1073

Joint Velocity and Acceleration Encoding for Improved Pressure Gradient Mapping in Flow Imaging1Radiological Sciences Laboratory, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Radiology, Veterans Administration Health Care System, Palo Alto, CA, United States, 3Bioengineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Flow, Velocity & Flow

In this work, we introduce an optimized motion encoding strategy for flow measurements that simultaneously and non-colinearly encodes velocity and acceleration into data phase. This enables velocity-based flow measurements and improves pressure gradient mapping derived from the acceleration data. The method is tested in a stenotic flow phantom, where the proposed method shows good velocity agreement with conventional 4D-flow methods, while also producing improved pressure gradient maps when compared to both 4D-flow and a CFD reference.Introduction

Measuring intravascular pressure gradients is a powerful tool for understanding cardiovascular pathologies. High pressure gradients often indicate more severe disease, as occurs in valvular stenosis or aortic coarctations. Catheter-based pressure gradient mapping is the clinical and research gold standard. This is, however, an invasive procedure.Phase contrast MRI (PC-MRI) has been shown capable of measuring in vivo pressure gradients1-2. Generally, this is done with velocity encoding techniques such as 4D-Flow. This technique has fairly good accuracy, but it is highly sensitive to noise in the flow data.

Previous work showed that by directly encoding acceleration instead of velocity, noise sensitivity was decreased, and therefore the accuracy of pressure gradient mapping was improved3. However, this requires an extra acceleration-encoded acquisition that extends exam times and may be clinically infeasible.

In this work, we aimed to develop and demonstrate a numerically optimal method for simultaneously encoding velocity and acceleration in an MRI acquisition for improved pressure gradient mapping while also obtaining flow measurements.

Methods

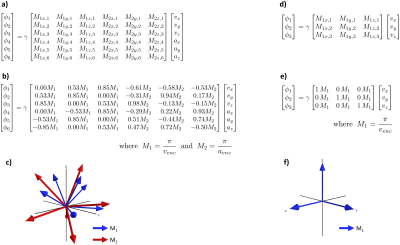

In PC-MRI, the 1st and 2nd gradient moments ($$$\vec{M}_1$$$ and $$$\vec{M}_2$$$) are directly proportional to the measured velocity and acceleration ($$$\vec{v}$$$ and $$$\vec{a}$$$), respectively. By controlling $$$\vec{M}_1$$$ or $$$\vec{M}_2$$$, we control the mapping (encoding matrix) of $$$\vec{v}$$$ or $$$\vec{a}$$$ into the complex phase of the measured data. While many strategies for flow encoding matrices exist, they all either consider $$$\vec{v}$$$ or $$$\vec{a}$$$ in isolation, assuming separate scans are needed for each. This was generally the case because designing gradients with non-colinear $$$\vec{M}_1$$$ or $$$\vec{M}_2$$$ was difficult.In this work, we design gradient waveforms with an optimization framework (GrOpt)4, which allows for the design of time optimal encoding gradients that have unique and non-colinear $$$\vec{M}_1$$$ and $$$\vec{M}_2$$$. This then enables the generation of encoding matrices that can be designed to encode both $$$\vec{v}$$$ or $$$\vec{a}$$$ simultaneously. We design an encoding matrix values by using $$$\vec{M}_1$$$ directions as in ICOSA6 encoding5, and then picking new $$$\vec{M}_2$$$ directions for each encoding to minimize condition number. Figure 1 shows this encoding matrix.

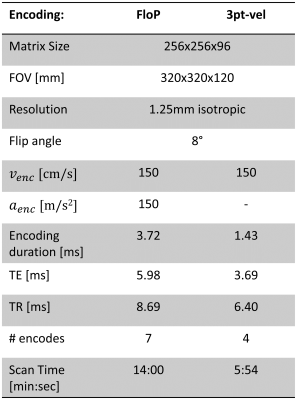

Time-optimal gradient waveforms were designed to have the required $$$\vec{M}_1$$$ and $$$\vec{M}_2$$$, while staying within the system hardware limits. Figure 2 shows the designed encoding gradients used in this work for the joint flow and pressure (“FloP”) measurements. A reference acquisition using a three-point velocity-only was also collected (3pt-vel). Scan parameters are given in Figure 3. The sequences were implemented in Pulseq6.

A flow phantom was 3D printed using a flexible material (NinjaTek Cheetah), with a main diameter of 16mm, and a 50% stenosis. A programmable flow pump (Shelly CardioFlow 5000) was used to generate a steady 140mL/s flow rate through the phantom.

Pressure gradients were calculated using the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations with the acceleration data from the FloP acquisition, and derived acceleration from the 3pt-vel acquisition. Relative pressure was calculated in 3D by directly solving for pressure with LSQR optimization from the pressure gradients7. For comparison, a CFD simulation (SimVascular8) was also performed, matching the phantom, and using the acquired velocity data as an input.

Results

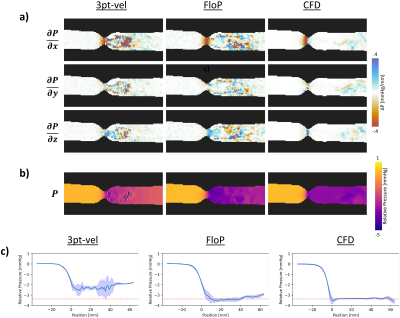

The designed encoding matrix had a condition number of 1 (ideal). Figure 4a and 4b show the acquired phase data in the stenosis phantom for the FloP scan and the 3pt-vel scan. Figure 4c and 4d show the corresponding flow components. Good qualitative agreement is seen between the velocity components; the acceleration fields look reasonable for flow through a stenosis. A comparison of flow rates at the input of the phantom measured 135mL/s (FloP) and 137mL/s (3pt-vel), compared to a programmed flow rate of 140mL/s.Figure 5a shows the pressure gradients for the FloP and 3pt-vel measurements. Qualitatively more noise is seen in the 3pt-vel scan, and better agreement is seen between the CFD data and the FloP data. Similar qualitative comparisons are apparent in the relative pressure maps in Figure 5b. Line profiles through the relative pressure map (Fig 5c) from the FloP method show better agreement with CFD and less variability compared to 3pt-vel. Peak measured pressure drops across the phantom were 2.6, 3.5, and 3.6mmHg for 3pt-vel, FloP, and CFD.

Discussion

This work introduces a motion encoding strategy that simultaneously measures velocity and acceleration. The velocity data from the acquisition remains accurate, while the addition of acceleration data allows for significantly improved pressure gradient mapping.The tradeoff for acquiring the acceleration data is an increased TE and TR, as well as a need to acquire at least seven different encodings. While the scan time of the FloP acquisition was longer when compared to a velocity only acquisition, it is shorter than the time required to acquire a separate velocity and acceleration scan, with the added benefit of being perfectly registered. Additionally, the SNR performance may be higher as every encode contains $$$\vec{v}$$$ and $$$\vec{a}$$$ data rather than half and half (though this hasn’t been tested yet). The additional encoding strength and TE may also lead to additional intravoxel dephasing, which remains a topic of future investigation.

Future work will test the method in vivo particularly in patients with stenosis, as well as comparisons to catheter-based measurements. Additionally, the TE penalty of the encoding strategy can be alleviated by balancing the encoding matrix.

Acknowledgements

NIH R01 HL131823 to DBE, NSF

DGE-1656518 to PJN

References

[1] Markl, M., Frydrychowicz, A., Kozerke, S., Hope, M. & Wieben, O. 4D flow MRI. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 36, 1015–1036 (2012).

[2] Ebbers, T., Wigström, L., Bolger, A. F., Engvall, J. & Karlsson, M. Estimation of relative cardiovascular pressures using time-resolved three-dimensional phase contrast MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 45, 872–879 (2001).

[3] Balleux-Buyens, F., Jolivet, O., Bittoun, J. & Herment, A. Velocity encoding versus acceleration encoding for pressure gradient estimation in MR haemodynamic studies. Physics in Medicine & Biology 51, 4747 (2006).

[4] Loecher, M., Middione, M. J. & Ennis, D. B. A gradient optimization toolbox for general purpose time-optimal MRI gradient waveform design. Magn Reson Med 84, 3234–3245 (2020).

[5] Zwart, N. R. & Pipe, J. G. Multidirectional high-moment encoding in phase contrast MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine 69, 1553–1563 (2013).

[6] Layton, K. J. et al. Pulseq: a rapid and hardware-independent pulse sequence prototyping framework. Magnetic resonance in medicine 77, 1544–1552 (2017).

[7] Song, S. M., Leahy, R. M., Boyd, D. P., Brundage, B. H. & Napel, S. Determining cardiac velocity fields and intraventricular pressure distribution from a sequence of ultrafast CT cardiac images. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 13, 386–397 (1994).

[8] Updegrove, A. et al. SimVascular: An Open Source Pipeline for Cardiovascular Simulation. Ann Biomed Eng 45, 525–541 (2017).

Figures

Figure 1: a) General equation for the proposed encoding matrix, where both $$$\vec{M}_1$$$ (velocity) and $$$\vec{M}_2$$$ (acceleration) are encoded. b) Optimized encoding matrix coefficients used in this work, with $$$v_{enc}$$$ = 150 cm/s and $$$v_{enc}$$$ = 150 m/s2. c) 3D depiction of the directions described in b). d-f) Encoding matrix details for the 3pt-vel acquisition ($$$v_{enc}$$$ = 150 cm/s ).

Figure 2: Optimized encoding gradient waveforms used for encoding unique and non-colinear $$$\vec{M}_1$$$ (velocity) and $$$\vec{M}_2$$$ (Fig 1b-c) in this work. Each row is a different encoding, and each column is a different gradient axis.

Figure 3: Imaging parameters. Both scans include a background phase measurement with no encoding.

Figure 4: a) and b) Measured phase from the FloP and 3pt-vel acquisitions as measured in the stenosis phantom. c) and d) Measured flow components. Good agreement is seen between the velocity data, and reasonable acceleration fields are generated.

Figure 5: a) shows the derived pressure gradients from 3pt-vel, FloP, and the CFD simulation. The FloP data appears less noisy and appears to agree better with CFD. b) shows the relative pressure maps, where the FloP data also appears less noisy and better matches the CFD data. C) shows data from a centerline through the relative pressure map. Shaded regions represent the standard deviation obtained from a 7x7 grid of lines around the centerline. The FloP data has less variability, and better agreement with CFD.