1080

Acute Effects of Electronic and Tobacco Cigarette Aerosol Inhalation on Vascular Function Detected at Quantitative MRI1Department of Radiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States, 2Department of Neurosciences, Imaging and Clinical Sciences, G. d’Annunzio University’ of Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy, 3Institute for Advanced Biomedical Technologies (ITAB), G. d’Annunzio University’ of Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy, 4Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Vessels, Blood vessels, Vascular Reactivity, Oxygenation, Blood Velocity

To assess the acute effects of tobacco and electronic cigarette inhalation on vascular function, multiple MRI markers were analyzed in a study targeting peripheral, central and neurovascular beds of healthy young subjects. Smokers and vapers (9 subjects for a total N=15 study visits), ages 22 to 45 years, underwent two MRI scans, with a smoking or vaping challenge in between. Data from smoking/vaping challenges were combined to assess for their pooled effect. Smoking/vaping had significant acute effects on peripheral reactivity, notably on the superficial femoral artery flow-mediated dilation, baseline velocity and superficial femoral vein baseline oxygen saturation, among others.Introduction

The prevalent electronic cigarette use is encouraged by its misleading marketing as a safer alternative to tobacco cigarette (t-cig) smoking and as an adjuvant in helping quit smoking1,2. In light of the controversial data about the electronic, notably non-nicotinized, cigarettes’ safety profile, this study aims to assess the acute effects of tobacco, nicotinized and non-nicotinized electronic cigarette (e-cig) use on vascular function in smokers and vapers. In this study, an array of previously validated MRI biomarkers3, expanded to include assessment of cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) and neurovascular compliance (NVC), was applied to evaluate the acute effects of smoking and vaping challenges on the vascular system.Methods

In this ongoing, double-blinded study, nine smokers (t-cig users), vapers (e-cig users) and dual users, who have been smoking and/or vaping for at least six months, and ten non-smokers have been studied so far. The smokers/vapers, ages 22 to 45 years, consisted of three females and six males. The non-smokers, ages 21 to 33 years, consisted of eight females and two males. Participants were asked to fast, refrain from taking vasoactive medications, doing excessive exercise and smoking/vaping (if smokers/vapers) for eight hours prior to the visit. They were normotensive during the visits. The study, performed on a 3 Tesla system (Siemens Prisma, headquarter in Erlangen, Germany), involved a cross-over design where each smoker/vaper underwent an MRI examination before and after a smoking or vaping challenge separated in time by at least three days. Interventions consisted of t-cig smoking, nicotinized- and non-nicotinized e-cig vaping challenges. Investigators were blinded to the type of aerosol inhaled. Three of the smokers/vapers underwent the protocol three times for a total N=15 scan sessions. The non-smokers underwent one MRI examination (no smoking/vaping challenge). Most of the elements of the MRI protocol have been described previously by some of the investigators3. In brief, an 8-channel knee coil, 18-channel body as well as spine coils and a 20-channel head/neck coil were used to evaluate superficial femoral artery and vein, aortic arch, superior sagittal sinus (SSS) and common carotid arteries (CCA). A 5-minute Hokanson cuff occlusion was applied at the proximal thigh at a pressure of 215 mmHg. High-resolution cross-sectional images of the femoral artery were acquired in the thigh distal to the cuff, at baseline and during hyperemia, to detect luminal flow-mediated dilation (FMD). During hyperemia, femoral arterial flow velocity and venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) were quantified (Figure 1). Aortic stiffness was assessed by quantifying aortic arch pulse wave velocity through complex difference projections. Velocity-encoded projections were obtained without gating4 (Figure 2). Phase-contrast imaging the SSS yielded cerebrovascular reactivity via breath-hold-index as the slope of the velocity-time curve during a 30-second breath-hold challenge repeated three times (Figure 2). The SSS flow velocity and SvO2 allowed a derivation of the CMRO2 based on Fick’s principle. Lastly, we quantified a surrogate measure of the NVC computed at the CCA. The blood flow was time resolved with 1D-MR velocimetry5. NVC was computed by quantifying the excess blood volume in the arterial tree in the brain during systole relative to the average flow rate (Figure 2). Paired t-tests were performed to assess for differences between pre- and post-challenge biomarkers in smokers/vapers. The data from all smoking and vaping challenges were combined to determine their collective effect because the study is ongoing and the type of challenge undergone by each subject was not unblinded to the investigators. Subsequently, ANOVA single factor was done to evaluate for differences between pre- and post-challenge biomarkers between the three different types of challenges (tobacco smoking, vaping of nicotinized and non-nicotinized aerosol). Lastly, unpaired t-tests were performed to assess for differences between the biomarkers in non-smokers and the baseline biomarkers in smokers/vapers (pre-challenge).Results and Discussion

Data from all challenges combined indicated significant acute effects for various biomarkers (Figure 3), notably a decrease in FMD (-24.7%, p=0.02), reflecting a decrease in the femoral artery’s reactivity and ability to accommodate increased blood flow during hyperemia. The observed decrease in femoral vein baseline SvO2 (-17.3%, p=0.009) could be due to an increased delivery of oxygen at the capillaries or an impaired oxygen uptake by the lungs. A decrease in femoral artery baseline velocity (-35%, p=0.002) is in line with decreased arterial reactivity following aerosol exposure. Finally, there was a significant decrease in the washout time of venous oxygen-depleted blood (-14.3%, p=0.02) and a significant increase in the overshoot (maximum SvO2 increase relative to baseline) (-27.4%, p=0.03). ANOVA yielded no significant difference between the three different challenges, likely due to small sample size of the subgroups. No significant differences were detected between the baseline biomarkers in non-smokers and smokers/vapers, possibly due to inadequate power.Conclusion

This ongoing study suggests that smoking/vaping challenges causes acute effects on several vascular biomarkers. Further recruitment of subjects will provide more insight into the differential effects of each type of challenge and allow us to investigate potential confounding effects due to age and gender in the intricate relationship between smoking/vaping and vascular function changes.Acknowledgements

NIH Grant R01 HL155243References

1. Ramamurthi D, Gall PA, Ayoub N, et al. Leading-Brand Advertisement of Quitting Smoking Benefits for E-Cigarettes. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(11):2057-2063.2. Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes: a scientific review. Circulation. 2014;129(19):1972-1986.

3. Caporale A, Langham MC, Guo W, et al. Acute Effects of Electronic Cigarette Aerosol Inhalation on Vascular Function Detected at Quantitative MRI. Radiology. 2019;293(1):97-106.

4. Langham MC, Li C, Magland JF, et al. Nontriggered MRI quantification of aortic pulse-wave velocity. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(3):750-755.

5. Langham MC, Jain V, Magland JF, et al. Time-resolved absolute velocity quantification with projections. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(6):1599-1606.

Figures

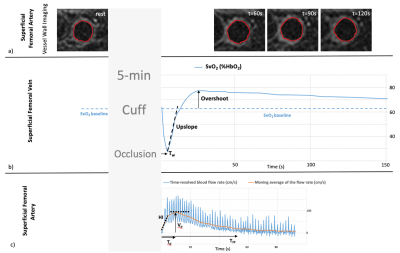

Figure 1

a) Regions of interest on the femoral artery luminal wall at baseline and at different time points after cuff release to determine the cross-sectional areas and then peak FMD.

b) Femoral vein oxygen saturation (SvO2) plotted vs time after cuff release. SvO2 is derived from the difference between venous and arterial signal phase. (Tw = washout time)

c) Average blood flow velocity-time curve in the femoral artery. (HI = hyperemic index; Vp = peak velocity; Tp = time to peak; TFF = Time of forward flow = hyperemia duration)

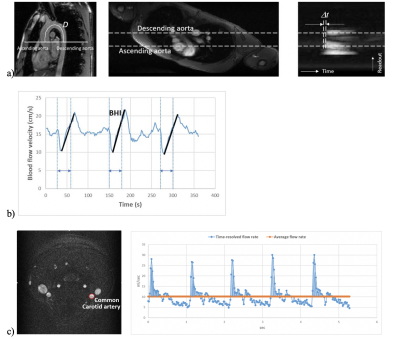

Figure 2

a) aPWV: distance D traveled by pressure wave along aortic arch; axial view of major arteries; complex difference projections showing transit time δt for wave propagation (aPWV= D/δt)

b)Breathhold (BH) challenge: BHs are indicated by double pointed arrows.

c) Axial cut at the CCA and graph representing the net arterial pulse volume (shaded area between the blue and orange lines) which is the degree of expansion of the neurovascular arterial tree during systole relative to its average volume during the 5 cardiac cycles. NVC is derived from dividing this value by pulse pressure.

Figure 3

a) Effect of smoking/vaping challenges on MRI biomarkers pre-versus post intervention (%). Data are means ± standard error followed by the sample size N in parentheses. Baseline SvO2 and CMRO2 were obtained while subject was breathing normally.

b) Box and whisker plots highlighting some of the significant effects with data pooled from all smoking/vaping interventions (blue=pre, orange=post-challenge).