1160

Distortionless, free-breathing, and respiratory resolved 3D diffusion weighted imaging of the abdomen1Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Bioengineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 3Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Pulse Sequence Design, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, abdomen, free-breathing

Abdominal imaging is frequently performed with uncomfortable breath holds, or respiratory triggering to reduce the effects of respiratory motion. Diffusion weighted sequences provide a useful clinical contrast but have prolonged scan times due to low SNR. These scans cannot be reliably completed in a single breath hold, and respiratory triggering has low scan efficiency. We present a respiratory resolved, diffusion-prepared 3D sequence that obtains distortionless diffusion weighted images during free-breathing. We describe techniques to address the myriad of challenges including: 3D shot-to-shot phase correction, respiratory binning, diffusion encoding during free-breathing, and robustness to off-resonance.Introduction

Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) is a desirable clinical contrast for treatment planning and cancer screening. Abdominal DWI is a challenge due to respiratory motion, long scan times, and off-resonance, which causes distortion in the widely used DW-EPI sequence. Respiratory triggering can reduce respiratory motion artifacts, but this is ineffective for irregular breathing patterns and depends on correct placement of the bellows. Breath-holds are not feasible for all patients. We present a tightly integrated sequence and reconstruction that obtains distortionless diffusion images under free-breathing. We describe techniques to address the myriad of challenges including: 3D shot-to-shot phase correction, respiratory binning, diffusion encoding during free-breathing, and robustness to off-resonance.Methods

Sampling trajectory: Non-Cartesian trajectories are commonly employed in abdomen imaging due to their robustness to motion artifacts. However, the sampling density of non-Cartesian trajectories is difficult to control near the k-space center. This poses a challenge for obtaining low-resolution 3D phase navigators required to correct varying phase from motion-sensitizing diffusion gradients. A Cartesian trajectory allows the sampling density and phase navigator resolution to be easily adjusted. The ky-kz trajectory for each shot has two stages. The first stage randomly samples inner k-space. These lines are reconstructed using parallel imaging and used for phase correction in a self-phase-navigated strategy1. The second stage samples outer k-space following a Variable Density Radial (VD-RAD) Cartesian ordering2. Cartesian sampling makes reconstruction tractable due to separability along the readout dimension. Naively storing zero-filled k-space with matrix size 256$$$\,×\,$$$256$$$\,×\,$$$32$$$\,×\,$$$24 coils$$$\,×\,$$$100 shots requires ~40GB of RAM.Image encoding$$$\,$$$/$$$\,$$$diffusion contrast: A twice-refocused, M1-nulled diffusion preparation was paired with Cartesian 3D RF-spoiled gradient echo (FLASH) for distortionless imaging. A stabilizer gradient along the slice direction before the tipup stores the same net magnitude regardless of the random phase. The gradient area of the stabilizer must be carefully chosen since motion smaller than the slice thickness between the stabilizer and echo adds constant phase. This affects extended readouts because later echoes will be phase offset relative to early echoes, reducing apparent resolution. We mitigate this by applying a stabilizer area only twice the maximum slice phase encode area. This creates ripple artifacts from partially rephased T1-recovered fat, which we reduce by applying an elliptical partial Fourier mask.

Respiratory motion: A 2D-EPI image is used for binning data into respiratory states. The respiratory signal was extracted from the first principal component of concatenated respiratory navigators3. This strategy requires that respiratory navigators have the same contrast. Since diffusion contrast varies between shots due to motion, the respiratory navigator is placed before diffusion preparation.

Image-based shot weighting: Because the degree of motion varies within the volume, diffusion gradients may annihilate signal in certain regions. Instead of discarding entire shots, we adopt an image-based per-shot weighting to deemphasize data overly corrupted by diffusion gradients4. The weighting is obtained from complex phase navigator images as the first right singular vector of local xyz-shots matrices, similar to Walsh coil estimation5. The weighting is a k-space convolution but is efficiently computed using zero-padded FFTs.

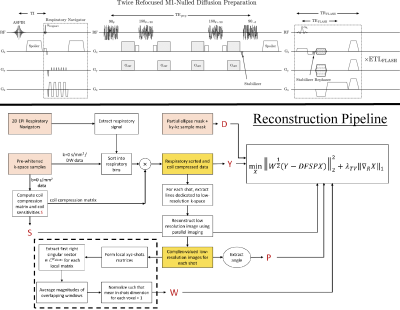

Reconstruction: The weighted least-squares with 1D-TV penalty along respiratory phases6 (Eq 1.) was solved with FISTA7. In Equation 1, W is the image-based per-shot weighting, Y-measured k-space, D-sampling, F-FFT, P-phase navigator, S-coil sensitivities, X-image for each respiratory phase. The 1D-TV proximal operator was solved with gradient descent. Figure 1 shows the sequence and reconstruction pipeline.$$\min_X ||W^{\frac{1}{2}}(Y-DFSPX)||_2^2+\lambda_{TV}||\nabla_RX||_1\,\,\,\,\,\,(\mathrm{Eq}\,1.)$$

Acquisition: Two healthy volunteers (one male, one female) were scanned on a 3T Signa Premier (GE Healthcare) following IRB approval and informed consent. Acquisition parameters for coronal free-breathing DW-FLASH were: 4 respiratory bins, respiratory navigator EPI-ETL 8 (readout S/I phase encode L/R), FLASH-TE/TR 1.4/3.5 ms, flip angle ramp 5-8°, matrix size 256$$$\,×\,$$$192$$$\,×\,$$$24, voxel size 1.4$$$\,×\,$$$1.9$$$\,×\,$$$5 mm, spine$$$\,$$$+$$$\,$$$AiR coil (GE Healthcare), diffusion axes L/R+A/P, ETL 90/40 lines randomly sample center 16$$$\,×\,$$$8 region, TEprep/TR 60/1600 ms, 140 shots, scan time 7:40 for b=0/500$$$\,$$$s/mm2, ASPIR fat suppression, stabilizer 2 and 4 cycles/cm. B1-insensitive optimal control pulses8 were used for preparation. Coil sensitivities were estimated from time-averaged b=0$$$\,$$$s/mm2 images using ESPIRIT9, SVD compressed from 56 to 24 channels, reconstruction ~25 minutes (2 NVIDIA Titan GPUs, 128 GB RAM). Respiratory-triggered 2-shot DW-EPI MUSE1 was acquired with identical FOV and 2 NEX, scan time 3:32, 6 slices/trigger, TE 55 ms, ASPIR.

Results

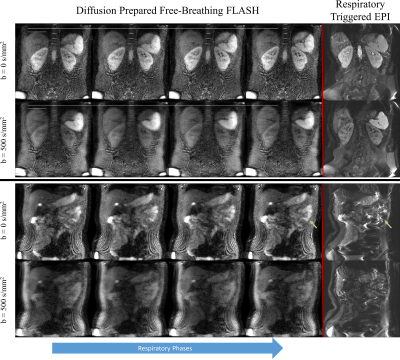

The effects of transient fat signal rephased during the readout is shown in the respiratory resolved images of Figure 2. Partial Fourier masking reduces these artifacts. Figure 3 shows the effect of high stabilizer area, which sensitizes the resolution to subvoxel motion. A smaller stabilizer area improves apparent resolution but introduces transient fat signal. Figure 4 shows a comparison with respiratory-triggered DW-EPI. Distortion in EPI is evident in the bowels and other organs. The proposed method is distortionless and has similar contrast. Figure 5 shows the benefit of shot weightings computed from phase navigators. Signal recovery is improved beneath the diaphragm, an area with high motion.Discussion

We have presented a distortionless free-breathing diffusion weighted sequence. Although M1-nulling is employed, the DW sequences do not recover all signal under the diaphragm. Future work includes verifying ADCs under free-breathing, interleaved fat saturation during readout, and prospective partial Fourier.Conclusion

Distortionless, volumetric, diffusion weighted images can be obtained during free-breathing.Acknowledgements

NIH R01-EB009055, NIH R01-CA249893, GE Healthcare, Karolinska Foundation for pulse programming assistance.References

1. Chen NK et al. A robust multi-shot scan strategy for high-resolution diffusion weighted MRI enabled by multiplexed sensitivity-encoding (MUSE). Neuroimage. 2013;72.

2. Cheng JY et al. Free-Breathing pediatric MRI with Nonrigid Motion Correction and Acceleration. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2015;42(2).

3. Zhang T et al. Robust self-navigated body MRI using dense coil arrays. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2016;76(1).

4. Miller KL and Pauly JM. Nonlinear phase correction for navigated diffusion imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2003;50(2).

5. Walsh DO et al. Adaptive reconstruction of phased array MR imagery. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2000;43(5).

6. Feng L et al. XD-GRASP: Golden-angle radial MRI with reconstruction of extra motion-state dimensions using compressed sensing. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2016;75(2).

7. Beck A and Teboulle M. A fast iterative shrinkage-Thresholding algorithm for linear inverse problems. SIAM Journal of imaging Sciences. 2009;2(1).

8. Lee PK et al. Volumetric and multispectral DWI near metallic implants using a non-linear phase Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill diffusion preparation. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2022;87(6).

9. Uecker et al. ESPIRiT — An Eigenvalue Approach to Autocalibrating Parallel MRI: Where SENSE meets GRAPPA. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014;71(3).

Figures