1064

A radiofrequency coil for infants and toddlers1Centre for Functional and Metabolic Mapping, Western University, London, ON, Canada, 2Department of Medical Biophysics, Western University, London, ON, Canada, 3Applied Psychology, Western University, London, ON, Canada, 4Western Institute for Neuroscience, Western University, London, ON, Canada, 5Department of Pediatrics, Western University, London, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: RF Arrays & Systems, RF Arrays & Systems

This abstract presents an adjustable RF coil designed for imaging three-month-old infants to three-year-old toddlers, where motion and variance in head size can be detrimental to image quality. The coil is designed with an open face to allow for the use of camera or motion tracking systems. The tailored RF coil produced higher SNR and lower geometry factors than adult coils. Accelerated protocols can now be combined with prospective motion correction, thereby improving the success rate of imaging infant and toddler populations.

Introduction

Infants and toddlers are a challenging population on which to perform MRI of the brain, both in research and clinical settings. Due to the large range in head size during the early years of development, paediatric neuro-MRI requires an RF coil1, or a set of coils2,3, that is tailored to head size to provide the highest image quality. Size-adaptable coils4–6 have the added benefit of creating a tight fit over a range of head sizes, thereby commensurately mitigating subject motion. This abstract, modelled after the earlier work by Ghotra et al.5, describes an RF coil with a tailored mechanical-electrical design that can adapt to the head size of three-month-old infants to three-year-old toddlers. The coil is designed without visual obstruction to facilitate an unimpeded view of the child’s face and the potential application of camera or motion-tracking systems7–11.Methods

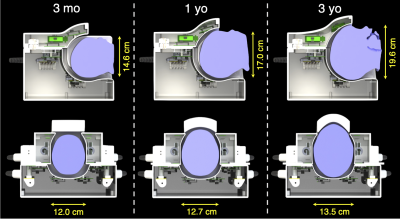

The coil housing was designed to accommodate children between the ages of three months and three years, based off the average head shape of a 3-year old12,13. The coil was split into four sections to adapt to the variability in head size (Figure 1). The posterior section was stationary, while the left and right sections could slide laterally to create a housing width between 12.0 – 17.1 cm. This served two purposes: (i) to increase coil sensitivity by ensuring the closest possible proximity to the brain and (ii) to mitigate head motion. This adaptive topology was based off the design presented by Ghotra et al.5 for infants aged 1 – 18 months; however, the older and wider age range desired for this study necessitated design modifications to accommodate a larger variance in the anterior-posterior dimension of the head. This variance was addressed by constructing three interchangeable anterior sections based off the average head sizes of a three-month old, one-year old, and three-year old12,13 (Figure 2). No coil elements or mechanical structure were placed in front of the subject’s face to accommodate the use of a camera or motion-tracking system. All CAD drawings have been made openly available: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/6EZ4Q to add this solution to the collection of publicly available paediatric coil designs.Coil performance was compared to two vendor-supplied commercial coils intended for adult imaging: (i) a 20-channel head and neck coil and (ii) a 32-channel head-only coil. Performance metrics were acquired of a phantom that approximated the size of a 2-year-old’s head—the largest anterior section was required to accommodate this head phantom.

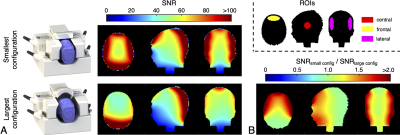

To assess the benefits of having adjustable lateral sections and multiple anterior sections, the SNR was measured of a phantom that approximated the head size of a 3-month-old. The SNR was compared when the coil was placed in its largest versus smallest configuration.

Results

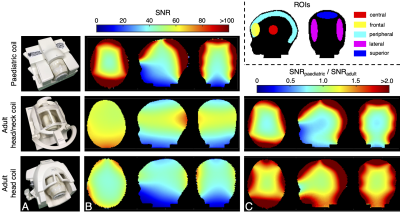

The mean and maximum noise correlation was 9.5% and 59%, respectively. In contrast, the adult head/neck and head-only coils had higher mean noise correlations (17% and 25%, respectively) due to being insufficiently loaded by the “two-year-old” phantom.The paediatric coil produced higher SNR throughout most of the brain relative to the adult coils (Figure 3) (periphery: >2-fold; superior, frontal, and lateral regions: 1.14 – 1.98-fold). In the paediatric coil, no coil elements were placed in front of the face to allow a motion-tracking camera to view the entire face; however, this also resulted in lower SNR in the centre of the brain (0.73-fold). In contrast, when compared to the adult head coil—which has fewer receive elements above the face—the paediatric coil showed a 1.04-fold SNR improvement in the central region.

The SNR of a “3-month-old” head phantom when the coil was in its tightest configuration versus when in its largest configuration showed a 1.71-fold increase in the frontal region, 1.69-fold increase in the lateral regions, and a 1.15-fold increase in the centre of the head (Figure 4). Negligible differences occurred in the posterior region of the coil.

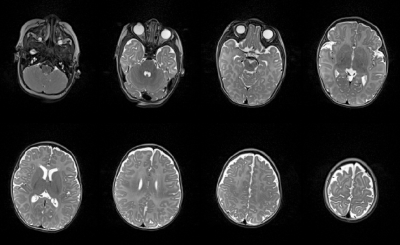

Figure 5 provides an example of the attainable image quality when scanning a three-month-old infant.

Discussion

Despite having no elements or housing in front of the face, the paediatric coil produced superior SNR throughout most of the head compared to two vendor-provided adult coils—this can be primarily attributed to the smaller coil elements and the proximity of these coils to the head through an adjustable design.Scans of the "3-month-old" head phantom in the coil’s tightest configuration produced a substantial improvement in SNR in the frontal region and lateral regions compared to scanning in the coil’s largest configuration. This demonstrates the importance of being able to vary the coil size in both the left-right and anterior-posterior dimensions over the 3-month (infant) to 3-year (toddler) age range.

The paediatric coil produced superior geometry factors compared to the adult coils, despite the open-face design. When combined with higher SNR, the result is the ability to employ higher acceleration rates to reduce scan time, thus reducing the probability of motion occurring during the acquisition. Modification to the acquisition protocol, with immobilization of the head through the adjustable coil geometry, and subsequently combined with a motion tracking system produces a compelling platform for scanning paediatric populations without sedation and with improved image quality.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Peter Zeman for fabrication assistance. This work was supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation; Canada First Research Excellence Fund to BrainsCAN; Brain Canada Platform Support Grant; the Molly Towell Perinatal Research Foundation.References

1. Hughes EJ, Winchman T, Padormo F, et al. A dedicated neonatal brain imaging system. Magn Reson Med. 2017;78(2):794-804.

2. Keil B, Alagappan V, Mareyam A, et al. Size-optimized 32-channel brain arrays for 3 T pediatric imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66(6):1777-1787.

3. Mareyam A, Xu D, Polimeni JR, et al. Brain arrays for neonatal and premature neonatal imaging at 3T. In: Proceedings of the 21st Annual Meeting of ISMRM. Salt Lake City, Utah, USA; 2013:4386.

4. Lopez Rios N, Foias A, Lodygensky G, Dehaes M, Cohen-Adad J. Size-adaptable 13-channel receive array for brain MRI in human neonates at 3 T. NMR Biomed. 2018;31(8):e3944.

5. Ghotra A, Kosakowski HL, Takahashi A, et al. A size-adaptive 32-channel array coil for awake infant neuroimaging at 3 Tesla MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2021;86(3):1773-1785.

6. Banerjee M, Follante CK, Zemskov A, et al. Optimized Pediatric Suite with head array adjustable for patients 0-5 yrs of age. In: Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Meeting of ISMRM. Milan, Italy; 2014:1768.

7. van der Kouwe AJW, Benner T, Dale AM. Real-time rigid body motion correction and shimming using cloverleaf navigators. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56(5):1019-1032.

8. Zaitsev M, Dold C, Sakas G, Hennig J, Speck O. Magnetic resonance imaging of freely moving objects: prospective real-time motion correction using an external optical motion tracking system. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):1038-1050.

9. Slipsager JM, Ellegaard AH, Glimberg SL, et al. Markerless motion tracking and correction for PET, MRI, and simultaneous PET/MRI. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0215524.

10. Frost R, Wighton P, Karahanoğlu FI, et al. Markerless high-frequency prospective motion correction for neuroanatomical MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2019;82(1):126-144.

11. Slipsager JM, Glimberg SL, Højgaard L, et al. Comparison of prospective and retrospective motion correction in 3D-encoded neuroanatomical MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2022;87(2):629-645.

12. Richards JE, Sanchez C, Phillips-Meek M, Xie W. A database of age-appropriate average MRI templates. Neuroimage. 2016;124(Pt B):1254-1259.

13. Richards JE, Xie W. Brains for all the ages: structural neurodevelopment in infants and children from a life-span perspective. Adv Child Dev Behav. 2015;48:1-52.

Figures

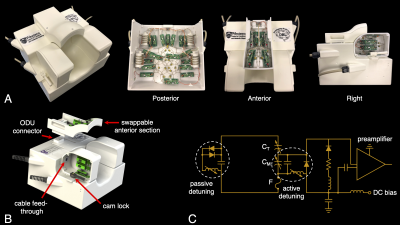

Figure 1 | (a) Photographs of the 32-channel paediatric coil. (b) Lateral sections slide laterally to accommodate varying head width. Three interchangeable anterior sections were constructed to accommodate the large range in head size over the desired age range. High-density connectors connected cables from the anterior to posterior sections. (c) A circuit schematic of a single receive element, with coil elements connected directly to low-input-impedance preamplifiers.

Figure 2 | Sagittal and axial cross-sections of the three coil configurations: for children less than three months of age, between three months and one year of age, and between one and three years of age. Representative heads approximate the average size of a three-month old, one-year old, and three-year old, with dimensions provided along the anterior-posterior and left-right directions. The adjustability of the lateral and anterior sections allows for consistent loading across the age range.

Figure 3 | (a) Photographs of the “two-year-old” head phantom within the respective coils depicts the realistic positioning of a two-year-old subject. (b) Image SNR of the head phantom, as acquired with the paediatric coil, adult head/neck coil, and adult head-only coils, shows spatially varying SNR, mainly attributable to the difference in coil size. (c) The resultant ratio between image SNR attained with the paediatric coil versus the adult coils demonstrates large increases in the periphery.

Figure 4 | (a) SNR of a “three-month-old” head phantom when in the smallest coil configuration and when in the largest coil configuration. (b) The SNR ratio between the two configurations shows a 1.71-fold increase in the frontal region, 1.69-fold increase in the lateral regions, and 1.15-fold increase in the central region when employing the tightest coil configuration. The inset provides the ROIs over which SNR ratios were calculated.

Figure 5 | Representative axial slices of a turbo-spin-echo image acquired of a three-month-old infant when in the smallest coil configuration. Matrix size: 192 x 156, field of view: 192 x 156 mm, number of slices: 115, slice thickness: 1 mm, TE/TR: 140/6150 ms, refocusing flip angle: 120°, echo-train length: 19, bandwidth: 190 Hz/pixel, acquisition time: 2 min 33 s.