1151

Data acquisition strategies to mitigate cardiac-induced noise in quantitative R2* maps of the brain1Department for Clinical Neuroscience, Laboratory for Research in Neuroimaging, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2Physics section, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland, 3Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 4Center for Biomedical Imaging (CIBM), Lausanne, Switzerland, 5Advanced Clinical Imaging Technology, Siemens Healthineers International AG, Lausanne, Switzerland, 6LTS5, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland

Synopsis

Keywords: Artifacts, Relaxometry

Cardiac pulsation enhances the noise level in MR images of the brain and reduces the sensitivity of the data in studies of brain disease. We propose two data acquisition strategies that mitigate cardiac-induced noise in quantitative brain maps of the MRI parameter R2*. The first strategy sets the number of samples at each k-space location according to the local level of cardiac-induced noise. The second strategy adjusts data acquisition in real-time to acquire the data most sensitive to cardiac-induced noise during the diastolic period of the cardiac cycle.Introduction

The transverse relaxation rate R2* correlates with e.g. iron and myelin concentration in brain tissue and enables the monitoring of microscopic disease-related changes in patients1-3. However cardiac pulsation enhances the noise level in R2* maps of the brain and reduces the sensitivity of the data to brain tissue changes4. No data acquisition strategy has been shown to mitigate cardiac-induced noise in R2* maps of the brain. Raynaud et al.5 quantified the effect of cardiac-related noise on R2* estimates and identified the affected k-space regions. From these characteristics, we propose data acquisition strategies optimized to mitigate cardiac-induced noise in R2* maps of the brain. The first mitigation strategy sets the number of samples at each k-space location according to the local level of cardiac-induced noise6. The alternative strategy synchronizes prospectively in real-time the acquisition of the most cardiac-sensitive data around the diastolic period of the cardiac cycle7-10.Methods

Multi-echo data was acquired on 5 participants using a 3T scanner (MAGNETOM Prisma, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) and a customized 3D Cartesian FLASH sequence (repetition time TR =40ms; echo times =2.34ms to 35.10ms with 2.34ms spacing). The pixel size was 2mm and 4mm along the readout and phase-encode directions. Data was acquired continuously for one hour using a sampling kernel optimized to mitigate spurious non-cardiac noise. The data were retrospectively distributed across 12 bins according to the phase of the cardiac cycle at which they were acquired, resulting in a fully sampled five-dimensional datasets (three spatial dimensions, echo time, phase of the cardiac cycle) that enabled the analysis of cardiac pulsation effects on brain R2* maps5.We conducted numerical simulations of cardiac pulsation effects in multi-echo 3D (i.e. 4D) data normally acquired to compute brain R2* maps. This data was obtained by picking data from the 5D model of cardiac-induced noise according to the k-space sampling trajectory (i.e. k-space coordinates of the data acquired consecutively in time) and a log of cardiac pulsation obtained experimentally using a pulse-oximeter. The ability of the sampling trajectories to mitigate cardiac-induced noise was assessed from the standard deviation of the R2* maps and their goodness of fit (RMSE) across repetitions with the same acquisition but different recordings of cardiac pulsation.

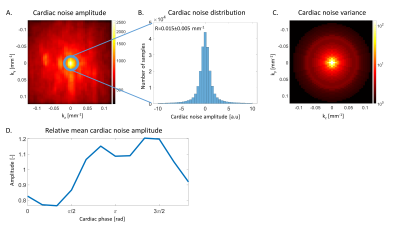

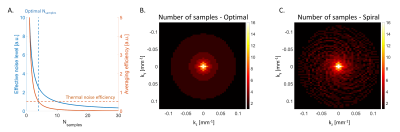

Figure 1 shows characteristics of cardiac-induced noise in k-space data. The amplitude of cardiac-induced noise is radially distributed and is highest around the origin5 (Figure 1A). Within a given radius, cardiac-induced noise follows a Gaussian distribution (Figure 1B). Figure 1C shows the variance of this distribution, estimated within all circles centred on the origin. From this result, we defined a mitigation strategy from the number of samples averaged at each k-space location (Nsamples) that produces the most efficient reduction in effective noise level. This is illustrated in figure 2A for a voxel with cardiac-induced noise variance 10 times that from thermal noise (decrease in effective noise level ~1/Nsamples). At Nsamples =4 an additional sample decreases the effective noise level by 0.5 (‘efficiency’), identical to a voxel dominated by thermal noise where only 1 sample is acquired. The most efficient number of samples in this case is therefore Nsamples =4. Figure 2B shows the distribution of the number of samples for efficient reduction in the effective noise level, which can be best reproduced with a Cartesian pseudo-spiral trajectory with 68 spiral arms with 63 multi-echoes readouts each, and a radial sampling density matched to the optimal number of samples (Figure 2C).

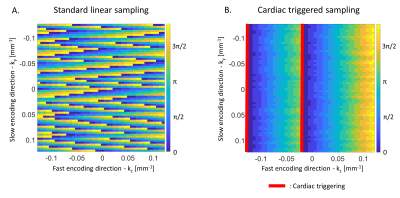

With a standard 2D linear trajectory the k-space centre, most sensitive to cardiac-induced noise, is acquired across all phases of the cardiac cycle (Figure 3A). While the cardiac phase varies smoothly along the fast encoding direction where data points are acquired consecutively every TR =40ms, abrupt changes in the cardiac phase take place along the slow encoding direction, which leads to aliasing in the reconstructed images11,12. However, cardiac-induced noise is strongest around the systolic period of the cardiac cycle ($$$\phi_c=[\pi/2,3\pi/2]$$$) and lowest around the diastolic period ($$$\phi_c=[3\pi/2,\pi/2]$$$, Figure 1D). From this, we defined a real-time mitigation strategy in which the k-space centre data is acquired during the diastole (Figure 3B), minimizing both the level of cardiac-induced noise and aliasing.

Results

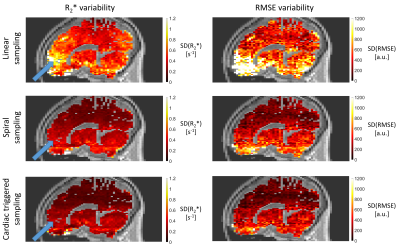

Compared to standard linear sampling, the spiral and cardiac-triggered trajectories reduce the variability of R2* by 31% and 52% and of RMSE by 30% and 50% respectively, on average over the whole brain (Figure 4). The increase in scan time for the two mitigation strategies was 72% and 29%. Both strategies lead to a strong reduction in aliasing of cardiac-induced noise from blood vessels (e.g., circle of Willis) into the brain (Figure 4, blue arrows).Discussion & conclusion

From the characteristics of cardiac-induced noise in k-space, we propose two sampling strategies to mitigate cardiac pulsation effects on brain R2* maps. The first strategy adjusts the number of samples at each k-space location to reduce the effective noise level efficiently. The alternative strategy restricts the acquisition of the sensitive k-space regions during the diastolic period of the cardiac cycle. Our results suggest that the cardiac-triggered strategy reduces cardiac-induced noise in brain R2* maps most efficiently.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Barbosa JHO, Santos AC, Tumas V, et al. Quantifying brain iron deposition in patients with Parkinson’s disease using quantitative susceptibility mapping, R2 and R2*. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015;33:559–565 doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2015.02.021.

2. Ulla M, Bonny JM, Ouchchane L, Rieu I, Claise B, Durif F. Is R2* a New MRI Biomarker for the Progression of Parkinson’s Disease? A Longitudinal Follow-Up. PLoS One 2013;8:1–8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057904.

3. Khalil M, Enzinger C, Langkammer C, et al. Quantitative assessment of brain iron by R2* relaxometry in patients with clinically isolated syndrome and relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 2009;15:1048–1054 doi: 10.1177/1352458509106609.

4. Hermes D, Wu H, Kerr AB, Wandell B. Measuring brain beats: cardiac-aligned fast fMRI signals. bioRxiv 2022:2022.02.18.480957.

5. Raynaud Q, Yerly J, Van Heeswijk RB, Lutti A. Characterization of cardiac noise in brain quantitative relaxometry MRI data. ISMRM 2022.

6. Tijssen RHN, Jenkinson M, Brooks JCW, Jezzard P, Miller KL. Optimizing RetroICor and RetroKCor corrections for multi-shot 3D FMRI acquisitions. Neuroimage 2014;84:394–405 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.062.

7. Skare S, Andersson JLR. On the effects of gating in diffusion imaging of the brain using single shot EPI. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2001;19:1125–1128 doi: 10.1016/S0730-725X(01)00415-5.

8. Nunes RG, Jezzard P, Clare S. Investigations on the efficiency of cardiac-gated methods for the acquisition of diffusion-weighted images. J. Magn. Reson. 2005;177:102–110 doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.07.005.

9. Habib J, Auer DP, Morgan PS. A quantitative analysis of the benefits of cardiac gating In practical diffusion tensor imaging of the brain. Magn. Reson. Med. 2010;63:1098–1103 doi: 10.1002/mrm.22232.

10. Bopp MHA, Yang J, Nimsky C, Carl B. The effect of pulsatile motion and cardiac-gating on reconstruction and diffusion tensor properties of the corticospinal tract. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–12 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29525-0.

11. Tijssen RHN, Okell TW, Miller KL. Real-time cardiac synchronization with fixed volume frame rate for reducing physiological instabilities in 3D FMRI. Neuroimage 2011;57:1364–1375 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.070.

12. Kristoffersen A, Goa PE. Cardiac-induced physiological noise in 3D gradient echo brain imaging: Effect of k-space sampling scheme. J. Magn. Reson. 2011;212:74–85 doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.06.012.

Figures