1162

Segmented 3D GRE-EPI optimized for BOLD fMRI at 9.4T1High-field Magnetic Resonance Center, Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics, Tuebingen, Germany, 2Department for Biomedical Magnetic Resonance, University Hospital Tuebingen, Tuebingen, Germany, 3German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), Bonn, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, fMRI

A segmented 3D GRE EPI was adapted and optimized specifically for BOLD fMRI at a 9.4T MR system. While EPI is widely used in fMRI, especially at UHF its application becomes challenging for instance for long echo trains used at high spatial resolution. In this work, investigations on the stability of the system, tSNR, flexible sequence design, different temporal phase correction schemes, and efficient use of the limited SAR budget were performed. Finally, a protocol for BOLD fMRI of the motor cortex at 1.0mm nominal isotropic resolution (FOV=200x215x44mm³) with a volume TR of 3 seconds was set up.Introduction

Functional imaging requires the acquisition of MR data with high spatiotemporal resolution, and echo planar imaging (EPI) is widely used for these applications. Still, especially at ultra-high field strength (UHF) inhomogeneity of the static magnetic field, phase instability, SAR limitations and other issues make its application challenging. While in principle shorter T2* at UHF1 is beneficial for BOLD imaging, the same effect is disadvantageous for the use of high-resolution gradient echo EPI because of increased blurring in rather long echo trains. To that end, we investigate stability and quality of segmented 3D GRE EPI at 9.4T by adapting and modifying a sequence that was previously already used at 3T2,3, 7T4 and 9.4T5 specifically for BOLD imaging. As a first benchmark, the aim was to enable imaging of the motorcortex at 1mm nominal isotropic resolution within a volume TR (TRvol) of three seconds.Methods

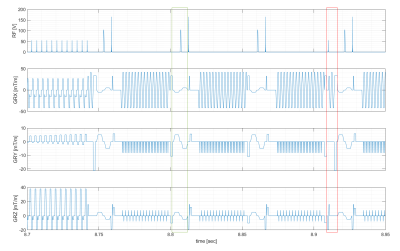

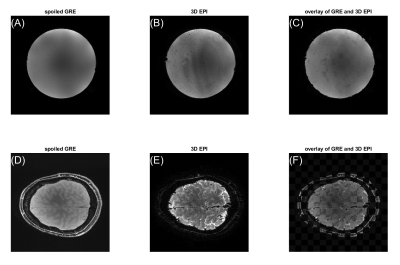

Data were acquired at a human 9.4T MR scanner (Siemens, Germany) in healthy subjects meeting the local ethics committee’s requirements. A custom build 16Tx/31Rx head coil6 was used in combination with a whole-body gradient system with limited performance (70mT/m|200T/m/s) compared to the head gradient system used in5. The skipped-CAIPI 3D GRE EPI sequence3 allows to segment a single-shot trajectory in k-space (with or without CAIPI blips), further into multiple ‘shots’ rather than having a single excitation RF pulse for a 2D partition of k-space. This subset of shots is denoted here as ‘blades’. Segmentation comes at the cost of additional excitation pulses and potentially higher SAR, if shot-to-shot TR is reduced, compared to single shot EPI. On the other hand, it enables shorter echo train lengths (25-35ms for a matrix of 250x250x44) which is necessary to account for the short T2* at 9.4T and stronger susceptibility effects. Geometric distortions were compared to an RF and gradient spoiled GRE sequence at the same matrix size and spatial resolution. Still, EPI had undersampling factor (US) four (two protocols: CAIPIRINHA=2x2z1, or GRAPPA=1x4, both: TE=18ms), in contrast to US=2, for the spoiled GRE.The EPI protocols begin with a 32x32 lines reference scan for GRAPPA reconstruction. Next, an external phase navigator is acquired (FA=5°), followed by optional fat saturation before the image acquisition. For consecutive readout pulses (sinc shaped, tp=660µs, BWTP=17, FA=10°) phase navigator and fat saturation can be applied flexible per ‘shot’, ‘blade’ or ‘volume’, to efficiently use the available SAR. A representative sequence diagram is shown in Figure 1. MR data were reconstructed including phase correction, GRAPPA-reconstruction and adaptive coil combination7. If not stated differently, in vivo data were corrected for motion retrospectively (rigid transformations; mutual information based using elastix8). Evaluation of BOLD effect in functional data was performed in LISA9 to avoid spatial smoothing and maintain the spatial resolution.

Results

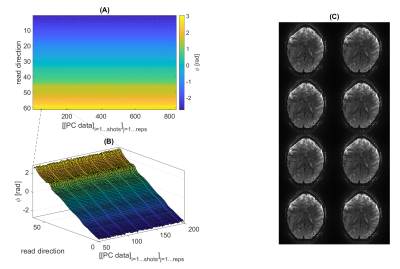

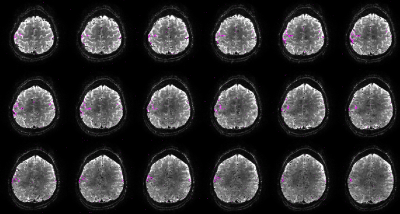

The phase navigator data were found to be sufficiently stable to only acquire phase calibration lines once per volume, which saves both time and SAR, as shown in Figure 2. Even retrospective shuffling around ‘shots’ across different volumes after phase correction yielded visibly not affected images (Figure 2). Geometric distortions were mild, as shown in Figure 3 for 0.8mm³ isotropic resolution both in vivo and in a spherical agar phantom. As a lower limit for the minimal possible observable effect size, tSNR can be considered. The spatial median within the inner 40/44 slices was found to be around 20 in vivo and 97 in the phantom (matrix=200x200x44 , TRvol=3.2s; nominal 1.0mm³; 110/115 frames; for nominal 0.8mm³, matrix=250x250x44: 13.5 and 50 respectively at TRvol=3.6s). These numbers indicate that tSNR is limited by physiological noise10 rather than system instability or thermal noise. Further optimizations and adaptions of the sequence were performed regarding: fat saturation (FA, pulse type/duration, spoiler gradients) and duration of the excitation RF pulse (data not shown). The result of a functional scan is shown in Figure 4. Here, the matrix size was slightly reduced to 44x200x215 (HF-LR-AP) at 1.0mm isotropic resolution resulting in TRvol=3s.Discussion

The presented findings show that the application of segmented 3D GRE EPI is plausible for BOLD fMRI at UHF. Phase correction is possible based on a single set of calibration data per TRvol because of high temporal stability. Geometric distortions are mild and the tSNR of 13.5 at 0.8mm³ in this work is close to the tSNR of 18±4 mentioned in5 where smaller matrix=44x132x10 and 60% larger voxels were used. The volume TR might not yet be short enough compared to e.g. the respiratory cycle, but could for instance be traded against a smaller matrix size or higher undersampling. Future developments will include the application of true pTx pulses to compensate B1+ inhomogeneity and RF preparation to increase GM/WM contrast for automatic tissue segmentation on the functional images, e.g. with binomial pulses10, off-resonant saturation or saturation recovery pulses.Conclusion

The feasibility of segmented 3D GRE EPI for BOLD fRMI at 9.4T was investigated. As a first test, with the flexibly adjustable sequence a protocol with tSNR=20 was set up for BOLD fMRI in the motorcortex at 1.0mm³ nominal resolution at TRvol=3s. This further extends possible applications of the sequence and makes it a useful tool for BOLD fMRI at various field strengths.Acknowledgements

The financial support of Max Planck Society, German Research Foundation (Reinhart Koselleck project DFG SCHE658/12 and ZA 814/7-1) and ERC Advanced Grant, No 834940 is gratefully acknowledged.References

1 Zhu, J., Klarhöfer, M., Santini, F., Scheffler, K., & Bieri, O. (2014). Relaxation Measurements in Brain Tissue at Field Strengths Between 0.35T and 9.4T. Poster presented at Joint Annual Meeting ISMRM-ESMRMB 2014, Milano, Italy.

2 R. Stirnberg, W. Huijbers, D. Brenner, et al., Rapid whole-brain resting-state fMRI at 3T: Efficiency-optimized three-dimensional EPI versus repetition time-matched simultaneous-multi-slice EPI, NeuroImage, Volume 163, 2017, Pages 81-92, ISSN 1053-8119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.08.031.

3 Stirnberg R, Stöcker T. Segmented K-space blipped-controlled aliasing in parallel imaging for high spatiotemporal resolution echo EPI. Magn Reson Med. 2020;00:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.28486

4 Le Ster C, Moreno A, Mauconduit F, et al., Comparison of SMS-EPI and 3D-EPI at 7T in an fMRI localizer study with matched spatiotemporal resolution and homogenized excitation profiles., 2019, PLoS ONE 14(11): e0225286. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal

5 Huber L., Tse D. H.Y., Wiggins C. J., Uludağ K., et al., Ultra-high resolution blood volume fMRI and BOLD fMRI in humans at 9.4 T: Capabilities and challenges, NeuroImage, Volume 178, 2018, Pages 769-779, ISSN 1053-8119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.06.025.

6 Shajan G., Kozlov M., Hoffmann J., Turner R., Scheffler K., & Pohmann R. A 16-channel dual-row transmit array in combination with a 31-element receive array for human brain imaging at 9.4 T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2013;71(2):870–879. doi:10.1002/mrm.24726

7 Walsh, D.O., Gmitro, A.F. and Marcellin, M.W. (2000), Adaptive reconstruction of phased array MR imagery. Magn. Reson. Med., 43: 682-690. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1522-2594(200005)43:5

8 S. Klein, M. Staring, K. Murphy, M. A. Viergever and J. P. W. Pluim, elastix: A Toolbox for Intensity-Based Medical Image Registration, IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 196-205, Jan. 2010, doi: 10.1109/TMI.2009.2035616.

9 Lohmann, G., Stelzer, J., Lacosse, E. et al., LISA improves statistical analysis for fMRI. Nat Commun 9, 4014 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06304-z

10 C. Triantafyllou, R.D. Hoge, G. Krueger, et al., Comparison of physiological noise at 1.5 T, 3 T and 7 T and optimization of fMRI acquisition parameters, NeuroImage, Volume 26, Issue 1, 2005, Pages 243-250, ISSN 1053-8119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.007.

11 Yuhui Chai, Linqing Li, Yicun Wang, et al., Magnetization transfer weighted EPI facilitates cortical depth determination in native fMRI space, NeuroImage, Volume 242, 2021, 118455, ISSN 1053-8119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118455.

Figures