1138

Assessing microstructural and microvascular abnormalities in hospitalized COVID-19 patients using intravoxel incoherent motion imaging1School for Mental Health & Neuroscience, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands, 2Department of Intensive Care, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, Netherlands, 3Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, Netherlands, 4Limburg Brain Injury Center, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands, 5Department of Intensive Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands, 6UMC Utrecht Brain Center, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands, 7Department of Intensive Care, University Medical Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 8Amsterdam Neuroscience, University Medical Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 9Department of Neuropsychology and Psychopharmacology, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands, 10Department of Electrical Engineering, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Infectious disease, COVID-19

Cerebral abnormalities are common in (severely affected) COVID-19 patients, although most reports only cover macrostructural abnormalities. Zooming in on microstructural abnormalities may better explain persisting COVID-19-related symptoms in COVID-19 survivors. Using intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) imaging, this study explored potential differences in microstructural and microvascular diffusivity between COVID-19 patients. No differences were found between patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) (n=40) and general ward (n=38). However, increased disease severity in COVID-19 ICU patients was found to be associated with increased interstitial fluid content in the normal appearing white matter.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) primarily leads to pneumonia in severely affected patients – resulting in severe inflammation and hypoxemia – but also affects other organs, including the brain. An increasing number of studies are bringing a wide spectrum of cerebral abnormalities to light, including parenchymal and cerebrovascular abnormalities, e.g. abnormal cerebral diffusivity (1), abnormal perfusion (2,3) and microbleeds (4).Most of these complications are characterized on a macroscale level using clinical MRI sequences. More subtle changes may therefore go unnoticed, whereas these can contribute considerably to our understanding of persisting COVID-19-related symptoms. Intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) imaging is a diffusion-weighted imaging technique that allows estimation of diffusivity on a microscale, in both the parenchyma and microvasculature (5). An additional contribution of interstitial fluid (ISF) to the diffusion-weighted signal can be distinguished using spectral analysis (6), which was previously shown to relate to cognitive impairment and white matter injury (6,7).

This study aims to explore the effect of COVID-19 severity on microstructural and microvascular diffusivity using IVIM by 1) comparing COVID-19 hospitalization (i.e., admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) versus admission to the general ward (non-ICU)), and 2) relating an ICU disease severity score to the IVIM measures.

Methods

Subjects and clinical data: Seventy-eight COVID-19 patients (40 ICU and 38 non-ICU) from the NeNeSCo cohort were included in this study (8). All patients were hospitalized during the first COVID-19 wave and scanned approximately 8-10 months after hospitalization. The highest recorded Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score over the course of ICU stay was used as an additional measure for disease severity (9). The SOFA score is useful in predicting clinical outcomes of critically ill patients, ranging from 0 (best) to 24 (worst).MRI acquisition: Brain imaging for all patients was performed on a 3.0 Tesla MR system (Philips, Ingenia CX, Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) at two sites using a 32-channel head coil. Multi-b-value diffusion-weighted MR images and anatomical T1-weighted and T2-weighted FLAIR images were acquired (Table 2).

Image processing: Regions of interest (ROIs) included normal appearing white matter (NAWM), cortical grey matter (cGM), and white matter hyperintensities (WMH). NAWM and cGM were automatically segmented from T1-weighted images using FreeSurfer (version 7.1.0), and WMHs were automatically segmented from FLAIR images using FreeSurfer SAMSEG (10). All ROIs were coregistered to native IVIM space (FLIRT, FSL version 6.0.4) (11). Diffusion MR images were corrected for head displacements, geometric susceptibility distortions, and eddy currents (ExploreDTI version 4.8.6)(12).

IVIM analysis: Trace images were calculated by averaging the three acquired diffusion sensitized directions. IVIM data was analyzed in a voxelwise manner with spectral analysis using regularized non-negative least squares (rNNLS), with 200 basis functions (6,13). The spectrum was divided into three ranges: parenchymal diffusion (Dpar) 0.1<D<1.5*10-3 mm2/s, intermediate diffusion component (Dint) 1.5<D<4.0*10-3 mm2/s, and microvascular perfusion (Dmv) 4.0<D<200*10-3 mm2/s (6). The contribution of the diffusion components to the signal was determined by quantifying the volume fraction of parenchymal (fpar), intermediate (fint), and microvascular (fmv) diffusion components, while correcting for T1- and T2-relaxation effects (6). Median values of IVIM measures were extracted for each ROI.

Statistical analysis: IVIM measures were compared between ICU and non-ICU patients using multivariable linear regression, correcting for age, sex, and inclusion site (Matlab 2020a, MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts). To further examine the relation between disease severity and IVIM measures, SOFA scores were added to a linear model with only ICU patients, together with age, sex, and inclusion site.

Results

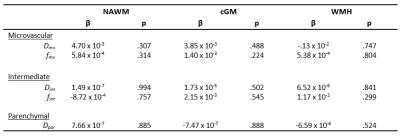

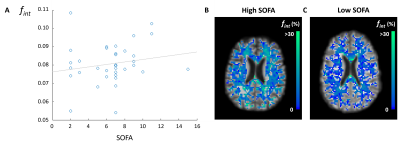

Patient characteristics are described in Table 1. Group means of the IVIM measures for each ROI are reported in Table 3. No significant differences were found for spectral IVIM parameters between the ICU and non-ICU COVID-19 patients (Table 4). Taking a disease severity score into account, a higher SOFA score was significantly associated with higher fint in the NAWM of ICU patients (Figure 1). No other significant associations were found.Discussion

This study assessed the effect of COVID-19 severity on microstructural and microvascular diffusivity using IVIM. Obtained values for IVIM measures were of similar order as previously reported (7), highlighting the validity of current values. No significant differences were observed between ICU and non-ICU COVID-19 patients for any IVIM measure in any ROI. However, in ICU patients, a higher SOFA score – indicating increased disease severity – was associated with a higher fint in the NAWM.The absence of significant differences between ICU and non-ICU COVID-19 patients suggests similar levels of long-term cerebral damage as assessed by IVIM. This is in agreement with previous work reporting long-term COVID-19 symptoms being related to the severity of the infection, regardless of hospitalization status (14).

In more severely affected COVID-19 ICU patients, higher fint was found in the NAWM. Higher fint is likely related to more ISF in the tissue and reflects breakdown of WM tissue. No such relations were observed in the WMH, suggesting that disease severity is not related to the extent of damage within WMH.

Conclusion

Our results suggest IVIM can pick up on abnormalities beyond WMH in the (normal appearing) WM, which are possibly related to early stages of tissue damage processes. Such subtle abnormalities may pave the way to understand long-term cerebral abnormalities of COVID-19.Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by The Brain Foundation Netherlands, grant number DR-2020-00377.

References

1. Douaud G, Lee S, Alfaro-Almagro F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature 2022;604(7907):697-707.

2. Chougar L, Shor N, Weiss N, et al. Retrospective Observational Study of Brain MRI Findings in Patients with Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Neurologic Manifestations. Radiology 2020;297(3):E313-e323.

3. Lersy F, Bund C, Anheim M, et al. Evolution of Neuroimaging Findings in Severe COVID-19 Patients with Initial Neurological Impairment: An Observational Study. Viruses 2022;14(5).

4. Hernández-Fernández F, Sandoval Valencia H, Barbella-Aponte RA, et al. Cerebrovascular disease in patients with COVID-19: neuroimaging, histological and clinical description. Brain 2020;143(10):3089-3103.

5. Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, Aubin ML, Vignaud J, Laval-Jeantet M. Separation of diffusion and perfusion in intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging. Radiology 1988;168(2):497-505.

6. Wong SM, Backes WH, Drenthen GS, et al. Spectral Diffusion Analysis of Intravoxel Incoherent Motion MRI in Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 2020;51(4):1170-1180.

7. van der Thiel MM, Freeze WM, Verheggen ICM, et al. Associations of increased interstitial fluid with vascular and neurodegenerative abnormalities in a memory clinic sample. Neurobiol Aging 2021;106:257-267.

8. Klinkhammer S, Horn J, Visser-Meilij JMA, et al. Dutch multicentre, prospective follow-up, cohort study comparing the neurological and neuropsychological sequelae of hospitalised non-ICU- and ICU-treated COVID-19 survivors: a study protocol. BMJ Open 2021;11(10):e054901.

9. Lambden S, Laterre PF, Levy MM, Francois B. The SOFA score-development, utility and challenges of accurate assessment in clinical trials. Crit Care 2019;23(1):374.

10. Puonti O, Iglesias JE, Van Leemput K. Fast and sequence-adaptive whole-brain segmentation using parametric Bayesian modeling. Neuroimage 2016;143:235-249.

11. Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage 2002;17(2):825-841.

12. Leemans A, Jeurissen B, Sijbers J, Jones DK. ExploreDTI: a graphical toolbox for processing, analyzing, and visualizing diffusion MR data. 2009.

13. Drenthen GS, Backes WH, Aldenkamp AP, Jansen JFA. Applicability and reproducibility of 2D multi-slice GRASE myelin water fraction with varying acquisition acceleration. Neuroimage 2019;195:333-339.

14. Sivan M, Parkin A, Makower S, Greenwood DC. Post-COVID syndrome symptoms, functional disability, and clinical severity phenotypes in hospitalized and nonhospitalized individuals: A cross-sectional evaluation from a community COVID rehabilitation service. J Med Virol 2022;94(4):1419-1427.

Figures

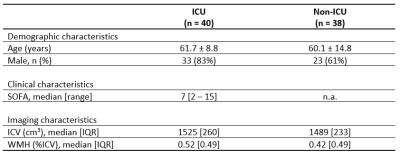

Table 1. Patient characteristics. Mean (standard deviation) are reported unless stated otherwise.

Abbreviations: ICU = intensive care unit, SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, ICV = intracranial volume, WMH = white matter hyperintensities.

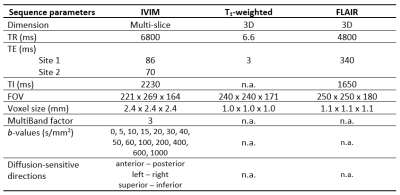

Table 2. Summarized sequence parameters.

Abbreviations: IVIM = intravoxel incoherent motion, FLAIR = fluid-attenuation inversion recovery, TR = repetition time, TE = echo time, TI = inversion time, FOV = field of view.

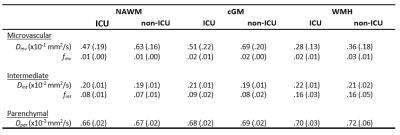

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of IVIM measures. Mean (standard deviation) are reported.

Abbreviations: IVIM = intravoxel incoherent motion, ICU = intensive care unit, NAWM = normal appearing white matter, cGM = cortical grey matter, WMH = white matter hyperintensities, Dpar = parenchymal diffusivity, Dint = interstitial fluid diffusivity, fint = interstitial fluid diffusion volume fraction, Dmv = microvascular diffusivity, fmv = microvascular diffusion volume fraction.

Table 4. Multivariable linear regression results. Unstandardized beta coefficients and p-values are reported.

Abbreviations: IVIM = intravoxel incoherent motion, ICU = intensive care unit, NAWM = normal appearing white matter, cGM = cortical grey matter, WMH = white matter hyperintensities, Dpar = parenchymal diffusivity, Dint = interstitial fluid diffusivity, fint = interstitial fluid diffusion volume fraction, Dmv = microvascular diffusivity, fmv = microvascular diffusion volume fraction.

Figure 1. Relation of disease severity and fint in NAWM. Higher fint values in NAWM were observed in COVID-19 ICU patients with a higher SOFA score (p = .017) (A). For illustrative purposes, a reference line was added. The fint map in NAWM of a COVID-19 ICU patient with a high (B) and low SOFA score (C) are shown.

Abbreviations: NAWM = normal appearing white matter, SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, ICU = intensive care unit, fint = interstitial fluid diffusion volume fraction.