1165

A novel deep learning method for automated identification of the retinogeniculate pathway using dMRI tractography

Sipei Li1,2, Jianzhong He2,3, Tengfei Xue2,4, Guoqiang Xie2,5, Shun Yao2,6, Yuqian Chen2,4, Erickson F. Torio2, Yuanjing Feng3, Dhiego CA Bastos2, Yogesh Rathi2, Nikos Makris2,7, Ron Kikinis2, Wenya Linda Bi2, Alexandra J Golby2, Lauren J O’Donnell2, and Fan Zhang2

1University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China, 2Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 3Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China, 4University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 5Nuclear Industry 215 Hospital of Shaanxi Province, Xianyang, China, 6The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China, 7Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

1University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China, 2Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 3Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China, 4University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 5Nuclear Industry 215 Hospital of Shaanxi Province, Xianyang, China, 6The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China, 7Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Nerves, Brain

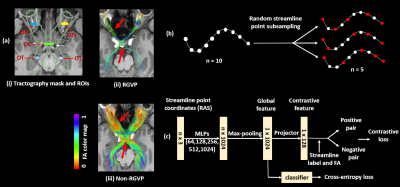

We present a novel deep learning framework, DeepRGVP, for the retinogeniculate pathway (RGVP) identification from dMRI tractography data. We propose a novel microstructure-supervised contrastive learning method (MicroSCL) that leverages both streamline labels and tissue microstructure (fractional anisotropy) for RGVP and non-RGVP. We propose a simple and effective streamline-level data augmentation method (StreamDA) to address highly imbalanced training data. We perform comparisons with three state-of-the-art methods on an RGVP dataset. Experimental results show that DeepRGVP has superior RGVP identification performance.INTRODUCTION

The retinogeniculate pathway (RGVP) is responsible for carrying visual information from the retina to the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN)1,2. Diffusion MRI (dMRI) tractography is an advanced imaging method3 that has shown successful RGVP mapping for clinical and research purposes4–8. Current method for RGVP identification from tractography relies on manual selection9; however, it is time-consuming and inefficient with high clinical and expert labor costs. Hence, there is a high need for computational methods to enable automated RGVP identification.Recent advances in deep learning provide a promising approach to enable accurate and fast identification of the RGVP. However, there are two key challenges. First, current tractography parcellation methods for white matter tract parcellation are based on streamline geometric features10–13. However, this can be ineffective to differentiate RGVP and non-RGVP streamlines because of their small geometric differences (see Fig-1(a)). Second, tractography data can have a highly imbalanced streamline sample distribution between RGVP and non-RGVP streamlines (our data shows a ratio of 1:8). This would limit network generalization for small-size sample categories14.

In this study, we present a novel deep learning approach, namely DeepRGVP, that enables fast and accurate RGVP identification using dMRI tractography. DeepRGVP is based on Superficial White Matter Analysis (SupWMA)12, a point-cloud-based network15 with supervised contrastive learning (SCL)16, which is designed for classification of superficial white matter streamlines. DeepRGVP extends SupWMA with two innovative additions: 1) a microstructure-informed SCL (MicroSCL) method that leverages both streamline label (RGVP and non-RGVP) and tissue microstructure information (fractional anisotropy; FA) to determine positive and negative pairs, and 2) a simple and successful streamline-level data augmentation (StreamDA) method to address the imbalanced training data problem.

METHODS

Our overall goal is to identify streamlines that belong to the RGVP from input tractography data, as overviewed in Figure 1. There are two main components, including a SCL subnetwork to learn the global feature for each input streamline, and a downstream subnetwork to classify the streamlines into RGVP and non-RGVP.Microstructure-informed supervised contrastive learning: In addition to the traditional usage of label information (RGVP and non-RGVP) for positive and negative sample pair determination16, we include FA information by constraining positive pairs to satisfy $$$ΔFA = {\left| FA_i - FA_p\right|} < T_{FA}$$$, where TFA is a threshold on the allowable mean streamline FA difference between streamlines in a positive pair. Overall, the contrastive loss LMicroSCL used is:

$$L_{MicroSCL} = \sum_{i \in I}\frac{-1}{\left| P(i)\right|}\sum_{i \in P(i)} log \frac{exp(z_i \cdot z_p /\tau)}{\sum_{i \in A(i)}{exp(z_i \cdot z_a /\tau)}}\\=\sum_{i \in I}\frac{-1}{\left| M(i) \cap N(i)\right|}\sum_{i \in M(i) \cap N(i)} log \frac{exp(z_i \cdot z_{m \cap n} /\tau)}{\sum_{i \in A(i)}{exp(z_i \cdot z_{a} /\tau)}}$$

where i is a streamline belonging to a training batch I; M(i) is the streamline set of the same class label as streamline i; N(i) is the streamline set that satisfies the ΔFA condition; P(i) is the intersection of M(i) and N(i); A(i) is the set that includes all streamlines except for streamline i in batch I; zi, zp and za are contrastive features of streamlines i, p ∈ P(i) and a ∈ A(i), respectively; τ (temperature) is a hyperparameter for optimization predefined to be 0.1 as suggested17.

Streamline-level data augmentation: To obtain a balanced training dataset, StreamDA is applied to generate additional samples. Each streamline consists of a sequence of points estimated by a tractography algorithm. For input to the network, we represent each streamline using P points sampled along the streamline. For DA, we generate additional samples from each streamline by repeating the streamline point subsampling process multiple times, such that each time a different point subset is generated (as demonstrated in Figure1(b)). We note that StreamDA is different from common DA strategies, such as data repetition and adding noise, where additional samples are synthetically generated.

EXPERIMENTS

We use a total of 62 dMRI datasets from the Human Connectome Project (HCP)18 database, in which 40 are used for model training, 10 for validation, and 12 for testing. Ground truth RGVP data are generated as described in our previous work1. We compare DeepRGVP to three SOTA methods, including DeepWMA19, DCNN13 and SupWMA12. We also performed an ablation study to evaluate the effects of MicroSCL and StreamDA, with other four comparisons. Evaluation metrics including precision, recall, F1 and classification accuracy are used.RESULTS

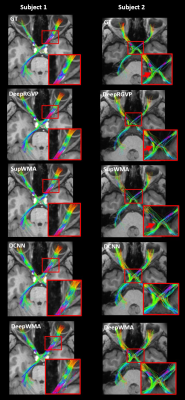

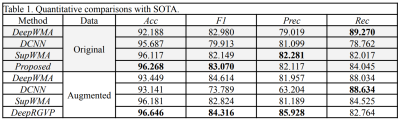

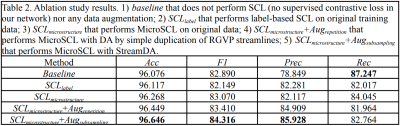

Table 1 demonstrates that DeepRGVP generates the highest accuracy and F1 using both original and augmented data, demonstrating the advantage of the MicroSCL method. In addition, DeepRGVP generates relatively high scores for both the precision and recall, demonstrating balanced classification performance between RGVP and non-RGVP streamlines. Figure 2 gives a visual comparison of the RGVP identified from each method using its best performing model. DCNN and DeepWMA are visually overinclusive with more streamlines compared to the ground truth. DeepRGVP and SupWMA are visually similar to GT. But DeepRGVP has improved sensitivity in identifying local structures. Table 2 gives the ablation study results, showing the proposed method generates the best performance.CONCLUSION & DISCUSSION

We present a novel contrastive learning framework to enable automated RGVP identification. We propose a streamline-level subsampling strategy as an effective data augmentation strategy for imbalanced training data. Overall, our study shows the high potential of using deep learning to automatically identify the RGVP.Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the following NIH grants: P41EB015902, R01MH074794, R01MH125860 and R01MH119222. F.Z. also acknowledges a BWH Radiology Research Pilot Grant Award.References

1. He, J. & etal. Comparison of multiple tractography methods for reconstruction of the retinogeniculate visual pathway using diffusion MRI. Human Brain Mapping 42, 3887–3904 (2021).2. Chacko, L. W. The laminar pattern of the lateral geniculate body in the primates. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 11, 211–224 (1948).

3. Basser, P. & etal. In vivo fiber tractography using DT‐MRI data. Magnetic resonance 44, 625–632 (2000).

4. Hofer, S. & etal. Reconstruction and dissection of the entire human visual pathway using diffusion tensor MRI. Front. Neuroanat. 4, 15 (2010).

5. Yoshino, M. & etal. Visualization of Cranial Nerves Using High-Definition Fiber Tractography. Neurosurgery 79, 146–165 (2016).

6. Altıntaş, Ö. & etal. Correlation of the measurements of optical coherence tomography and diffuse tension imaging of optic pathways in amblyopia. Int. Ophthalmol. 37, 85–93 (2017).

7. Ather, S. & etal. Aberrant visual pathway development in albinism: From retina to cortex. Hum. Brain Mapp. 40, 777–788 (2019).

8. Panesar, S. S. & etal. Tractography for Surgical Neuro-Oncology Planning: Towards a Gold Standard. Neurotherapeutics 16, 36–51 (2019).

9. Oishi, K. & etal. Human brain white matter atlas: identification and assignment of common anatomical structures in superficial white matter. Neuroimage 43, 447–457 (2008).

10. Gupta, V. & etal. FiberNET: An Ensemble Deep Learning Framework for Clustering White Matter Fibers. in MICCAI 2017 548–555.

11. Ngattai Lam, P. D. & etal. TRAFIC: Fiber Tract Classification Using Deep Learning. SPIE 10574, (2018).

12. Xue, T. & etal. SupWMA: Consistent and Efficient Tractography Parcellation of Superficial White Matter with Deep Learning. in ISBI 1–5 (2022).

13. Xu, H. & etal. Objective Detection of Eloquent Axonal Pathways to Minimize Postoperative Deficits in Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery using Diffusion Tractography and Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 1910–1922 (2019).

14. Johnson, J. M. & etal. Survey on deep learning with class imbalance. Journal of Big Data 6, 1–54 (2019).

15. Charles, Q. & etal. PointNet: Deep Learning on Point Sets for 3D Classification and Segmentation. in CVPR 652–660 (2017).

16. Khosla, P. & etal. Supervised Contrastive Learning. (2020).

17. Chen, T. & etal. A Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations. in PMLR vol. 119 1597–1607 (2020).

18. Van Essen, D. C. & etal. The WU-Minn Human Connectome Project: an overview. Neuroimage 80, 62–79 (2013).

19. Zhang, F. & etal. Deep white matter analysis (DeepWMA): Fast and consistent tractography segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 65, 101761 (2020).

20. Norton, I. & etal. SlicerDMRI: Open Source Diffusion MRI Software for Brain Cancer Research. Cancer Res. 77, e101–e103 (2017).

21. Zhang, F. & etal. SlicerDMRI: Diffusion MRI and Tractography Research Software for Brain Cancer Surgery Planning and Visualization. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 4, 299–309 (2020).

Figures

Figure 1. Method overview. (a) shows visualization of example input tractography data, RGVP streamlines selected using expert-drawn ROIs, and all other unselected streamlines (non-RGVP). (b) shows the proposed StreamDA method to resolve potential training biases for the imbalanced input data. Additional samples are generated to get a balanced training dataset. (c) shows the overall network architecture that includes a Supervised Contrastive Learning subnetwork to learn the global feature and a downstream subnetwork to classify the streamlines into RGVP and non-RGVP.

Figure 2. Visual comparison of the identified RGVPs in two example subjects using their best performing model. The inset images are provided for better visualization of local RGVP regions. DCNN and DeepWMA are visually overinclusive with more streamlines compared to GT. DeepRGVP and SupWMA are visually similar to GT. But DeepRGVP has improved sensitivity in identifying local structures, e.g., the ipsilateral pathway passing through the optic chiasm in Subject 2 (indicated by the red arrows).

Table 1. Quantitative comparisons with SOTA.

Table 2. Ablation study results. 1) baseline that does not perform SCL (no supervised contrastive loss in our network) nor any data augmentation; 2) SCLlabel that performs label-based SCL on original training data; 3) SCLlabel+macro that performs MicroSCL on original data; 4) SCLlabel+macro+Augrepetition that performs MicroSCL with DA by simple duplication of RGVP streamlines; 5) SCLlabel+macro+Augsubsampling that performs MicroSCL with StreamDA.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1165