1122

Knee Bone and Cartilage Segmentation using Deep Learning Model Trained with Heterogeneous Data: Preliminary Results1Grossman School of Medicine, New York University, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Cartilage, Joints

In this study, we pre-trained a deep learning model for knee bone and cartilage segmentation with open dataset (MICCAI grand challenge "K2S 2022"), and then fine-tuned it with a small size of locally acquired data for customized task, in which we explored different contrasts as well. We can benefit from the large dataset size to increase the segmentation accuracy and generalization capabilities while reducing the labor and time of manual segmentation for training data. The preliminary results of a small dataset with 10 subjects using a simple 2D U-net are promising for single contrast and multi contrast images.Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a chronic and the most pervasive knee joint disorder occurring in a large population [10,5]. Biomarkers derived from knee bone and cartilage segmentation show clinical potentials in diagnosis and treatment planning of OA [4]. MRI is extensively used for knee segmentation for its multi-planar capability and excellent soft-tissue contrast [12,7,3]. Although being a golden standard, the manual segmentation is tedious and labor-intensive with subjective bias. In recent years, automatic deep learning-based (DL-based) methods of knee segmentation from MRI images had a significant improvement [2,1,8]. Large-size data is required to learn anatomy and prevent overfittings. The data is generally homogeneous and acquired with the same sequence from one site. However, it is not always practical to acquire large amounts of data and to conduct manual segmentation. It is time-consuming and labor-intensive. One effective alternative is to start the network training with pre-trained models. Also, the use of heterogeneous data will increase the segmentation accuracy and the network’s generalization capabilities [9, 11]. Therefore, using the open dataset can enlarge the training data size, which will reduce the burden of acquiring data while preserving high segmentation performance. Here, we propose to initially pre-train the segmentation DL model with an open knee dataset and fine-tune it with the local data acquired with a specific sequence for customized purposes. In addition to that, we explored the segmentation performance for multi contrast images in the fine-tuning step.Methods

Data acquisition and pre-processing: The open dataset used was downloaded through the K2S challenge of MICCAI 2022 (https://k2s.grand-challenge.org/Home/). It contains 300 subjects and was acquired from 3T GE MRI scanner using 3D CUBE sequences. The local dataset was acquired on a 3T Siemens MRI scanner after getting informed consent for 10 healthy subjects. A Turbo FLASH sequence was used with a 15-channel knee coil with parameters such as: TR = 1500ms, TE = 3.67ms, 2 mm slice thickness. 5 TSLs (0.5ms, 4.3ms, 9ms, 33ms, and 55ms) were set for different contrasts. More details about the acquisition can be found in [5]. Both datasets were reconstructed using ESPIRiT [12 ] and normalized to [0,1]. We reduced the size of the open dataset images from 512×512 to 256×256, to aleviate the computational burden for reconstruction and model training. The knee images were segmented into background, femoral cartilage, tibial cartilage, patellar cartilage, femur, tibia and patella. The open dataset contains segmentation. For the local dataset, manual segmentation was conducted by an experienced researcher.Image segmentation: We used a 2D U-net [9] model for the segmentation. The magnitude of the coil-combined images of the sagittal view were passed through the network. In the pre-training, the model was initialized randomly and the SGD optimizer was used with a batch size of 12. A scheduler was set with learning rate starts at 0.1 and decay by half every 30 epochs. We trained it with Cross-Entropy and then switched over to Focal loss after convergence. The 300 subjects were randomly split into 240, 30 and 30 for training, validation and testing, respectively. Then, the pre-trained network was fine-tuned by the local data of 10 subjects, randomly splitting into 7, 1 and 2 for training, validation and testing, respectively. The learning rate was set to 0.001 with the same settings as the pre-trained model for the remaining parameters. To investigate the capability of the network for multi-contrast images, we trained two different networks in the fine-tuning step. One network was fine-tuned with only 1 contrast images of TSL=0.5ms, while the other one was trained with all images of 5 different TSLs.Evaluation metric: The performance is evaluated with the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) and the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) between the predicted and manual segmentations.Results

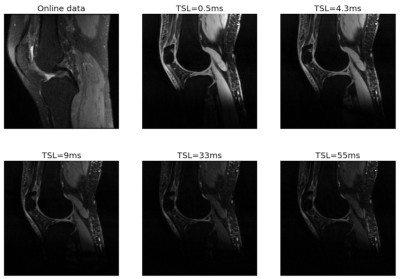

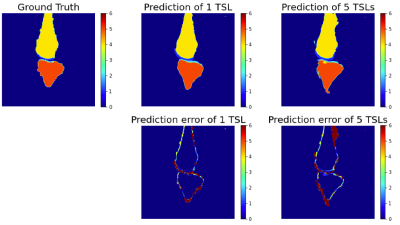

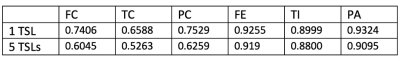

Fig. 1 compares the images of one local subject acquired with 5 TSLs and one similar image from the open dataset. All images show some difference in contrast but similar anatomy.Figure 2 depicts the segmentation for the 1-TSL image and 5-TSL image of a subject. Overall, the performance of both bone and cartilage is good while the 1 TSL has high performance than 5-TSL, and we observed this for most images in the test data. We noticed the network over-estimated the structures at edges.Table 1 shows the DSC of each region of the segmentation. The performance of the network reaches a high value in bones but less accurate for the cartilage due to the thin and small anatomy of the structures. For the SSIM, our approach reaches 0.992 and 0.987 for the 1-TSL network and 5-TSL network, respectively.Discussion and Conclusion

We demonstrated that, when pre-trained with a large open dataset followed by refinement with a small local dataset, a simple 2D U-net is capable of predicting the knee structures with a relatively good performance (mean DSC=0.8184) even though the datasets are heterogeneous. The network works for multi-contrast images, with promising performance (mean DSC = 0.7440). This preliminary result with only 10 subjects has potential to improve when increasing the size of the fine-tuning dataset. Future work will include the acquisition of more local data and explore more advanced loss functions focusing on the cartilages since it’s more challenging with small anatomy.Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH grants, R21-AR075259-01A1, R01-AR068966, R01-AR076328-01A1, R01-AR076985-01A1, and R01-AR078308-01A1 and was performed under the rubric of the Center of Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research (CAI2R), an NIBIB Biomedical Technology Resource Center (NIH P41-EB017183).References

[1] R. Almajalid, M. Zhang, and J. Shan. Fully automatic knee bone detection and segmentationon three-dimensional mri. Diagnostics, 12(1):123, 2022.

[2] F. Ambellan, A. Tack, M. Ehlke, and S. Zachow. Automated segmentation of knee bone andcartilage combining statistical shape knowledge and convolutional neural networks: Data fromthe osteoarthritis initiative. Medical image analysis, 52:109–118, 2019.

[3] A. S. Chaudhari, F. Kogan, V. Pedoia, S. Majumdar, G. E. Gold, and B. A. Hargreaves.Rapid knee mri acquisition and analysis techniques for imaging osteoarthritis. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 52(5):1321–1339, 2020.

[4] P. Conaghan, D. Hunter, J.-F. Maillefert, W. Reichmann, and E. Losina. Summary andrecommendations of the oarsi fda osteoarthritis assessment of structural change working group.Osteoarthritis and cartilage, 19(5):606–610, 2011.

[5] H. L. de Moura, M. V. W. Zibetti, and R. Regatte. Spin-lock times selection for optimizedt1ρ-mapping of knee cartilage on bi-exponential and stretched-exponential models.

[6] H. S. Fahmy, N. H. Khater, N. M. Nasef, and N. M. Nasef. Role of mri in assessment ofpatello-femoral derangement in patients with anterior knee pain. The Egyptian Journal ofRadiology and Nuclear Medicine, 47(4):1485–1492, 2016.

[7] A. A. Gatti and M. R. Maly. Automatic knee cartilage and bone segmentation using multi-stage convolutional neural networks: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Magnetic ResonanceMaterials in Physics, Biology and Medicine, 34(6):859–875, 2021.

[8] D. A. Kessler, J. W. MacKay, V. A. Crowe, F. M. Henson, M. J. Graves, F. J. Gilbert, and J. D. Kaggie. The optimisation of deep neural networks for segmenting multiple knee joint tissuesfrom mris. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics, 86:101793, 2020.

[9] O. Ronneberger, P. Fischer, and T. Brox. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention, pages 234–241. Springer, 2015.

[10] C.-K. Shie, C.-H. Chuang, C.-N. Chou, M.-H. Wu, and E. Y. Chang. Transfer representationlearning for medical image analysis. In 2015 37th annual international conference of the IEEEEngineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), pages 711–714. IEEE, 2015.

[11] S. Thomas, D. Rupiper, and G. S. Stacy. Imaging of the patellofemoral joint. Clinics in Sports medicine, 33(3):413–436, 2014.

[12] M. Uecker, P. Lai, M. J. Murphy, P. Virtue, M. Elad, J. M. Pauly, S. S. Vasanawala, andM. Lustig. Espirit—an eigenvalue approach to autocalibrating parallel mri: where sense meetsgrappa. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 71(3):990–1001, 2014.

Figures