1170

Federated MRI Reconstruction with Deep Generative Models1Department Electrical and Electronics Engineering, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey, 2National Magnetic Resonance Research Center (UMRAM), Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey, 3Aysel Sabuncu Brain Research Center, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence

Generalization performance in learning-based MRI reconstruction relies on comprehensive model training on large, diverse datasets collected at multiple institutions. Yet, centralized training after cross-site transfer of imaging data introduces patient privacy risks. Federated learning (FL) is a promising framework that enables collaborative training without explicit data sharing across sites. Here, we introduce a novel FL method for MRI reconstruction based on a multi-site deep generative model. To improve performance and reliability against data heterogeneity across sites, the proposed method decentrally trains a generative image prior decoupled from the imaging operator, and adapts it to minimize data-consistency loss during inference.Introduction

MRI is ubiquitous in clinical applications with its unparalleled tissue contrast, yet its undesirably long scan times necessitate adoption of acceleration techniques1,2. In recent years, deep-learning models have become the gold standard in reconstruction of accelerated MRI acquisitions3-13. As these models poorly represent features scarcely present in the training set, generalization requires training on a diverse collection of MRI data from multiple sites, which raises privacy concerns related to data transfer14. Aiming at privacy concerns, federated learning (FL) is a promising framework that collaboratively trains a multi-site model without sharing local data15-17. A multi-site model can improve generalization particularly in sites with relatively limited or uniform training data. At the same time, a naive multi-site model can show suboptimal sensitivity to site-specific features due to cross-site heterogeneity in the data distribution18. Recent FL methods for MRI reconstruction are based on non-adaptive conditional models that generalize poorly against variability in the data distribution and the imaging operator that captures the influence of k-space sampling density19. As such, previous methods attempt to mitigate potential performance losses by prescribing matched imaging operators across sites and across training-test sets, reducing flexibility. Here, we introduce a novel FL method for MRI reconstruction, FedGIMP, that decentrally trains a generative MRI prior decoupled from the imaging operator to improve patient privacy and flexibility in multi-site collaborations. We operationalize the prior as an unconditional adversarial model with a cross-site-shared generator to capture site-general representations, albeit with site-specific latents to maintain specificity in synthesized MR images. We leverage prior adaptation to further enhance specificity of the multi-site model and improve reliability against domain shifts across sites and across training-test sets.Methods

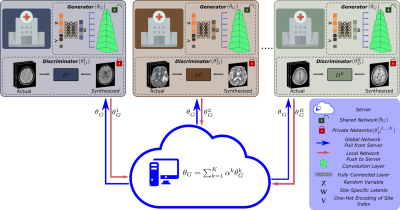

Generative model: FedGIMP leverages a multi-site generative model to capture the distribution of high-quality MR images (Fig. 1). A shared generator (θG) is used to capture site-general representations, and K local discriminators (θD1,..,K) are retained to minimize communication costs. (θG) includes a mapper (θM) that receives a site index (v) to produce site-specific latent variables (ω), and a synthesizer (θS) that generates images given a random latent (z):$$$\hat{x}=G_{\theta_G}(z \oplus v) = S_{\theta_S}(M_{\theta_M}(z \oplus v))$$$

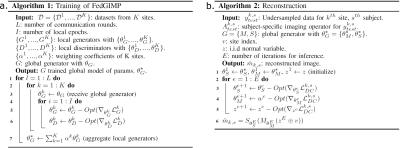

Federated training: When the FL training starts, a global generator along with K local copies and local discriminators are randomly initialized. In each communication round, the FL server broadcasts the global generator to the sites. The local generator copies are locally trained, and resent to the server for model aggregation via federated averaging (Fig. 2).

Reconstruction: The subject-specific imaging operator at a test site (Ak,s for site k, subject s) is first injected to the trained generative model. In particular, images synthesized by the model are projected onto individual coils, and undersampled in k-space with the sampling mask of the subject. An inference optimization is then conducted to adapt the generative model to the reconstruction task (Fig. 2). Model parameters are updated to minimize data-consistency loss between synthesized and acquired k-space data ytestk,s:

$$$L^{k,s}_{DC}=\left\|A^{k,s}_{test}S_{\theta_S}(M_{\theta_M}(z \oplus v))-y^{k,s}_{test}\right\|_{2}$$$

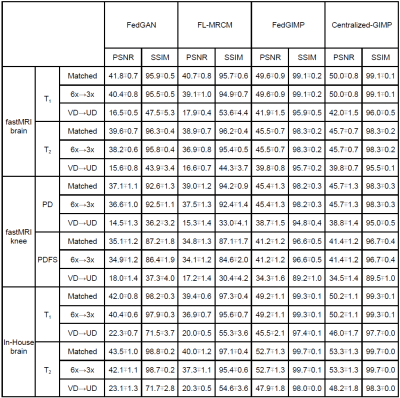

Analyses: Multi-coil acquisitions from fastMRI brain20; fastMRI knee20; in-house brain12; and Calgary-Campinas brain21 datasets were analyzed. Cross-validation was performed with a (60%,10%,30%) split of (training,validation,test) subjects. Data were retrospectively undersampled at R=3x, 6x acceleration rates via either variable (VD) or uniform (UD) sampling density. Training and inference was performed via the Adam optimizer with 100 communication rounds, 1 training epoch/round, 1200 inference iterations, and a 0.01 learning rate. FedGIMP was compared with a centralized benchmark GIMP (based on the same architecture as FedGIMP), and state-of-the-art methods FedGAN22 and FL-MRCM19. Code for FedGIMP is available at https://github.com/icon-lab/FedGIMP.

Results

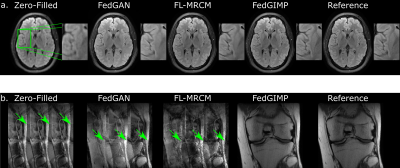

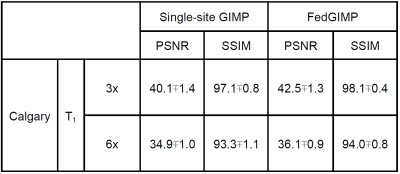

Fig. 3 lists performance metrics for competing methods while the acceleration rate (R) and sampling density (SD) were matched, R was mismatched, and SD was mismatched between the training-test sets. Representative images are displayed in Fig. 4. Overall, FedGIMP outperforms the closest contender by 7.1 dB PSNR, 3.4 % in SSIM under matched R-SD, by 8.4 dB PSNR, 4.1 % in SSIM under mismatched R, by 22.5 dB PSNR, 42.7 % in SSIM under mismatched SD. Meanwhile, it yields on par performance with the centralized benchmark.Fig. 5 demonstrates the benefit of a multi-site model over a single-site model for a site with limited access to training data. For this purpose, a fourth site with relatively limited training data was included in the FL process for FedGIMP. FedGIMP outperforms the single-site model for the added site by 3.6 dB PSNR and 1.7 % SSIM.

Discussion

Here we introduced a novel federated learning method for MRI reconstruction based on a generative adversarial model. FedGIMP decentrally trains a multi-site MRI prior with a site-index for maintaining site specificity, and adapts its prior for the reconstruction task in individual sites by embedding the imaging operator during inference.Conclusion

Our novel decoupled FL approach improves reliability against data heterogeneity across sites, and improves performance in sites with scarce training data. Therefore, FedGIMP holds great promise for improving multi-institutional collaborations in learning-based MRI reconstruction.Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by a TUBA GEBIP 2015 fellowship, a BAGEP 2017 fellowship, and a TUBITAK 121E488 grant.References

1. M. Lustig, D. Donoho, and J. M. Pauly, “Sparse MRI: The application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 58, no. 6, pp. 1182–1195, 2007.

2. T. M. Quan, T. Nguyen-Duc, and W.-K. Jeong, “Compressed sensing MRI reconstruction with cyclic loss in generative adversarial networks,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 1488–1497, 2018.

3. B. Yaman, S. A. H. Hosseini, S. Moeller, J. Ellermann, K. Uğurbil, and M. Akçakaya, “Self-supervised learning of physics-guided reconstruction neural networks without fully sampled reference data,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 84, no. 6, pp. 3172–3191, 2020.

4. J. I. Tamir, S. X. Yu, and M. Lustig, “Unsupervised deep basis pursuit: Learning reconstruction without ground-truth data,” in Proceedings of ISMRM, 2019, p. 0660.

5. H. K. Aggarwal, M. P. Mani, and M. Jacob, “MoDL: Model-Based Deep Learning Architecture for Inverse Problems,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 394–405, 2019.

6. J. Schlemper, J. Caballero, J. V. Hajnal, A. Price, and D. Rueckert, “A Deep Cascade of Convolutional Neural Networks for MR Image Reconstruction,” in Inf Process Med Imaging, 2017, pp. 647–658.

7. D. Liang, J. Cheng, Z. Ke, and L. Ying, “Deep magnetic resonance image reconstruction: Inverse problems meet neural networks,” IEEE Signal Process Mag, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 141–151, 2020.

8. K. C. Tezcan, C. F. Baumgartner, R. Luechinger, K. P. Pruessmann, and E. Konukoglu, “MR Image Reconstruction Using Deep Density Priors,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 1633–1642, 2019.

9. M. Mardani, E. Gong, J. Y. Cheng, S. S. Vasanawala, G. Zaharchuk, L. Xing, and J. M. Pauly, “Deep Generative Adversarial Neural Networks for Compressive Sensing (GANCS) MRI,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, pp. 1–1, Jul. 2018.

10. G. Oh, B. Sim, H. Chung, L. Sunwoo, and J. C. Ye, “Unpaired Deep Learning for Accelerated MRI Using Optimal Transport Driven CycleGAN,” IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging, vol. 6, pp. 1285–1296, 2020.

11. K. Lei, M. Mardani, J. M. Pauly, and S. S. Vasanawala, “Wasserstein GANs for MR Imaging: From Paired to Unpaired Training,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 105–115, 2021

12. S. U. H. Dar, M. Yurt, M. Shahdloo, M. E. Ildiz, B. Tinaz, and T. Cukur, “Prior-Guided Image Reconstruction for Accelerated Multi-Contrast MRI via Generative Adversarial Networks,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 1072–1087, Oct. 2020.

13. K. Hammernik, T. Klatzer, E. Kobler, M. P. Recht, D. K. Sodickson, T. Pock, and F. Knoll, “Learning a variational network for reconstruction of accelerated MRI data,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 79, no. 6, pp. 3055–3071, Jun. 2018.

14. G. A. Kaissis, M. R. Makowski, D. Rückert, and R. F. Braren, “Secure, privacy-preserving and federated machine learning in medical imaging,” Nature Machine Intelligence, vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 305–311, Jun. 2020.

15. N. Rieke, J. Hancox, W. Li, F. Milletar`ı, H. R. Roth, S. Albarqouni, S. Bakas et al., “The future of digital health with federated learning,” NPJ Digit Med, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 119, 2020.

16. Q. Liu, C. Chen, J. Qin, Q. Dou, and P. Heng, “Feddg: Federated domain generalization on medical image segmentation via episodic learning in continuous frequency space,” in Comput Vis Pattern Recognit, 2021, pp.1013–1023.

17. H. R. Roth, K. Chang, P. Singh, N. Neumark, W. Li, V. Gupta, S. Gupta et al., “Federated Learning for Breast Density Classification: A Real-World Implementation,” in Dom Adapt Rep Trans, 2020, p. 181–191.

18. X. Li, Y. Gu, N. Dvornek, L. H. Staib, P. Ventola, and J. S. Duncan, “Multi-site fmri analysis using privacy-preserving federated learning and domain adaptation: Abide results,” Med Image Anal, vol. 65, p. 101765, 2020.

19. P. Guo, P. Wang, J. Zhou, S. Jiang, and V. M. Patel, “Multi-institutional Collaborations for Improving Deep Learning-based Magnetic Resonance Image Reconstruction Using Federated Learning,” arXiv:2103.02148, 2021.

20. F. Knoll, J. Zbontar, A. Sriram, M. J. Muckley, M. Bruno, A. Defazio, M. Parente et al., “fastMRI: A publicly available raw k-space and DICOM dataset of knee images for accelerated MR image reconstruction using machine learning,” Rad Artif Intell, vol. 2, no. 1, p. e190007, 2020.

21. R. Souza, O. Lucena, J. Garrafa, D. Gobbi, M. Saluzzi, S. Appenzeller, L. Rittner, R. Frayne, R. Lotufo, An open, multi-vendor, multi-field strength brain MR dataset and analysis of publicly available skull stripping methods agreement, NeuroImage 170 (2018) 482–494.

22. M. Rasouli, T. Sun, and R. Rajagopal, “Fedgan: Federated generative adversarial networks for distributed data,” arXiv:2006.07228, 2020.Figures