1148

Image-Space Self-Navigation for Respiratory Motion Compensation in 2D Axial Radial Free-Breathing MRE of the Liver1Radiological Sciences, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 2Physics and Biology in Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 3Bioengineering, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 4Gastroenterology, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 5Pediatrics, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 6Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Los Angeles, CA, United States, 7Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Austin, TX, United States, 8Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Liver

Previous work has proposed self-navigated golden-angle (GA) radial free-breathing (FB) MR elastography (MRE) of the liver. This work employed a standard DC-based motion compensation framework that proved suboptimal. Here we propose an image-space based motion-compensation framework for 2D free-breathing radial MRE. The proposed method is compared to the standard DC-based method by measuring the signal-to-noise (SNR) after self-navigated motion-compensation by each method (8 subjects). The median (interquartile range) SNR across subjects was 4.8 (3.6-5.7) and 6.8 (6.3-7.5) for the standard and proposed methods, respectively. Inclusion of image-space data may allow for more robust motion compensation for 2D radial axial acquisitions.Introduction

Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) is recognized as the most sensitive non-invasive technique for assessment of liver fibrosis.1,2 However, current clinical standard liver MRE requires breath holding,3 which is challenging for certain populations. Recent works employed a 2D golden-angle-ordered (GA) radial sampling trajectory to enable free-breathing (FB) MRE acquisition due to its motion robustness4 and capability for self-navigated motion compensation.5,6 Previous work on self-navigated radial FB-MRE relied on the repeated acquisition of the center of k-space in each radial readout (DC component).5,6,7 However, DC-based motion self-navigation is sub-optimal for 2D axial liver MRE acquisitions. FB-MRE might experience spatiotemporally varying phase/susceptibility effects and signal decay as tissue structures move in and out of the axial field-of-view (FOV) due to respiratory motion.8 This can degrade MRE magnitude/phase data fidelity, but DC-based self-navigation may not be able to resolve these effects. In this work, an image-space self-navigation framework that considers spatiotemporal variations in magnitude and phase signal is developed to facilitate more robust breathing motion compensation for 2D radial FB-MRE. The proposed self-navigation framework is compared to the DC-based self-navigation method for reconstructing 2D GA radial FB-MRE of the liver.Methods

Study PopulationIn this IRB-approved and HIPAA-compliant study, 8 consecutive subjects (4 females) aged 10-17 years with median body-mass-index (BMI) percentile (interquartile range) of 12% ([4%-30%]) were included.

MRE Acquisition

For each subject, a research application gradient-echo 2D GA radial FB-MRE4,5,6 sequence with rapid9 and fractional10 wave encoding was acquired on a 3T scanner (MAGNETOM PrismaFit, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany). Key sequence parameters included: TR: 25 ms, TE: 16.10 ms, flip angle: 12°, acquired resolution: 1.4 1.4 5mm3, 65% fractional encoding, 124 seconds/slice. The MRE wave amplitude was set to 30-70% depending on subject’s BMI. One slice per subject was included in this analysis. Each slice sequentially acquires four wave phase-offsets, with 604 radial spokes per phase-offset for acquired matrix size of 256x256 and a 1.5x oversampling factor.

Standard Self-Navigation

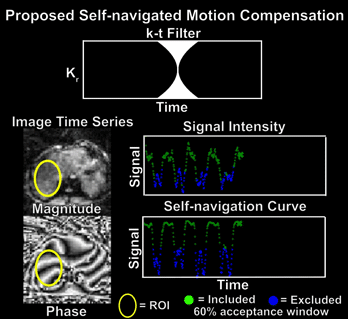

The standard self-navigation framework used the magnitude of the DC-component of the k-space signal acquired from each radial readout. Principal-component analysis (PCA) was applied to the set of DC magnitude signals from multiple coils to extract a ‘breathing curve’ (Fig. 1A-B). The most frequent ‘breathing state’ was then used as the center of the data acceptance window for motion-compensated reconstruction.

Proposed Image-Space Self-Navigation

The proposed framework treated the radial FB-MRE acquisition as a stream of time-resolved data and reconstructed dynamic images using a sliding k-t window (Fig. 1C).11 Filtered k-space data for each time-point was reconstructed with an L1-wavelet regularized conjugate gradient (CG)-SENSE algorithm using the coil-sensitivity maps estimated from all spokes.12,13 After sliding the k-t filter through every spoke, an image time-series was created (Fig. 2). A region-of-interest (ROI) at the right lobe of the liver was used to detect the highest mean signal and the corresponding time-point tmax, in the magnitude image series (Fig. 3). Then, phase-values within the same ROI were extracted at each time-point ti in the phase image series. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated between the phase values at tmax and all other ti. These correlation coefficients are used to construct a self-navigation curve for radial spoke selection (Fig. 3).

Motion Compensation and Analysis

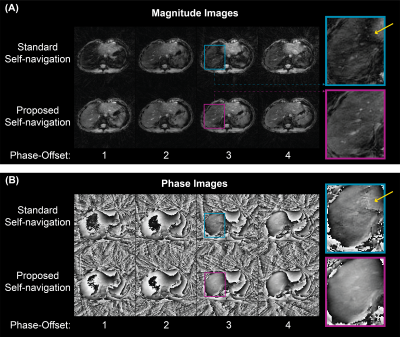

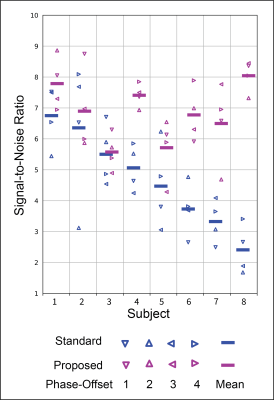

Both self-navigation algorithms were applied to every wave phase-offset with 60% acceptance window (362/604 spokes) (net under-sampling factor of 0.9). The signal-to-noise (SNR) was calculated for each phase-offset magnitude image as the mean signal in right-lobe of the liver divided by the mean signal in the background (four 25x25-pixel corners). The median and range of the SNR across subjects is reported.

Results

Examples of self-navigation image series (Fig. 3) and motion-compensated reconstruction results (Fig. 4) show that the proposed image-space method achieves higher SNR at the liver. Figure 5 displays the SNR of each magnitude image. The median (IQR) of the SNR across subjects was 4.8 (3.6-5.7) and 6.8 (6.3-7.5) using the standard and proposed self-navigation methods, respectively.Discussion

The proposed image-space self-navigation framework provides insight into the spatiotemporal variations in both magnitude and phase signals caused by breathing motion and other dynamic processes. This can be particularly useful for 2D axial acquisitions due to the limited information along the through-plane direction (superior-inferior-axis); the spatially resolved information within each 2D image provides improved characterization of motion effects. The proposed self-navigation algorithm achieved higher SNR in reconstructed images, indicating improved sensitivity to and compensation for breathing motion and associated susceptibility effects.Our study had limitations, such as a small sample size. Future work will test the algorithm in more subjects and analyze the effects on the radial FB-MRE hepatic stiffness maps. Other future work includes mapping of the self-navigation signals to physiological breathing states. Scans with a reference signal (e.g. bellows or dedicated navigator) could help accomplish this. Lastly, the self-navigation signal and final image reconstruction could be improved with more sophisticated constrained reconstruction techniques.14

Conculsion

The proposed image-space self-navigation technique can improve the spatiotemporal characterization of motion and enhance motion compensation for 2D radial free-breathing MRE of the liver.Acknowledgements

We acknowledge grant support from the National Institutes of Health (R01DK124417 and U01EB031894) and technical support from Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc. The authors thank the clinicians, study coordinators, and MRI technologists at UCLA.References

1. Xiao G, Zhu S, Xiao X, Yan L, Yang J, Wu G. Comparison of laboratory tests, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance elastography to detect fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017 Nov;66(5):1486-1501. doi: 10.1002/hep.29302. Epub 2017 Sep 26. PMID: 28586172.

2. Park CC, Nguyen P, Hernandez C, Bettencourt R, Ramirez K, Fortney L, Hooker J, Sy E, Savides MT, Alquiraish MH, Valasek MA, Rizo E, Richards L, Brenner D, Sirlin CB, Loomba R. Magnetic Resonance Elastography vs Transient Elastography in Detection of Fibrosis and Noninvasive Measurement of Steatosis in Patients With Biopsy-Proven Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2017 Feb;152(3):598-607.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.026. Epub 2016 Oct 27. PMID: 27911262; PMCID: PMC5285304.

3. Felker ER, Choi KS, Sung K, et al. Liver MR Elastography at 3 T: Agreement Across Pulse Sequences and Effect of Liver R2*on Image Quality. Am J Roentgenol 2018;211(3):588-594.

4. Kafali SG, Armstrong T, Shih SF, Kim GJ, Holtrop JL, Venick RS, Ghahremani S, Bolster BD Jr, Hillenbrand CM, Calkins KL, Wu HH. Free-breathing radial magnetic resonance elastography of the liver in children at 3 T: a pilot study. Pediatr Radiol. 2022 Jun;52(7):1314-1325. doi: 10.1007/s00247-022-05297-8. Epub 2022 Apr 2. PMID: 35366073; PMCID: PMC9192470.

5. Kafali SG, Bolster BD, Shih S-F, et al. Radial Free-Breathing Liver MR Elastography in Children using Self-Navigation and Rapid Fractional Encoding. Magnetic Resonance Elastography Workshop of International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. Berlin, Germany; 2022.

6. Kafali SG, Bolster BD, Shih S-F, et al. Self-Navigated Radial Free-Breathing Magnetic Resonance Elastography of the Liver with Rapid Motion Encoding in Children at 3T. 30th Annual Meeting of International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. London, UK; 2022.

7. Brau AC, Brittain JH. Generalized self-navigated motion detection technique: Preliminary investigation in abdominal imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2006 Feb;55(2):263-70. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20785. PMID: 16408272.

8. Zhong X, Hu HH, Armstrong T, Li X, Lee YH, Tsao TC, Nickel MD, Kannengiesser SAR, Dale BM, Deshpande V, Kiefer B, Wu HH. Free-Breathing Volumetric Liver R2* and Proton Density Fat Compensation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2021 Jan;53(1):118-129. doi: 10.1002/jmri.27205. Epub 2020 Jun 1. PMID: 32478915.

9. Chamarthi SK, Raterman B, Mazumder R, et al. Rapid acquisition technique for MR elastography of the liver. Magn Reson Imaging 2014;32(6):679-683.

10. Rump J, Klatt D, Braun J, Warmuth C, Sack I. Fractional encoding of harmonic motions in MR elastography. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2007;57(2):388-395.

11. Song HK, Dougherty L. k-space weighted image contrast (KWIC) for contrast manipulation in projection reconstruction MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2000 Dec;44(6):825-32. doi:

10.1002/1522-2594(200012)44:6<825::aid-mrm2>3.0.co;2-d. PMID: 11108618.

12. Shih S-F et al. A Beamforming-Based Coil Combination Method to Reduce Streaking Artifacts and Preserve Phase Fidelity in Radial MRI. 30th Annual Meeting of International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. London, UK; 2022.

13. Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Börnert P, Boesiger P. Advances in sensitivity encoding with arbitrary k-space trajectories. Magn Reson Med. 2001 Oct;46(4):638-51. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1241. PMID: 11590639.

14. Feng L, Axel L, Chandarana H, Block KT, Sodickson DK, Otazo R. XD-GRASP: Golden-angle radial MRI with reconstruction of extra motion-state dimensions using compressed sensing. Magn Reson Med. 2016 Feb;75(2):775-88. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25665. Epub 2015 Mar 25. PMID: 25809847; PMCID: PMC4583338.

Figures