1145

Investigating spinal cord perfusion impairment in degenerative cervical myelopathy (DCM) using Intravoxel Incoherent Motion (IVIM) MRI

Anna Lebret1, Simon Lévy2, Nikolai Pfender1, Mazda Farshad3, Virginie Callot4,5, Armin Curt1, Patrick Freund1,6, and Maryam Seif1,6

1Spinal Cord Injury Center, Balgrist University Hospital, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2MR Research Collaborations, Siemens Healthcare Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Australia, 3Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Balgrist University Hospital, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 4Aix-Marseille Univ, CNRS, CRMBM, Marseille, France, 5APHM, Hôpital Universitaire Timone, CEMEREM, Marseille, France, 6Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig, Germany

1Spinal Cord Injury Center, Balgrist University Hospital, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2MR Research Collaborations, Siemens Healthcare Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Australia, 3Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Balgrist University Hospital, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 4Aix-Marseille Univ, CNRS, CRMBM, Marseille, France, 5APHM, Hôpital Universitaire Timone, CEMEREM, Marseille, France, 6Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Spinal Cord, Neurodegeneration, Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy

Degenerative cervical myelopathy (DCM) is the most common form of non-traumatic spinal cord injury, mainly caused by chronic cervical cord compression. Impaired spinal cord perfusion is a central pathophysiological tenet in DCM patients. This study aims at investigating non-invasively DCM-induced changes of blood perfusion in the spinal cord above a cervical myelopathy using quantitative MRI techniques. Cardiac-gated intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) 3T MRI, sensitive to perfusion, was applied to the cervical cord (C1-C3) in 25 DCM patients and 27 healthy controls. DCM showed tissue-specific perfusion impairment. IVIM maps suggested remote hemodynamic deficit induced by cervical cord compression in DCM.Introduction

Cervical cord compression in DCM patients triggers a cascade of pathophysiological processes including microvascular deficits, neuroinflammation and apoptosis1–5. Impaired spinal cord perfusion plays an important role as a central pathophysiological tenet in DCM6. However, underlying mechanisms of hemodynamic changes are understudied.Therefore this study aims at using intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM), a non-invasive diffusion-based MRI method, sensitive to tissue microcirculation and perfusion7. IVIM has been previously successfully applied in different brain pathologies8–10 and other organs11–14, as well as in spinal cord at 7T15. A cardiac-gated 3T IVIM protocol was applied in the cervical cord (C1-C3) of DCM patients and healthy controls (HC) to investigate vascular impairment in the grey matter (GM) and white matter (WM) rostral to the compression site in patients.

Methods

In vivo image acquisitionClinical and MRI data were acquired in 25 DCM patients (mean age: 57.8 ± 10.2 years, 15 males, mJOA ≥14) and 27 HC (mean age: 54.3 ± 11.7 years, 11 males) on a 3T system (MAGNETOM Prisma, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with a Siemens Healthcare 64-channel head/neck RF coil. The entire protocol (38-minute nominal acquisition time) included:

- Cardiac-gated IVIM sequence: axial 2D-RF spin-echo EPI ZOOMit sequence with 0.9x0.9 mm2 in-plane resolution, 5 mm-slice thickness, 34x108 matrix size, with 14 b-values ranging from 0 to 650 s/mm2 with increment of 50 s/mm2. Twenty repetitions per b-value were acquired in three in-plane diffusion encoding directions, split into forward and reverse phase encoding acquisitions for subsequent distortion correction. FOV was centered on the C2/C3 vertebral level, covering C1-C3 levels for all subjects.

- T2*-weighted axial 3D multi-echo gradient-echo sequence, for ROI segmentation and calculation of cross-sectional areas.

- Standard axial and sagittal T2-weighted turbo spin echo sequences for lesion segmentation and cervical level localization, respectively.

As a severe compression affects the IVIM scans and subsequently biases the parameter quantification, scans were conducted above the compression level16.

Data processing and fitting

The IVIM toolbox15 was used to generate the perfusion maps. Denoising18, Gibbs artefacts removal19,20 (DIPY21), motion (sct_dmri_moco22) and distortion correction (FSL topup23) were performed. Voxel-wise fitting of the IVIM signal was based on the biexponential IVIM model7:

$$S(b)=S_0 e^{-bD} [F e^{-bD^*}+1-F]$$

where $$$F$$$ is the microvascular volume fraction, $$$D^*$$$ is the pseudo-diffusion coefficient and $$$D$$$ is the diffusion coefficient. The fit was performed using a one-step approach, with an initial estimation of $$$D$$$ using b-values ≥ 400 s/mm2 and consecutive fitting of all model parameters.

Registration to template24/atlas25 (SpinalCordToolbox version 4.322) was performed based on T2*-weighted images. Perfusion parameters $$$F$$$, $$$D^*$$$ (providing information on blood volume and blood velocity26, respectively), $$$F$$$∙$$$D^*$$$ (sensitive to blood flow26) and $$$D$$$ were extracted in subject space across C1-C3 levels, slice-by-slice, in the total spinal cord (SC), WM and GM. ROIs were eroded at the cord periphery to prevent partial volume effect.

The frequency map of the T2-hyperintensity in DCM patients with radiological myelopathy17 was calculated for presenting the frequency of lesion. Spinal cord atrophy was assessed using cross-sectional areas (CSA) derived from segmentations of the T2*-weighted MRI. Two-sample t-tests were conducted in R (version 4.1.2) to compare IVIM-derived perfusion parameters and CSA between HC and DCM. Relationships between perfusion parameters and CSA were explored using linear regression and Pearson's correlation coefficient.

Results & Discussion

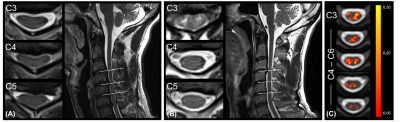

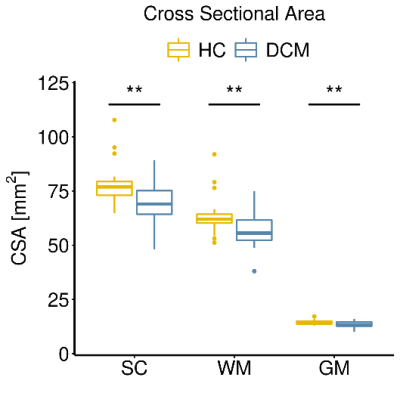

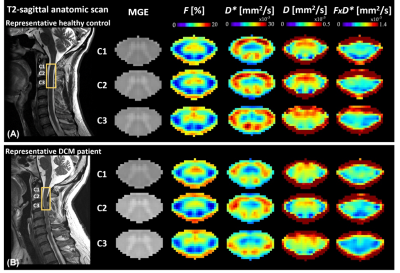

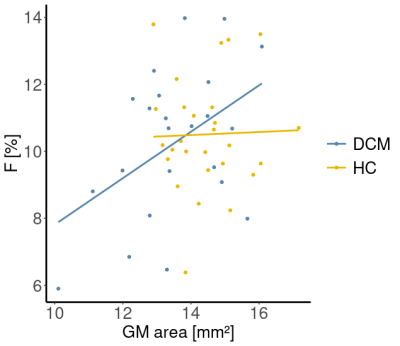

Eight DCM patients showed radiological evidence of cervical myelopathy (n=2 at C3/C4, n=2 at C4/C5, and n=4 at C5/C6) (Figure 1B). The lesion frequency maps indicated higher frequency of myelopathy in GM at C3-C5 levels in the DCM group (Figure 1C). Atrophy was observed in WM (Δ = -9.7%; p = 0.006) and GM (Δ = -6.8%; p = 0.005) of DCM patients (Figure 2), which is in agreement with previous findings27. Perfusion maps, averaged across subjects, depicted the distribution of the IVIM parameters in different ROIs (Figure 3). $$$F$$$ was greater in GM compared to WM in both cohorts, in alignment with previous studies15,28,29. The maps visually suggested a gradient of $$$F$$$ in GM in DCM, decreasing from C1 to C3 (Figure 3B). While $$$D^*$$$ and blood flow ($$$F$$$∙$$$D^*$$$) were reduced in GM, cord region mainly affected by DCM1, only $$$D^*$$$ decreased in WM of DCM (Figure 4B-C). Of note, a positive correlation was found between $$$F$$$ and GM area (Figure 5). Although group interaction (HC ~ DCM) was not significant, post-hoc analysis indicated that the correlation was mainly driven by DCM (R = 0.69, p = 0.02), while no correlation was observed in HC (R = 0.04, p = 0.90). This suggests a possible alteration in microvasculature volume in GM related to the atrophy observed in DCM patients.Conclusion

Perfusion maps provide novel insights into tissue-specific changes in DCM, with regard to blood flow and velocity, indicating perfusion deficit in the rostral atrophied cervical cord. Current findings suggest that IVIM is sensitive to the hemodynamic impairment in the cervical cord of DCM. In the next steps, we will explore different optimization approaches (e.g. Bayesian methods30) for the IVIM fit and track perfusion deficit longitudinally following traumatic injury.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants for their time. This work is based on experiments performed at the Swiss Center for Musculoskeletal Imaging, SCMI, Balgrist Campus AG, Zurich. This project has received funding from the Wings for Life charity (No WFL-CH-19/20) and Balgrist Stiftung 2021.References

1. Fehlings MG, Skaf G. A Review of the Pathophysiology of Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy With Insights for Potential Novel Mechanisms Drawn From Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: Spine. 1998;23(24):2730-2736. doi:10.1097/00007632-199812150-000122. Schubert M. Natural Course of Disease of Spinal Cord Injury. In: Weidner N, Rupp R, Tansey KE, eds. Neurological Aspects of Spinal Cord Injury. Springer International Publishing; 2017:77-105. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46293-6_4

3. Seif M, David G, Huber E, Vallotton K, Curt A, Freund P. Cervical Cord Neurodegeneration in Traumatic and Non-Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37(6):860-867. doi:10.1089/neu.2019.6694

4. David G, Vallotton K, Hupp M, Curt A, Freund P, Seif M. Extent of Cord Pathology in the Lumbosacral Enlargement in Non-Traumatic versus Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2022;39(9-10):639-650. doi:10.1089/neu.2021.0389

5. Vallotton K, David G, Hupp M, et al. Tracking White and Gray Matter Degeneration along the Spinal Cord Axis in Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38(21):2978-2987. doi:10.1089/neu.2021.0148

6. Badhiwala JH, Ahuja CS, Akbar MA, et al. Degenerative cervical myelopathy — update and future directions. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(2):108-124. doi:10.1038/s41582-019-0303-0

7. Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, Aubin ML, Vignaud J, Laval-Jeantet M. Separation of diffusion and perfusion in intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;168(2):497-505. doi:10.1148/radiology.168.2.3393671

8. Spinner GR, Federau C, Kozerke S. Bayesian inference using hierarchical and spatial priors for intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging in the brain: Analysis of cancer and acute stroke. Med Image Anal. 2021;73:102144. doi:10.1016/j.media.2021.102144

9. Bisdas S, Klose U. IVIM analysis of brain tumors: an investigation of the relaxation effects of CSF, blood, and tumor tissue on the estimated perfusion fraction. Magn Reson Mater Phys Biol Med. 2015;28(4):377-383. doi:10.1007/s10334-014-0474-z

10. Bertleff M, Domsch S, Weingärtner S, et al. Diffusion parameter mapping with the combined intravoxel incoherent motion and kurtosis model using artificial neural networks at 3 T. NMR Biomed. 2017;30(12):e3833. doi:10.1002/nbm.3833

11. Spinner GR, von Deuster C, Tezcan KC, Stoeck CT, Kozerke S. Bayesian intravoxel incoherent motion parameter mapping in the human heart. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2017;19(1):85. doi:10.1186/s12968-017-0391-1

12. Lemke A, Laun FB, Klau M, et al. Differentiation of Pancreas Carcinoma From Healthy Pancreatic Tissue Using Multiple b-Values: Comparison of Apparent Diffusion Coefficient and Intravoxel Incoherent Motion Derived Parameters. Invest Radiol. 2009;44(12):769-775. doi:10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181b62271

13. Notohamiprodjo M, Chandarana H, Mikheev A, et al. Combined intravoxel incoherent motion and diffusion tensor imaging of renal diffusion and flow anisotropy: IVIM-DTI of the Kidney. Magn Reson Med. 2015;73(4):1526-1532. doi:10.1002/mrm.25245

14. Seif M, Mani LY, Lu H, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of the human kidney: Does image registration permit scanning without respiratory triggering?: Registration for DTI of Kidneys. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;44(2):327-334. doi:10.1002/jmri.25176

15. Lévy S, Rapacchi S, Massire A, et al. Intravoxel Incoherent Motion at 7 Tesla to quantify human spinal cord perfusion: limitations and promises. Magn Reson Med. 2020;84(3):1198-1217. doi:10.1002/mrm.28195

16. Cohen-Adad J. Microstructural imaging in the spinal cord and validation strategies. NeuroImage. 2018;182:169-183. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.04.009

17. Scheuren PS, David G, Kramer JLK, et al. Combined Neurophysiologic and Neuroimaging Approach to Reveal the Structure-Function Paradox in Cervical Myelopathy. Neurology. 2021;97(15):e1512-e1522. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000012643

18. Manjón JV, Coupé P, Concha L, Buades A, Collins DL, Robles M. Diffusion Weighted Image Denoising Using Overcomplete Local PCA. Gong G, ed. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e73021. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073021

19. Kellner E, Dhital B, Kiselev VG, Reisert M. Gibbs-ringing artifact removal based on local subvoxel-shifts: Gibbs-Ringing Artifact Removal. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76(5):1574-1581. doi:10.1002/mrm.26054

20. Perrone D, Aelterman J, Pižurica A, Jeurissen B, Philips W, Leemans A. The effect of Gibbs ringing artifacts on measures derived from diffusion MRI. NeuroImage. 2015;120:441-455. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.06.068

21. Garyfallidis E, Brett M, Amirbekian B, et al. Dipy, a library for the analysis of diffusion MRI data. Front Neuroinformatics. 2014;8. doi:10.3389/fninf.2014.00008

22. De Leener B, Lévy S, Dupont SM, et al. SCT: Spinal Cord Toolbox, an open-source software for processing spinal cord MRI data. NeuroImage. 2017;145:24-43. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.10.009

23. Andersson JLR, Skare S, Ashburner J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. NeuroImage. 2003;20(2):870-888. doi:10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00336-7

24. De Leener B, Fonov VS, Collins DL, Callot V, Stikov N, Cohen-Adad J. PAM50: Unbiased multimodal template of the brainstem and spinal cord aligned with the ICBM152 space. NeuroImage. 2018;165:170-179. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.10.041

25. Lévy S, Benhamou M, Naaman C, Rainville P, Callot V, Cohen-Adad J. White matter atlas of the human spinal cord with estimation of partial volume effect. NeuroImage. 2015;119:262-271. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.06.040

26. Bihan DL, Turner R. The capillary network: a link between ivim and classical perfusion. Magn Reson Med. 1992;27(1):171-178. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910270116

27. Grabher P, Mohammadi S, Trachsler A, et al. Voxel-based analysis of grey and white matter degeneration in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):24636. doi:10.1038/srep24636

28. Hassler O. Blood Supply to Human Spinal Cord: A Microangiographic Study. Arch Neurol. 1966;15(3):302. doi:10.1001/archneur.1966.00470150080013

29. Lévy S, Roche P, Guye M, Callot V. Feasibility of human spinal cord perfusion mapping using dynamic susceptibility contrast imaging at 7T: Preliminary results and identified guidelines. Magn Reson Med. 2021;85(3):1183-1194. doi:10.1002/mrm.28559

30. Orton MR, Collins DJ, Koh DM, Leach MO. Improved intravoxel incoherent motion analysis of diffusion weighted imaging by data driven Bayesian modeling: Improved IVIM Analysis with Bayesian Modelling. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(1):411-420. doi:10.1002/mrm.24649

Figures

Figure 1: Overview of the site of compression in DCM

patients (A) without and (B) with radiological hyperintensity myelopathy. (C)

Frequency map of radiological hyperintense signal along the cord of DCM

patients with cervical myelopathy (n = 8) overlaid on the PAM50 template.

Figure 2: Cervical cord atrophy in DCM patients. Box and

whisker plots of cross-sectional areas (CSA) of total spinal cord (SC), white

matter (WM) and grey matter (GM) in the cervical cord averaged across C1-C3

levels of healthy controls (HC) and DCM patients. **p < 0.01.

Figure 3: Sagittal T2-weighted and axial T2*-weighted images of the cervical cord, as well as IVIM mean maps including microvascular volume fraction $$$F$$$ [%], pseudo-diffusion coefficient $$$D^*$$$ [mm2/s], diffusion coefficient $$$D$$$ [mm2/s], and blood flow-related coefficient $$$F$$$∙$$$D^*$$$ [mm2/s] at C1-C3 levels. Maps were averaged across diffusion-encoding directions and subjects in (A) healthy controls and (B) DCM patients. A representative subject of each cohort is shown on the left.

Figure 4: IVIM parameters comparison between DCM and

healthy controls (HC). Box and whisker plots of IVIM parameters: (A)

microvascular volume fraction $$$F$$$ [%], (B) pseudo-diffusion coefficient $$$D^*$$$ [mm2/s] and (C) blood flow-related

coefficient $$$F$$$∙$$$D^*$$$ [mm2/s] averaged across slices over

C1-C3 levels in HC and DCM groups in the total spinal cord (SC), white matter (WM) and grey matter (GM). *p < 0.05.

Figure 5: Correlation between perfusion fraction and

atrophy. Linear regression models of the perfusion fraction $$$F$$$ [%] and grey matter (GM) area [mm2]

averaged across C1-C3 levels in healthy controls (HC) and DCM patients. HC: R =

0.045, p = 0.90. DCM: R = 0.69, p = 0.02.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1145