. Computation of component image velocity from local phase information. Int J Computer Vision 5, 77-104(1990).

12. Wadhwa N, Chen JG, Sellon JB, Wei D, Rubinstein M, Ghaffari R, Freeman DM, Büyüköztürk O, Wang P, Sun S, Kang SH, Bertoldi K, Durand F, Freeman WT. Motion microscopy for visualizing and quantifying small motions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Oct 31;114(44):11639-11644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1703715114. Epub 2017 Oct 16. PMID: 29078275; PMCID: PMC5676878.

13. Davis A, Bouman KL, Chen JG, Rubinstein M, Durand F, and Freeman DM. Visual vibrometry: Estimating material properties from small motion in video. In IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol, 39, no. 4, pp. 732-745, 1 April 2017.

14. Feng BT, Ogren AC, Dario C, and Bouman K L. "Visual Vibration Tomography: Estimating Interior Material Properties from Monocular Video." CVPR, 2022.

Figures

Figure 4: The pulsatile brain motion for two subjects in the sagittal (S/I direction, white arrows) at two different days ($$$t_{0}$$$ and $$$t_{1}$$$) and their corresponding heart rates (HR), showing high repeatability across the time points within each subject, and similar motion patterns with different magnitudes across the two subjects who in this case have large differences in heart rates.